Most Americans live in nuclear families, which consist of parent(s) and unmarried children, or simply two adults related by marriage or equivalent partnership. At the same time, most Americans recognize other family members outside their nuclear families. They may be grandparents, uncles and aunts, married siblings, cousins, nephews and nieces, married children, grandchildren, or in-laws. Any family member outside one’s nuclear family is called an extended family member.

Yet some Americans, often racial/ethnic minority members, share their households with extended family members. These households are called extended family households. When we examine extended family, therefore, we have to distinguish between extended family members (kins) and extended family households.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

While whether or not one lives with extended family members in the same household is a structural question, we also have to examine the nature of the interaction between extended family members. They may help each other in everyday chores, economic aspects, and psychological well-being. Conversely, they may be a source of stress, due to personality conflict, economic burden, or inheritance issues. Therefore, we need to discuss interactional/functional aspects of extended family as well.

I will examine functional/interactional issues of the extended family first, followed by structural issues.

Extended Family Members Outside The Household

Extended family members may get together for holidays or weddings, but otherwise, each nuclear family is quite isolated in everyday life; that’s what social scientists believed. When data were first collected from American families several decades ago, however, the results were surprising. Most Americans are in close contact with extended kin, particularly their elderly parents. One research study indicates that as many as 78% of elderly people who do not live with any of their children saw at least one of them in the past week. The proportion was similar in other industrialized countries such as Denmark and Great Britain.

Extended kin also get together for holidays, birthdays, vacations, weddings, and funerals. Even if extended kin live far away, contacts are often made through phone calls, e-mails, and/or letters. In other words, in fully industrialized societies where most people live in nuclear family households, extended kinship network is alive and well. This kinship network is often called modified extended family structure.

This modified extended family structure exists in contemporary societies because it serves certain functions. Although each household is supposed to be, and usually is, a self-sufficient unit, it is often necessary to exchange help with extended kin who do not live in the same household.

This support may be economic. Relatively well-to do parents may rent their residential property for a less-than-market value to their married children. An adult child may financially support his or her elderly parents who are in a nursing home. Retired parents often assist their adult children with child care, free of charge. Adult children may help their parents in everyday chores, personal cares, or transportations, all of which may be substituted by hired services.

Emotional functions provided by extended kin are important as well. Checking up on each other through visits and phone calls provides emotional support, particularly in times of hardship such as illness, death of a family member, family problems, or economic downturn. Even without any hardship, regular contacts by extended kins including visits, phone calls, e-mails, and letters often help stabilize one’s emotions.

Modified extended family structure is alive and well because of these functions it provides.

Dealing with extended kins, however, is not always a pleasant experience. Elderly parents may want to interfere with how the children are raised. An adult sibling may keep asking for economic assistance. Married children may cause constant heartaches by getting into trouble with drugs. Friction with in-laws is a well-known source of tension.

Like it or not, we feel a certain degree of obligation to deal with our extended kins. This sense of obligation differs from one individual to another, within each family, and within one’s ethnic/racial group. We will revisit this point. In the next section, I will examine structural aspects of extended family, more specifically, extended family households.

Extended Family Households

Approximately 10% to 15% of family households in the United States are extended family households. This percentage, however, is for a particular time period (called cross-sectional data). If you ask, “Have you ever lived in an extended family household?” the proportion would be much higher. This is because each household expands and contracts depending on demographic phenomena such as marriage, birth, and death.

The same is true for historical data on extended family households. While many societies held extended family household as a normative (i.e., desirable) household type, this does not necessarily assure its prevalence. People simply did not live long enough to see their children marry to someone and have their own offspring. Even when someone survived long enough to live with his or her child-in-law or grandchildren, the life span of this extended family household was usually short, so that it may not be recorded in family registry records, etc., making the proportion of extended family households appear smaller.

Thus, whether or not extended family households are formed depends on the demographic force involving that particular household. As is discussed below, extended family household formation also depends on the cultural and economic forces surrounding the household.

Racial And Ethnic Variation: Culture Or Economy

Early sociologists argued that nuclear family households are better suited in industrialized societies. To they can live independently or not (filial responsibility). A typical family norm states that the oldest son lives with his parents for his entire life, taking care of them if or when they become frail or sick.

Figure 1 Distribution of Household Types for Each Racial/Ethnic Group

Figure 1 Distribution of Household Types for Each Racial/Ethnic Group

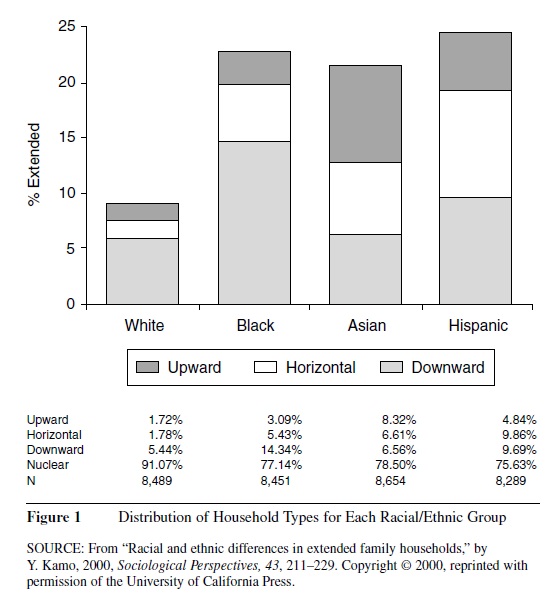

We have another interesting example of the cultural effect on extended family households in the United States among racial/ethnic minorities. It is natural to expect that Asian immigrants in the United States carried the social norm of their home country regarding family relationship and filial responsibility with them. A recent research study based on 1990 U.S. Census data tells us that Asian immigrants and their offspring are more than twice as likely to live in extended family households than non-HispanicWhite Americans (22% vs. 9%; see Figure 1). More specifically, their typical extended family household is composed of the head of household, his wife and children, and his parents. Since this type of household extends live competitively in industrialized societies one often has to move to wherever the new job is located. Extended family households are ill-suited for this, they argued. In many industrialized countries in Asia (i.e., Japan, Korea, and Taiwan), however, there still are many extended family households.

The prevalence of extended family households in certain countries is in part attributed to prolonging life expectancy. The female life expectancy in Japan in 2001 was, for example, 84.93 years, compared with 43.20 years in 1921–1925 (for 5 years combined). A society that has more elderly people is more likely to have a larger proportion of extended family households.

Nevertheless, this demographic force is only part of the story. The prevalence of extended family households in some countries is mostly due to their cultural factors or social norms. Most Asian countries share a Chinese tradition of Confucianism, which emphasizes respecting the elderly and taking good care of elderly parents whether upward from the head of the household, we call this upwardly extended family household. Since Asian Americans do not have much longer life expectancy or smaller average income than their non-Hispanic White counterparts, we cannot attribute this racial difference to demographic or economic forces. It is found that those Asians born in the United States are less likely to live in extended family households than those who were born in their home country. This indicates that the cultural force is at least partly responsible for this ethnic uniqueness.

When you examine two other racial/ethnic groups, Hispanic Americans and African Americans, an interesting pattern emerges. First of all, the percentages of extended family households are much higher among both minority groups than among non-Hispanic Whites: 24% among Hispanic Americans and 23% among African Americans, compared with 9% among nonHispanic Whites (Figure 1).

More specifically, however, extended family households among African Americans are most likely to be downwardly extended (head of household lives with a child-in-law or grandchildren) and those among Hispanic Americans horizontally extended (head of household lives with siblings). This is in contrast to Asian Americans. Similar to Asians’ filial responsibility, Mexicans have been long known to honor the idea of “familism,” which places priority on the entire family’s welfare over individual members’ benefits. This cultural norm is undoubtedly related to the prevalence of extended family households. Those who have come to the United States are typically young and haven’t established their own households. When they depend on their previously immigrated siblings in residence, we see the formation of a horizontally extended household.

African Americans are also known to have a strong intergenerational tie, often through the maternal line. When a daughter marries or becomes a mother early, she often depends on her parents by living with them, forming a downwardly extended family household. Difficult economic circumstances among young African Americans and a strong intergenerational tie both make this pattern prevalent among them.

Extended family can be examined upon either its functional/interactional significance or its structural characteristics. For the latter, we pay attention not only to demographic but also economic and cultural factors surrounding that particular family, as shown in racial/ethnic variations in the United States.

References:

- Kamo, Y. (2000). Racial and ethnic differences in extended family households. Sociological Perspectives, 4, 211–229.

- Kamo, Y., & Zhou, (1994). Living arrangements of elderly Chinese and Japanese in the United States. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56, 544–558.

- Kokuritsu Shakai Hosho Jinko Mondai Kenkyujyo [National Institute of Population and Social Security Research]. (2003). Jinko Tokei Shiryo-shu. Tokyo: Author.

- Parsons, T., & Bales, F. (1955). Family, socialization and interaction process. New York: The Free Press.

- Shanas, E. (1973). Family-kin networks and aging in cross-cultural perspectiv Journal of Marriage and the Family, 35, 505–511.