Historically, African Americans have been studied and explained as compared with the values and characteristics of Europeans. The term African American is an Afrocentric word adopted as a label for people who live in the United States and are descendants of slaves and who share the legacy of bondage, segregation, and legal discrimination. Their ancestors came from sub-Saharan Africa. The Afrocentric view holds that African Americans (people of African descent, African people) and their interests must be viewed as actors and agents in human history, rather than as marginal to the European historical experience.

The second Africans in North America (1528) came as indentured servants or as part of a ship’s crew; the second wave of immigrants were captured in Africa and sold into bondage for the slave trade in the United States. Some of these individuals lived as free men and women, and others earned their freedom. By 1600, most African Americans were forced to come to this country as slaves on ships and under the most extreme and horrid conditions; many perished in the journey. The forced migration of people from subSaharan Africa occurred as a result of the growth of the tobacco and cotton industries and a need for a free and renewable labor force. Africa became a major source of the labor force that made the United States prosperous. Slavery remained legal for 200 years. About 500,000 Africans were forced into slavery in the United States; legalized slave trading was abolished in 1808.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Before the 19th century, other terms were commonly used to refer to African Americans, including words such as “colored,” “Negro,” and “black.” The term “colored” was used during the 1800s as a means of including individuals who were the product of miscegenation (children who were born of parents who were either of European/white, American/Native American or a combination of both, and African/ black). Other terms were used simultaneously during the 1890 census (e.g., black, mulatto, quadroon and octoroon, depending upon the degree of white blood in their ancestry).

The political correctness of what to call African descendants changed again during the 20th century. As a result of the Civil Rights movement of the 1970s, African Americans demanded that they be referred to as “Negro” versus “colored.” During the 1970s, the Black Power movement brought about the term “black” as the appropriate reference term, followed by the term African American in the 1990s. Forms used during the 2000 Census allowed citizens to selfidentify as African American/black, making the terms interchangeable. By 2003, almost half of blacks preferred to be called African American.

The label African American remains a controversial and ambiguous term for several reasons. First, not all people of African descent were descendants of slaves born in the United States. Changes in the federal immigration law in the 1960s resulted in an influx of people from sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. These people were descendants of Africans but were not born in the United States and did not share the legacy of slavery. Their presence caused a major demographic shift in the African American population. During the 1990s, the numbers of immigrants to the United States from Africa nearly tripled; the number from the Caribbean grew by more than 60%. The number of foreign-born people of African descent was estimated to be 2.0 million in 1999, and this number represents 8% of the foreign-born population in the United States. Additionally, individuals of African descent who continue to reside in their native countries (Caribbean, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, South America, and Canada) are also African Americans because of their ancestors and the fact that they reside in the Americas; none of these individuals considers himself or herself as African American, nor do governmental officials. For instance, individuals of mixed ethnicities of African and Hispanic descent are labeled on census forms as Hispanic. Others are separated as being black of Hispanic origin. Another example is people from Haiti who consider themselves Haitian, not African Americans. These individuals are classified as African American/black, resulting in a 14% (more than 4.4 million) increase in the population of African Americans, whereas the total U.S. population grew by only 10%.

Second, not all people of sub-Saharan African descent are “black.” One interesting issue came to light during the 2004 presidential campaign. Historically, individuals who come from the continent of Africa are automatically thought to be black. However, a number of individuals of Euro-Caucasian and Asian-Indian descent had children who were born African. When these individuals grow up and immigrate to America, they too are technically African Americans. The same label also applies to black Africans who immigrate to the United States.

Third, the commonly identified ways of recognizing African Americans involve skin color, hair texture, and facial features. Not all African Americans have dark skin, kinky hair, broad noses, or thick lips. These characteristics often exist in other racial groups and ethnicities. There are many examples of people who self-identify as African Americans who fit the stereotypical physical features of Europeans (pale or light skin, straight hair, long thin noses, and thin lips). Historically, in the United States, any descendant of a slave, regardless of physical features, was called colored or Negro. To maintain the slave status of African descendants, any person who had a mother who was a slave was identified as a slave. Not only does the onedrop rule apply to no other group than American blacks, but apparently the rule is unique in that it is found only in the United States and not in any other nation in the world. In fact, definitions of who is black vary quite sharply from country to country, and for this reason, people in other countries often express consternation about the American definition. The onedrop rule was done to ensure the steady supply of slave labor: 4 million slave laborers for the tobacco, cotton, and agricultural industries.

Origins Of African Americans

Most African Americans came to the United States in bondage. Although slavery is an institution as old as civilization (it has existed in some form among peoples of all ethnic groups), the industry changed radically with the introduction of Europeans into Africa in the 15th century. The first Africans captured and sold into bondage were exported to Central and South America to work in Portuguese and Spanish Colonies and on the sugar plantations of the Caribbean islands. As cotton, tobacco, and other agricultural needs in the colonies of North America increased, so did the demand for a cheap labor source; this demand was met with the importation of Africans. Unfortunately, the inhuman conditions of their transport resulted in 30% to 50% of Africans dying before they reached their destination.

The first documented African to come to this country was Estebanico (also known as Estevan, or Stephen). He arrived as a part of an expedition of 400 people from Cuba. Estevan was a slave who came to this country in February of 1528 in search of the Rio Grande River. He was killed as a part of that venture in May of 1539. The second group of Africans to arrive in North America came 100 years before the Mayflower, before what is commonly reported to be the arrival of Africans in the American colonies (Jamestown, 1619). Twenty Africans worked as indentured servants. Like other indentured servants, their servitude expired after a certain period, at which time they were freed and given a small sum of money and land to start a new life. Other Africans were also brought by Europeans: English, Dutch, French, and Spanish settlers in 1626 to New Amsterdam (later New York), and in 1636 to Salem.

As the demand for a cheap labor source grew, plantation owners found that European indentured servants and indigenous Indians were becoming scarce, and many died under the harsh working conditions. The Indian slaves, because of their knowledge of the land, were able to run away and avoid recapture. Africans represented a renewable or replaceable resource when they died and did not run away as easily because they were in a foreign land. Additionally, their physical features made them easy to identify and recapture.

Another factor that perpetuated the slave conditions of the Africans in America was the passage of laws and the acceptance of the view that they were not human beings and therefore could be treated as beasts of the field. Before 1667, most colonists believed that if a person became a Christian, he or she could not be held in slavery. The laws held that no Christians could be a slave for life; therefore, those Africans who became Christians could work their way out of slavery as indentured servants. However, in 1640, the standards for Africans were legally changed to state that only white Christians could not be enslaved for life.

In 1641, Massachusetts adopted a regulation making slavery an institution. Other colonies followed suit. That regulation held that all children born in the colonies should be defined by the race of the mother—making race an inherited condition. Religious and political philosophies were also adopted that made slavery morally correct. Slaves were defined as outsiders and were dehumanized, thus making their enslavement acceptable to the “good” Christians of the colonies. The substandard conditions of slaves were further legalized in the Declaration of Independence. The document that treasured the right to freedom of Europeans gave them the right to own slaves and pass that ownership down to their progeny; slaves could be defined as property. Slave were property that could lawfully be bred, sold, housed in conditions less than those of European settlers, maimed, and even killed. American forefathers further perpetuated these conditions in the Constitution by not outlawing slavery and by counting slaves in the Census as three fifths of a man.

In 1807, the importation of slaves from Africa and slave trade were abolished. Unfortunately, this action only created a need for slave owners to find ways of maintaining a cheap and renewable labor force to continue their prosperity. One effective method of controlling slaves was to separate them from fellow tribesmen and their families, to prohibit them from speaking their native languages, and to strip them of any identity they may have held onto from their country of origin. Traces of these attitudes toward African Americans continue to exist in contemporary American society. The legal condition of slavery ended with the end of the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation.

Equality And Freedom For African Americans

In 1954, the Supreme Court of the United States passed a momentous decision when it ruled in Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, and overturned the legalization of segregation “separate but equal” (1896, Plessy v. Ferguson), which set the stage for the 1964 Civil Rights Act. This act led to further legislated desegregation and to specifically and inclusively define all of the areas in which society must desegregate itself. This led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which mandated that African Americans be allowed to vote. The 1990 Civil Rights Bill outlawed discrimination in the workplace. However, economic oppression among African Americans persists.

Demographic Characteristics

Population

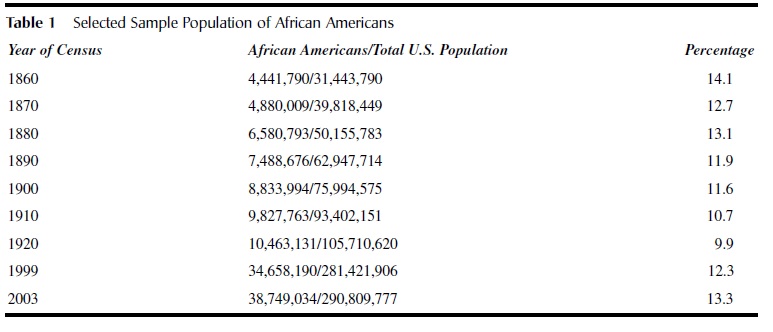

Census data for 2000 showed that non-Hispanic Euro-Americans made up 69% of the U.S. population; African Americans accounted for 12%; Hispanic Americans represented 13% (Hispanic, any race); Asian and Pacific Islanders accounted for 4%; and American Indian/Eskimo/Aleut made up 1%. The proportion of African Americans in the U.S. population has remained relatively stable since 1860, about 11% to 12% (Table 1).

Table 1 Selected Sample Population of African Americans

Table 1 Selected Sample Population of African Americans

Geographic Location

In 1870, nearly 95% of all African Americans lived in the South, and by 1960, that number had dropped to 60%. Fifty-five percent of African Americans lived in the South in 2000. Nearly 40% of all African Americans lived in suburban areas; 18% lived in the Northeast, 18% in the Midwest, and 9% in the West. In comparison, 33% of non-Hispanic Euro-Americans lived in the South, 27% in the Midwest, 21% in the Northeast, and 19% in the West.

Like the rest of Americans, African Americans primarily live in large metropolitan areas; however, unlike non-Hispanic Euro-Americans, African Americans live in the central cities of those areas.

Age Distribution

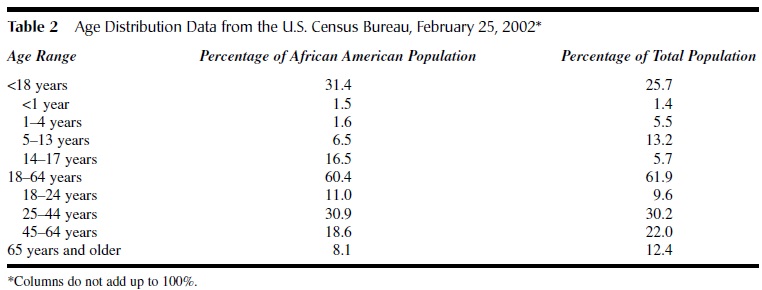

The age distribution of African Americans in the United States is skewed toward individuals over the age of 25 (Table 2). Most African Americans are older than 18 years but younger than 64 years; the largest group within this category is between the ages of 25 and 44 years. The next largest group of individuals is between the ages of 45 and 64 years, followed by youth between the ages of 14 and 17 years.

Education

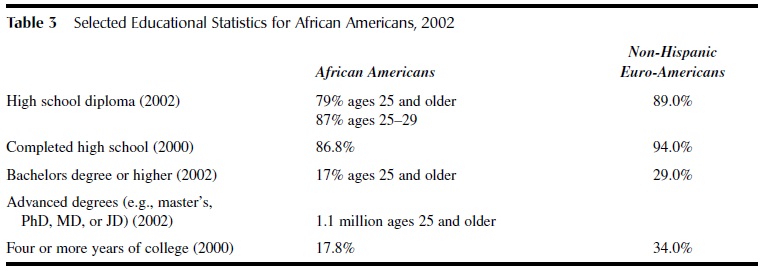

Most African Americans ages 25 and older in 2002 had obtained a high school diploma (Table 3); 17% had earned a bachelor’s degree, and 17.8% had 4 years or more of college. Unfortunately, the rate of graduation in 2002 for this population had dropped by 7.8%. Additionally, rates still are lower than for nonHispanic Euro-Americans.

Income

In 1950, African Americans averaged only 54% of the income of Euro-Americans. That average is currently at 55%. In 2002, the median annual income for African Americans was $29,177, which was 62% of Euro-American families’ income. Young African American males, at all educational levels, continue to experience unemployment rates (1999) more than twice those of young Euro-American males.

Employment

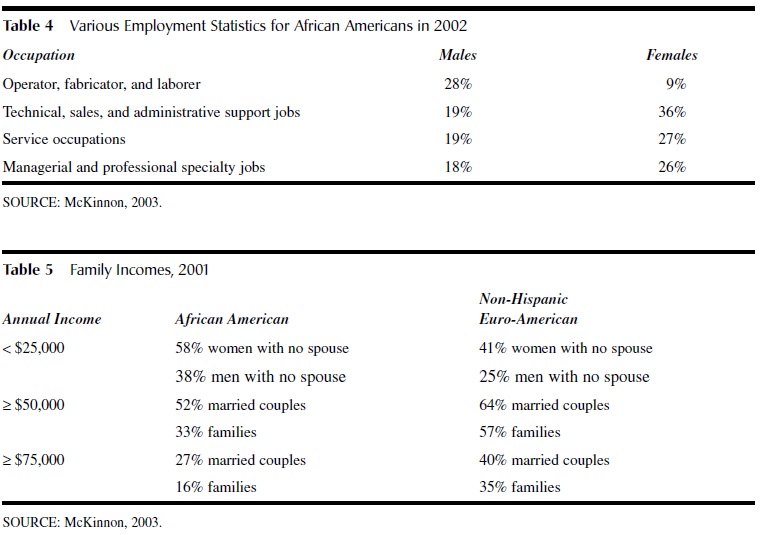

In 2002, slightly more than one fourth of African Americans were employed laborers, whereas equal numbers were employed in white collar jobs (Table 4); most individuals were employed in white collar jobs (56%). African American females continue to have more employment opportunities than African American males.

Of the 74.3 million families with money income in 2001, 8.8 million were African American, and 53.6 million were non-Hispanic Euro-Americans (Table 5).

Table 2 Age Distribution Data from the U.S. Census Bureau, February 25, 2002*

Table 2 Age Distribution Data from the U.S. Census Bureau, February 25, 2002*

Table 3 Selected Educational Statistics for African Americans, 2002

Table 3 Selected Educational Statistics for African Americans, 2002

Poverty

In 2001, 6.8 million families in the United States had incomes below the poverty level. Of these families, 1.8 million were African American and 3.1 million were non-Hispanic Euro-American. However, a greater percentage of African American families than of non-Hispanic Euro-American families were poor: 21% compared with 6%. A larger proportion of African American married-couple families (8%) than of non-Hispanic Euro-American families (3%) were poor. Families with one parent as head of household and especially those maintained by women with no spouse present have higher poverty rates overall. These rates are highest for African American heads of household. About 30.2% of all black children younger than 18 years lived in poverty in 2001.

Family Characteristics

The common view of African American families is that they are poor, are inferior to Euro-American families, represent a monolithic institution, live in urban areas, and are wrought with pathology. More contemporary Afrocentric views offer that the nuclear family is very functional rather than dysfunctional, that is, not pathological (abnormal) in terms of African heritage and kinship networks. The cultural differences that exist between African American and Euro-American families are based on the African Americans’ African heritage combined with the reality of racial oppression, past and present. Previous studies of African American families did not respect African American culture, included interviews of African American fathers, and only focused on the very poorest families. Subsequent findings were then erroneously generalized to all African American families. Finally, researchers used theoretical models limited to Western cultural lifestyles.

For instance, in the European view, fathers should be head of household; therefore, the stereotypes of African American families as matriarchal led them to attribute pathology to this culture. However, recent research supports that African American families at all socioeconomic levels are equalitarian, characterized by complementarity and flexibility in family roles, in contrast to the normative pattern of white families with the more traditional patriarchal authority structure. These families are strong and tend to encourage their children to develop the skills, abilities, and behaviors necessary to survive as competent adults in a racially oppressive society. In general, black families are reported to be strong, functional, and flexible. They provide a home environment that is culturally different from that of Euro-American families in a number of ways.

The numbers of babies born to unmarried African American mothers is almost two times that of EuroAmericans, and the number of single parents and divorces is also higher for this group but is reflective of national trends.

Culture

The Human Genome Project made the issue of race moot. Researchers found that humans were more than 99% the same regardless of physical characteristics. The variation that is observed is not significant enough to warrant racial labels. Therefore, African Americans simply represent ethnic group variations. Those anthropological and biological differences that result in physical trait differences between groups are frequently found in the range of variation within each group. For instance, there are African Americans who have fair skin, blue eyes, and blond hair; conversely, there are Euro-Americans who have dark skin, brown eyes, and dark, kinky hair.

African Americans represent the only Americans whose initial migration was a forced migration. They represent an incredibly wide-ranging and diverse group of people. The cultural aspects of African American life represent a combination of all ethnic groups in the Americas. What sets African Americans apart is how they have retained vestiges of their African heritage while incorporating aspects of Latin, European, Middle Eastern, Asian, and Native American cultures to create music, art, food, clothing, and linguistic styles that have influenced people from around the world. Contemporary examples include the influences of African American Rap music and Jazz on popular Euro-American culture. These influences can be seen in other countries around the world.

When Africans were forbidden to use their native languages and to communicate with people who looked like them but did not share their language, they created distinctive patterns of language. They also displayed ingenuity in incorporating the misspoken language of English when used by Italians, Irishmen, Native Americans, and others with whom they were forced to interact. The development of shortened forms of words and grammatical structures (pidgins) was another excellent example of the adaptability and intellect of the descendants of African immigrants. These adaptations can still be observed in the language of many people, including the Gullah on the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia, and as a part of African American Vernacular English (AAVE), black English, or Ebonics. The usage of this type of English is often considered a legitimate form of a dialect of English spoken by some African Americans.

Although certain foods are historically said to be associated with the African American culture, a review of the conditions of poor people of all ethnic groups will show that they also used many of the same agricultural products in very similar manners, and the differences are often regional as opposed to ethnic. Foods and agricultural products commonly associated with African American culture include yams, peanuts, rice, okra, grits, indigo dyes, ham hocks, pig intestines (chitterlings), fried chicken, boiled greens, gumbo, “hoppin’ John” (blackeyed peas and rice), and cotton. What does stand out is how creative Africans and their descendants became in making use of the products they found in their new land. Because they were often forced to use foods thought undesirable and discarded by their slave owners, their tenacious nature prevailed. The make-do foods were lovingly prepared and became known as soul food. Such foods are now recognized and labeled as cuisine.

Religion

African Americans come from people who embraced spiritualism; that basic belief system was transformed in the New World to Christianity for most individuals. Christianity was used as a means to help quell the unhappiness of slaves and the guilt of slave owners. Slaves were told they would receive their reward in heaven and that the protestant ethics of hard work and suffering were valued. Although EuroAmericans promoted Christianity for slaves, they kept their worship separate. This is still seen in religion today. Sunday Morning worship time has often been referred to as the most segregated time in America. Even in the time of slavery, African American churches were the seat of religious, social, and political leadership and change. The first nationwide church for African Americans was established in 1816 by Richard Allen in Philadelphia and was called the African Methodist Episcopal Church. This was followed by Baptists founding the National Baptist Convention in 1895. This is currently the largest African American religious denomination. Other religions have significant representation among African Americans. The most prominent Black Muslims organization in the United States was founded in 1935.

Holidays And Special Celebrations

African Americans and other ethnic groups have worked tirelessly to gain legal recognition of African Americans in this country. Successful ventures include the Black History Month (first recognized as Negro History Week in 1926 and extended to become Black History Month in 1976). A national holiday was enacted in 1983 by the U.S. Congress to honor slain civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., which is observed in January, the month of Dr. King’s birthday. African Americans also embrace most American holidays and celebration. They also recognize such holidays and celebrations connected to their other ethnic and religious heritages. A more recent recognition of African American culture is the 1966 advent of the festival of Kwanzaa. This celebration was designed to affirm the African heritage of African Americans and is celebrated December 26 through January 1. Each of these celebrations carries on the tradition of adaptation, flexibility, and inclusion as consistently demonstrated by the African descendants. The purpose of each celebration is to affirm the African heritage of its people and their struggles and triumphs.

Conclusion

The contributions of African Americans to the American culture are too numerous to cite in this article. Readers are directed to resources below to identify the scientific, cultural, religious, sports, musical, media, and other contributions of the African Americans.

References:

- African American time line 1852–1925, http://www.africancom/Timeline.htm

- African Americans by the numbers, http://www.africanameri-com/AADemographics.htm

- Bennett, , Jr. (1975). The shaping of black America: The struggles and triumphs of African-Americans, 1619–1900s. Chicago: Johnson.

- Bennett, , Jr. (1988). Before the Mayflower: A history of black America (6th ed.). Chicago: Johnson.

- Bryan, (2003). Fighting for respect: African-American soldiers in WWI military history. Retrieved from http:// www.militaryhistoryonline.com/wwi/articles/fighting forrespect.aspx

- Census Bureau facts pertaining to African Americans, http://www.africanamericans.com/CensusBureauFhtm Gates, H. L., Jr. (1994). Colored people: A memoir. New York: Random House.

- McKinnon, J. (2003). The Black population in the United States: March 2002 (Current Population Reports, Series P20-541). Washington, DC: S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/p20-541.pdf

- MSN (2004). African Americans. Retrieved from http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761587467_2/African Americans.html#endads

- Rose, P. (Ed.). (1970). Slavery and its aftermath: Americans from Africa. Chicago: Aldine.

- Taylor, L. (2002). Black American families. In R. L. Taylor (Ed.), Minority families in the United States: A multicultural perspective (3rd ed., pp. 20–47). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Retrieved from http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~rturley/Black%20Families.pdf

- S. Census Bureau, Population Division. (2004). Table 5: Annual estimates of the population by race alone or in combination and Hispanic or Latino origin for the United States and States: July 1, 2003 (SC-EST2003–05). Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/popest/states/asrh/SC-EST2003-04.html

- S. Department of Defense. (1985). Black Americans in defense of our nation. Retrieved from http://unx1.shsu.edu/~ his_ncp/AfrAmer.html

- Where in Africa did African Americans originate?, http://www.africanamericans.com/Origins.htm