Social development, a multifaceted journey, encompasses the transformations in an individual’s comprehension of, attitudes towards, and interactions with others across their lifespan. This intricate process is orchestrated by a symphony of factors, including socialization, physical maturation, and cognitive growth. Yet, it is essential to recognize that socialization is not a one-way street, but a dynamic, bidirectional influence. In this intricate dance, both individuals and society shape and are shaped by the interactions.

The genesis of social development can be traced to the earliest relationships, especially those with parents or caregivers. These initial connections serve as foundational templates, laying the groundwork for how infants and children perceive and engage with others throughout their lives. These early bonds are not just about how parents influence children but also about how children impact their parents’ development. Thus, the web of human relationships extends its threads across generations.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Throughout the expansive canvas of life, various relationships come to the forefront, each playing a unique and pivotal role in social development. Parents, siblings, peers, and romantic partners all contribute to the intricate tapestry of an individual’s social growth. These relationships, interwoven with the fabric of one’s existence, influence the development of social skills, emotional regulation, and a sense of belonging.

However, the intricacies of social development do not exist in isolation. They are deeply embedded within the larger context of society and culture. The tapestry of human interaction is imbued with the rich hues of cultural, ethnic, and religious diversity. These cultural elements shape the norms, values, and practices that guide how individuals relate to one another. Consequently, children’s development is profoundly influenced by the cultural and societal landscapes in which they are nurtured.

Furthermore, individual characteristics such as gender and socioeconomic status (SES) paint unique strokes on this canvas of social development. Gender not only influences how individuals perceive themselves and others but also how society responds to them. Likewise, SES, reflecting economic and social standing, casts a shadow that affects attitudes, behaviors, and interactions with peers and society.

In essence, social development is an intricate interplay of individual growth, relationships, and the broader social and cultural milieu. It is a dynamic journey, marked by bidirectional influences, cultural nuances, and the profound impact of early relationships. As experts in psychology, we explore the depths of these complexities, seeking to unravel the mysteries of how individuals grow, interact, and thrive within the ever-evolving tapestry of human society.

Initial Relationships

In the intricate tapestry of human development, the concept of attachment, as illuminated by the pioneering ethologist John Bowlby, emerges as a profound cornerstone. Bowlby’s theory posits that infants forge reciprocal attachments with their primary caregivers, a profound interconnection where both parties become emotionally bonded. These attachments, far from arbitrary, serve as evolutionary bedrocks, enhancing the likelihood that caregivers will provide protection and nurture to the vulnerable infants.

These early attachments, like masterpieces in the making, gradually unfold over time as infants and caregivers refine their abilities to decipher and respond to each other’s cues. By around seven months of age, infants typically establish clear-cut attachments to their familiar caregivers, an emotional tether that offers them a secure base from which to explore the world around them. With caregivers as their steadfast anchors, infants exhibit a remarkable willingness to venture into the unknown, their exploratory spirit buoyed by the presence of their trusted protectors.

Attachments do more than provide emotional support; they also serve as a compass, guiding a child’s navigation through the intricate terrain of social relationships. Bowlby proposed that infants, in their formative years, develop a blueprint, an initial working model, if you will, of their caregivers. This blueprint, a sum of their caregivers’ responses to their distress, informs their expectations about social relationships throughout their lives, rippling through childhood, adolescence, and into adulthood.

For those fortunate to have warm, nurturing relationships with their caregivers, this blueprint lays the foundation for a future filled with the expectation of positive, fulfilling relationships. However, for those whose early relationships were marred by negativity, the blueprint may cast a shadow, leading to guardedness and defensiveness in future interactions, anticipating hurt rather than warmth.

In essence, the bonds formed in infancy echo across the years, sculpting the contours of future relationships. Bowlby’s insights into attachment illuminate the profound interconnectedness of early experiences, expectations, and the trajectories of social development. As experts in psychology, we delve into the depths of these intricate connections, seeking to understand how these early threads weave the fabric of individuals’ lives, shaping their encounters and bonds with others as they journey through the intricate tapestry of human existence.

In the rich tapestry of infant development, Mary Ainsworth, a contemporary of John Bowlby, wove an intricate pattern through her pioneering work on the “strange situation.” This novel assessment aimed to unravel the quality of children’s attachments to their caregivers, shedding light on the profound dynamics at play in these early relationships.

Imagine a 1-year-old child, navigating a series of potentially distressing scenarios: encounters with strangers, the unsettling departure of their caregivers, and their eventual return. From these experiences, children are classified into distinct attachment styles based on their coping mechanisms.

- Secure Attachments: Children with secure attachments may experience distress when separated from their caregiver, but they find solace and comfort upon the caregiver’s return. Their attachment provides a secure base from which they can confidently explore the world.

However, the fabric of attachment is not uniform; it bears intricate patterns of insecurity:

- Avoidant Attachment: Some children develop an avoidant attachment style. They may appear unresponsive when their caregivers are present, displaying minimal distress upon separation. Paradoxically, they may be slow to respond or actively avoid their caregivers upon their return.

- Resistant Attachment: Others gravitate towards a resistant attachment style. These children seek closeness to their caregivers but often shy away from exploring their environment. Separation triggers profound distress, and their reunions are often marked by angry, resistant behavior.

- Disorganized/Disoriented Attachment: The most heart-wrenching attachment pattern emerges in the context of abuse. Abused infants frequently display disorganized/disoriented attachment styles, marked by fear of their caregivers. They exhibit a complex mix of avoidant and resistant behaviors, mirroring their tumultuous experiences.

What weaves the fabric of these attachment styles? A crucial determinant lies in the quality of care infants receive. Mothers of securely attached children typically exude warmth, sensitivity to their infants’ signals, and an eagerness to encourage exploration. Conversely, mothers of insecurely attached children tend to provide less sensitive parenting, often delivering inconsistent feedback. Resistant infants may find themselves in a turbulent emotional landscape, as their mothers vacillate between enthusiasm and neglect, leaving them anxious and resentful.

For those with avoidant attachment styles, mothers may overstimulate their children or remain unresponsive to their signals, coupled with negative attitudes. In both cases, infants learn to cope by avoiding their parents, seeking solace in detachment.

While infant characteristics, like prematurity or temperament, can influence attachment styles, caregiver qualities emerge as pivotal determinants. Caregiver warmth, sensitivity, and consistency in responding to an infant’s needs hold the key to forging secure attachments. In the intricate dance of attachment, it is the caregiver’s steps that often set the rhythm, shaping the patterns that will resonate through an infant’s life.

The intricate tapestry of attachment patterns is woven with threads of cross-cultural diversity, reflecting the kaleidoscope of child-rearing practices worldwide. As we traverse different corners of the globe, the percentage of children embracing secure or insecure attachment styles undergoes fascinating transformations, shaped by cultural norms and values.

In the mosaic of human cultures, consider Germany, where independence is nurtured and clingy behavior discouraged in children. Unsurprisingly, German infants often weave a fabric of avoidant attachment, with a tendency to maintain emotional distance more than their counterparts raised in the United States.

Venturing further, we encounter Japan, a culture where parents rarely entrust their infants to the care of strangers. Here, a tapestry of attachment is colored by greater separation anxiety and an inclination toward resistant attachment compared to children raised in the United States.

These cross-cultural variations in attachment patterns underscore the profound influence of cultural contexts on the development of early bonds. Cultures, with their unique child-rearing practices and societal norms, shape the threads that weave the intricate fabric of attachment.

The influence of early attachments extends far beyond infancy. Like threads that carry patterns across a tapestry, the impact of these early bonds ripples through the lifelines of individuals. Bowlby’s assertion that early attachments lay the foundation for future social relationships resonates strongly with empirical evidence.

In the preschool years, children classified as securely attached tend to emerge as more sociable with their peers. They weave a vibrant social fabric, adorned with more friendships and positive interactions than their insecurely attached counterparts.

As childhood unfolds into middle years, the tapestry of attachment continues to define the quality of social bonds. Securely attached children cultivate better relationships with peers, forging closer friendships that endure the test of time.

Remarkably, the threads of attachment stretch across generations. Adults’ attachments to their parents cast a shadow on how their own children form attachments. This intergenerational legacy unfolds because parents’ attachment styles influence their interactions with their children. The tapestry of outcomes is most radiant when children secure attachments with both parents, while the shadows loom darkest when both attachments are insecure.

Yet, to maintain the vibrancy of these attachment threads, the loom of sensitive caregiving must persist throughout childhood. The tapestry of attachment is not static; it evolves, adapts, and carries the echoes of early bonds into the symphony of life’s relationships.

Parenting Styles

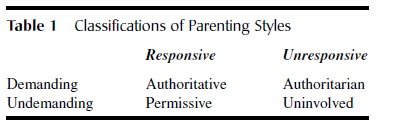

In addition to warm, responsive parenting, Erik Erikson and others have claimed that a second dimension of parenting, the amount of demands and controls the parents place on their children, also plays an integral role in children’s and adolescents’ social development. Parents can be categorized as being either high or low on each of these dimensions (Table 1).

In the grand tapestry of human development, the patterns of parenting are threads that weave the fabric of a child’s social growth. Erik Erikson, in conjunction with other luminaries in the field, posits that the multifaceted tapestry of parenting includes two vital dimensions: warmth and control. Each parent, like a weaver at a loom, combines these dimensions to craft a unique parenting style.

Picture a loom with two levers. On one side, there is warmth and affection, like the sun’s gentle rays embracing a budding flower. On the other side, there is control and demand, akin to a trellis guiding the vine’s growth. These levers can be adjusted to create a symphony of parenting styles, each with its own melody.

In the rich soil of the 1960s and 1970s, Diana Baumrind, like a diligent gardener, sowed the seeds of knowledge through extensive research on the parent-child relationship. Her observations bore fruit in the form of three distinct parenting styles, and later, developmental psychologists Eleanor Maccoby and John Martin contributed a fourth.

Authoritative Parenting: A style that radiates warmth and affection, like a nurturing sunbeam. Authoritative parents embrace their children with love and set expectations for their behavior. They are responsive to their children’s thoughts and feelings, fostering a bond built on trust. These parents encourage their children to grow, allowing them age-appropriate independence while providing guidance through controlled boundaries.

Authoritarian Parenting: In the authoritarian garden, control looms large, but warmth is scarce. Here, rules proliferate like sturdy trellises, and compliance is expected. These parents demand obedience and may employ punitive measures to enforce it. Warmth may be overshadowed by the imposing structure of authority.

Permissive Parenting: This garden, rich in warmth, allows children to bask in the nurturing rays of affection. Permissive parents are caring and lenient, often granting their children significant freedom to make their own choices. They may hesitate to impose controls, believing in their children’s capacity for self-guidance.

Uninvolved Parenting: In the barren soil of uninvolved parenting, both warmth and control are scarce. These parents, like absent gardeners, provide little emotional support and have few expectations. Their children may navigate life’s garden with minimal guidance.

These diverse styles of parenting reflect the intricacies of the parent-child relationship, and like the seasons in a garden, they evolve over time. The loom of parenting, with its levers of warmth and control, shapes the fabric of a child’s social development, each thread contributing to the unique tapestry of their growth.

Table 1 Classifications of Parenting Styles

Table 1 Classifications of Parenting Styles

Children raised by authoritative parents have the best social and academic outcomes. They have high selfesteem, are successful in school, and are well liked by their peers. Children raised in authoritarian households tend to have average social and cognitive competencies and during adolescence tend to be more conforming to their peers. Children raised by permissive parents tend to have low cognitive and social competencies. They often are immature and lack self-control and are more likely to get involved with delinquent behavior than children whose parents set controls for them. The worst outcomes are associated with uninvolved parenting. These children tend to perform poorly in school, display aggressive behavior during childhood, and are at risk for delinquent behavior as adolescents.

Because these findings are correlational, the outcomes are not necessarily due to the parenting style. It is possible that easy-going, intelligent children elicit more authoritative parenting than do difficult children. As stated earlier, whereas parents influence their children, the children also impact the parents.

Working-class parents are more likely to take an authoritarian approach to parenting, and tend to display less warmth than do middle-class parents. In addition, they are less likely to reason with, negotiate with, or foster curiosity and independence in their children. These differences can be explained by the power differences in blue and white-collar occupations. Working-class parents tend to have little power in the outside world and have to defer to their bosses. This leads to a perception of the world as hierarchical. These parents therefore stress obedience to their children, because it is a skill that will help them survive in a bluecollar world. Middle and upper-class parents also attempt to teach their children skills that will help them negotiate their futures. These parents focus on instilling initiative, curiosity, and creativity because these skills are relevant in a white-collar environment.

Siblings

Among the myriad of relationships humans experience, none may be as enduring as that between siblings. This familial bond, often stretching over a lifetime, undergoes fascinating transformations across the stages of development.

Birth Order and Sibling Dynamics: Birth order plays a pivotal role in shaping sibling relationships. Older siblings frequently assume leadership roles, influencing the choice of activities and how they are conducted. They are both the architects of camaraderie and the engineers of sibling rivalry. Younger siblings, in turn, often find inspiration in their elders, mirroring their behavior and choices. However, as siblings age, birth order’s influence tends to wane, and relationships shift toward greater equality by early adolescence.

Factors Shaping Sibling Relationships: The intricate tapestry of sibling relationships is woven with threads of various factors. Gender, for instance, plays a significant role. Same-sex siblings often report closer relationships than those of different genders. Intriguingly, brother-brother relationships often exhibit more conflict. This divergence in sibling dynamics continues into adulthood, with sister relationships often being characterized by profound intimacy.

The age gap between siblings is another factor at play. Close age proximity can breed both warmth and conflict. With minimal separation, siblings engage in frequent comparisons, resulting in more clashes over resources and perceived inequities.

The influence of parents on sibling relationships should not be underestimated. When parents display favoritism toward one child, sibling antagonism tends to escalate. The least-favored child may also grapple with adjustment difficulties. Sibling rivalry often finds its roots with the arrival of a new baby. The older children may witness a decline in positive interactions with their parents and an uptick in restrictive and punitive behaviors. Jealousy can arise as these changes become associated with the new arrival.

Sibling rivalry tends to intensify as the younger child reaches toddlerhood. Armed with newfound abilities, they may assert themselves through physical means or by seeking their parents’ attention. The rivalry’s intensity often peaks during middle childhood, particularly in same-gender or closely aged sibling pairs. However, as adolescents establish their own social worlds and interactions decrease, sibling rivalry generally subsides.

Positive Aspects of Sibling Relationships: Amidst the challenges of sibling dynamics, positive aspects shine brightly. Siblings often serve as pillars of social support, providing emotional sustenance during uncertain times. The intimacy observed in sister relationships can make them particularly effective in this role.

Siblings also double as mentors and role models. Older siblings often guide their juniors through cognitive, physical, and social challenges, either by direct instruction or by modeling behavior. This dynamic benefits both parties, enhancing their academic aptitude and skill acquisition.

Lastly, interactions with siblings contribute significantly to children’s social cognitive development. These exchanges sharpen social skills, enrich emotional understanding, and foster perspective-taking abilities. In this complex web of sibling relationships, a tapestry of experiences unfolds, weaving together a lifelong bond that shapes and enriches the lives of those involved.

Peer Relationships

Parents play a pivotal role in shaping their children’s social experiences, both directly and indirectly. Their choices, such as where they reside, the educational institutions they select, and their participation in extracurricular activities, significantly impact the potential peer groups available to their children. Moreover, parents act as facilitators, arranging playdates and social gatherings for their young ones. These early interactions set the stage for developing essential social skills.

Beyond the logistics of socialization, parents serve as role models, exhibiting behaviors that guide their children’s interactions with peers. They can actively mentor their children on how to navigate the complexities of social relationships, imparting valuable insights and strategies. The parenting style employed by parents also plays a substantial role in their children’s sociability. Authoritative parents, characterized by warmth and reasonable boundaries, tend to raise children with more developed social skills compared to those raised in authoritarian or uninvolved environments.

The significance of these parental influences on peer relationships becomes apparent when considering the profound impact of social skills on a child’s popularity. Popular children often exhibit traits such as composure, extroversion, and friendliness. They engage in prosocial behaviors, rarely causing disruptions or resorting to aggression. Furthermore, they demonstrate advanced perspective-taking abilities, enabling them to understand others’ viewpoints effectively. However, certain patterns of social interaction can hinder popularity and even lead to adverse outcomes.

One such pattern is observed in hostile and impulsive children, who struggle with perspective-taking and frequently misinterpret the intentions of their peers as hostile. This distorted perspective can lead them to react aggressively, making them prone to delinquent behaviors as they progress into adolescence.

Another group at risk comprises withdrawn children, who may display passive and socially awkward tendencies. These children often anticipate negative treatment from their peers and become overly sensitive to criticism, reinforcing their belief that they are disliked. Consequently, they adopt a submissive interaction style, avoiding social engagement. This isolation often results in feelings of loneliness and raises the risk of depression and low self-esteem. However, it’s important to note that not all children who engage less with others are socially inept; some merely prefer more intimate social circles.

Physical appearance also exerts a notable influence on popularity, with attractive children generally enjoying more popularity than their less attractive peers. Additionally, the timing of puberty onset can shape social dynamics. Boys who mature early often excel in sports, bolstering their social status. In contrast, early-maturing girls may face teasing and challenges as they are the first to undergo puberty within their peer group, potentially impacting their popularity in a different way.

In conclusion, parental choices and behaviors play a significant role in shaping children’s peer relationships and social development. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for promoting healthy social interactions and helping children navigate the complexities of peer relationships successfully.

Gender differences in peer relationships manifest early in childhood, well before the onset of puberty. As early as age 2, children begin to exhibit preferences for playing with peers of their own gender. Girls tend to gravitate toward other girls, while boys start preferring same-gender playmates around age 3. This early inclination toward same-sex play is not just a preference; it often involves active avoidance of peers of the opposite gender. Consequently, boys and girls inhabit distinct social realms during their formative years, each marked by unique play styles, toy preferences, activities with friends, and conflict resolution approaches.

Boys typically engage in more active and aggressive play, often participating in rough-and-tumble activities not as common among girls. They tend to form larger playgroups and often involve themselves in competitive games. Within these boy groups, dominance hierarchies often emerge, where power dynamics come into play to establish each child’s standing within the group. As boys are often concerned about their status within these groups, their communication frequently revolves around issues of dominance. In cases of conflict, such as disputes over toys, boys are more likely to employ verbal or physical aggression to resolve these conflicts.

In contrast, girls tend to be more communicative and nurturing in their play. They often form close-knit friendships with one or two best friends, which are characterized by emotional closeness and intimacy. This pattern of forming deep connections continues into middle childhood and beyond. Girls often report having closer friendships compared to boys. When conflicts arise among girls, they are more inclined to seek compromise and attempt to resolve issues amicably. If girls do exhibit aggression, it is often in the context of attempting to harm someone’s social relationships rather than causing physical harm.

Throughout childhood, children’s friendships are typically based on shared activities – they form connections with those they engage in activities with. However, as children transition into adolescence, friendships take on a greater emphasis on trust and intimacy, particularly among girls. Adolescent girls often turn to their friends for emotional support and understanding. While adolescent boys may share more with their friends than they did as children, their friendships continue to be primarily rooted in shared recreational activities.

The transition to adolescence brings several other changes to peer relationships. Peer groups expand in size, and their gender composition shifts from childhood to adolescence. Preadolescence sees the formation of cliques, small groups comprising approximately five or six friends who spend most of their time together. Cliques tend to be homogeneous in terms of gender, age, grade, and ethnic background. As adolescence progresses, larger, reputation-based groups known as “crowds” emerge. These crowds are mixed-gender and can encompass multiple cliques. Members of a crowd often share similar norms, values, and interests, providing both a group identity and a status level within the peer context. Crowds may be associated with labels like “jocks” or “brains,” contributing to adolescents’ sense of belonging and social identity.

Australian ethnographer Dexter Dunphy introduced a comprehensive model that outlines how peer group structures evolve during adolescence, shedding light on the intricate dynamics of dating and romantic relationships during this transformative phase. This model encompasses five distinctive stages that illuminate the changing landscape of adolescent peer interactions.

In the initial stage, adolescents tend to be relatively isolated from the opposite sex, predominantly associating with members of their same-sex cliques. Gender segregation is evident as boys and girls primarily engage with their respective peers. As this phase unfolds, Dunphy’s second stage sees the emergence of crowds as boys’ and girls’ cliques begin to interact at an intergroup level. This interaction sets the stage for the subsequent stages of development.

The third stage sees the advent of dating, particularly among the higher-status individuals within these crowds. These early couples often serve as role models for romantic relationships and mentors for other members of their cliques. Crowds continue to develop in the fourth stage as adolescents begin to interact with members of the opposite sex on an interpersonal level, further blurring the gender lines that were once more distinct. Finally, in the fifth and last stage, the crowds gradually disintegrate, giving way to loosely associated groups of couples as adolescents explore more intimate, one-on-one relationships.

There is substantial evidence supporting the idea that these shifts in peer group structure significantly influence dating and romantic relationships during adolescence. Adolescents who maintain close friendships with peers of the opposite sex during early adolescence are more likely to integrate into mixed-sex social networks in their mid-adolescent years. This integration, in turn, enhances their likelihood of entering romantic relationships. Interactions with peers of the opposite sex also contribute to the development of social and romantic competence.

Early dating experiences in adolescence often involve superficial interactions and frequently occur within group settings. While these relationships offer opportunities for leisure activities and the exploration of emerging sexual feelings, they tend to prioritize attachment and caregiving to a lesser extent. According to B. Bradford Brown, a psychology professor at the University of Wisconsin, adolescents in this phase of dating place greater emphasis on self-discovery and self-perception rather than the qualities of their romantic relationships. This initial exploration of dating helps adolescents build confidence in their ability to relate to the opposite gender and see themselves as capable dating partners.

In the subsequent developmental phase, adolescents increasingly focus on how their romantic relationships are perceived by their peers. For status-related reasons, merely having a romantic partner can become more important than the nature of the relationship itself. Adolescents are mindful of how their romantic choices affect their social standing, as relationships can either enhance or potentially damage their social status within their peer group.

As youth progress, they shift their focus away from external perceptions and concentrate on the quality of the relationship itself. This shift reflects growing confidence in their ability to navigate romantic interactions and a greater acceptance of their reputation and social status among peers. At this juncture, deeper attachments to romantic partners can develop, marked by heightened emotional intensity and intimacy. Consequently, these relationships tend to be more satisfying than those in the earlier phases.

In late adolescence or early adulthood, a further shift is anticipated as youth contemplate whether to commit to a long-term partnership with their romantic counterparts. This phase reflects a maturation of their perspective on romantic relationships, as they weigh the prospect of enduring commitment.

Adolescents who exhibit withdrawn or aggressive interaction styles may encounter challenges when it comes to forming healthy romantic relationships, and these difficulties can have lasting implications for their development.

Withdrawn adolescents often struggle to establish connections within same-sex cliques and, consequently, find it challenging to integrate into mixed-sex peer groups. This limitation can be detrimental because they miss out on the valuable learning experiences that informally dating within their peer group provides. These youths may lack a support network for exploring ideas and concepts related to romantic relationships, which can hinder their ability to develop the appropriate levels of intimacy with their romantic partners when they eventually do begin dating.

On the other hand, aggressive adolescents face a unique set of obstacles. While they may have a peer group, it often consists of delinquent peers who exhibit antisocial behaviors. Consequently, their romantic partners may also display similar antisocial tendencies. Given their aggressive interaction styles, these adolescents are at a heightened risk for experiencing psychological and physical aggression within their romantic relationships. Additionally, they tend to engage in sexual activity at an earlier age than their peers, which can lead to a host of associated challenges and risks.

Early maturation presents yet another set of risks for adolescents. Those who mature early often initiate romantic relationships earlier than their on-time or late-maturing counterparts. Early maturing girls, in particular, may find themselves dating older boys, who may have a delinquent orientation. This circumstance places these girls at an increased risk for engaging in deviant behaviors and early sexual activity. Unfortunately, early-maturing girls not only tend to engage in sexual activity earlier than their peers but also face a higher risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases and experiencing unintended pregnancies.

In summary, adolescents with withdrawn or aggressive interaction styles face distinct challenges when it comes to forming healthy romantic relationships. Withdrawn adolescents may struggle to find the necessary support and learning opportunities within their peer groups, hindering their ability to establish intimacy with romantic partners. Conversely, aggressive adolescents may find themselves in relationships characterized by antisocial behaviors and a higher risk of aggression. Furthermore, early maturation can compound these challenges, placing adolescents at risk for engaging in risky behaviors and experiencing negative consequences in their romantic lives. It is essential for professionals and caregivers to recognize these challenges and provide appropriate guidance and support to help these adolescents navigate the complexities of romantic relationships successfully.

Adult Relationships

Adult relationships, particularly in the context of marriage and family dynamics, undergo significant transformations, bringing about unique challenges and benefits.

In the fourth phase of romantic relationships, individuals actively seek partners with whom they can commit to long-term relationships, often contemplating marriage. Research suggests that marriage is associated with various benefits, including increased happiness, better overall health, and enhanced financial well-being. One explanation for these advantages is that individuals with these positive qualities are more likely to enter into marriages. However, this effect appears to be more than just self-selection, as individuals who have experienced the loss of a marriage through widowhood or divorce tend to fare worse than their single counterparts. This implies that the benefits of marriage extend beyond mere self-selection.

In terms of emotions and psychological well-being, men tend to derive more benefits from marriage than women. More men report being happily married, and marriage is linked to improvements in men’s physical and emotional health. For women, the quality of the relationship is more crucial than marital status itself. Marriage appears to be advantageous for women when the relationship is healthy, but when the relationship is strained or troubled, women often experience more significant negative effects compared to men. One potential explanation for this gender difference is that men are more likely to rely primarily on their spouses for emotional intimacy and social support.

Gender differences are also evident in other family relationships. Women tend to excel in kin-keeping skills, such as maintaining contact through phone calls, sending birthday cards, and making visits, which leads to closer family relationships involving women compared to those involving men. Men, who often have weaker kin-keeping skills, are at a higher risk of experiencing a decline in intimacy with their children following divorce. This gender difference is also observable in adults’ relationships with their parents. Daughters are more likely than sons to directly provide social support and care to elderly parents. When sons take on caregiving roles, they typically assume managerial responsibilities rather than directly providing care.

Among all familial relationships, sibling relationships tend to be the longest-lasting. These relationships carry varying degrees of significance throughout life, with particular importance in early and late adulthood. In early and middle adulthood, individuals often prioritize their families and careers, leading to a somewhat diminished focus on sibling relationships. However, in late adulthood, siblings regain importance as a vital source of support. Strong relationships with sisters in late adulthood appear to protect against depression, while close relationships with brothers do not yield the same effect. This positive impact of relationships with sisters likely arises from the high levels of intimacy characterizing these bonds.

Peer relationships also undergo changes in adulthood. The number of friends typically decreases after young adulthood, as individuals allocate more time and attention to family and career responsibilities. However, the number of close, intimate friendships tends to remain relatively stable throughout adulthood. Similar to earlier life stages, women’s friendships tend to be more intimate than men’s. Women often engage in discussions about personal matters with their friends, while men are more inclined to participate in leisure activities as a form of bonding.

In conclusion, adult relationships are complex and dynamic, influenced by factors such as gender, marital status, and life stage. These relationships can bring both benefits and challenges, underscoring the importance of understanding their unique dynamics for individual well-being and social support throughout adulthood.

Community Effects

Community effects, particularly the impact of living in low socioeconomic status (SES) neighborhoods, can have profound consequences on the development and well-being of children and adolescents. Approximately 20% of U.S. infants and children grow up in families living below the poverty threshold, and their experiences in these neighborhoods can significantly shape their life trajectories.

Children and adolescents residing in impoverished neighborhoods often face a multitude of challenges, including crowded living conditions, subpar educational opportunities, inadequate access to nutrition and healthcare, and exposure to violence and drug-related issues. Consequently, it’s not surprising that living in low-SES neighborhoods is correlated with negative outcomes across various domains. These children are at a higher risk of experiencing poor physical health, lower academic achievement, and suboptimal school performance. Additionally, they are more likely to grapple with social, emotional, and behavioral problems and become involved in criminal activities, delinquency, and high-risk sexual behavior. The most dire outcomes tend to be observed among those living in extreme or persistent poverty.

Three theories have been proposed to elucidate how poverty influences the well-being of children and adolescents:

- Community Resource Model: This model posits that the quality, quantity, and diversity of community resources play a mediating role in determining well-being. Resources such as schools, social services, recreational programs, and employment opportunities are essential for child and adolescent development. In low-SES neighborhoods, the availability and quality of these resources are often compromised, which can contribute to negative outcomes.

- Parental Mediation Model: According to this model, parent attributes and characteristics of the home environment serve as mediators between parents’ economic hardship and their children’s well-being. Economic stress can place a significant burden on parents, affecting their ability to provide quality parenting. Parental stress is often associated with lower levels of warmth and harsh parenting practices. High levels of parental warmth and effective monitoring of children can act as protective factors, mitigating the adverse effects of low-SES environments.

- Community Norms and Social Control Model: This model suggests that formal and informal community institutions help regulate residents’ behavior in accordance with prevailing social norms. However, in impoverished neighborhoods, especially those with high rates of single parenthood, social organization may be lacking, leading to higher rates of crime and vandalism. This lack of social control is exacerbated when there is minimal neighborhood monitoring, allowing peer groups to exert negative influences on adolescent outcomes.

In summary, growing up in a low-SES neighborhood can have far-reaching consequences for the physical, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral development of children and adolescents. Understanding the interplay between community factors, parenting practices, and social norms is crucial for developing effective interventions aimed at improving the well-being of youth in impoverished neighborhoods. It underscores the need for comprehensive strategies that address not only individual and family factors but also the broader community context to support positive development and outcomes for children and adolescents.

References:

- Adams, G. R., & Berzonsky, M. D. (Eds.). (2003). Blackwell handbook of adolescence. Oxford, UK:

- Adolescence Directory On-Line, http://education.indiana.edu/cas/adol/adol.html

- Bornstein, M. , Davidson, L., Keyes, C. L. M., & Moore, K. A. (Eds.). (2003). Well-being: Positive development across the life course. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Brody, H. (1998). Sibling relationship quality: Its causes and consequences. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 1–24.

- Darling, (1999, March). Parenting styles and its correlates. Champaign: ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education, University of Illinois at UrbanaChampaign. Retrieved from http://www.kidneeds.com/diagnostic_categories/articles/parentcorre01.htm

- Durkin, K. (1995). Developmental social psychology: From infancy to old age. Oxford, UK

- Furman, W., Brown, B., & Feiring, C. (1999). The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Gifford-Smith, E., & Brownell, C. A. (2003). Childhood peer relationships: Social acceptance, friendships, and peer networks. Journal of School Psychology, 41, 235–284.

- Lerner, R. M., & Steinberg, L. (Eds.). (2004). Handbook of adolescent psychology (2nd ). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Luthar, S. S. (Ed.). (2003). Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adver Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, P. , & Hart, C. H. (Eds.). (2002). Blackwell handbook of childhood social development. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- University of Minnesota, Center for Early Education and Dev (n.d.). Attachment and bonding. Retrieved from http://education.umn.edu/ceed/publications/early report/winter91.htm

- Walsh, F. (Ed.). (2003). Normal family processes: Growing diversity and complexity (3rd ). New York: Guilford.

- Zimmer-Gembeck, J. (2002). The development of romantic relationships and adaptations in the system of peer relationships. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31(Suppl. 6),216–225.