Sport and recreational-related injuries have become a significant public health concern for physically active persons. For example, in 2006 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that participation in high school sports will result in approximately 1.4 million injuries reported to medical staff at a rate of 2.4 injuries per 1,000 athlete exposures (i.e., practices or competitions). As sport and other physical activities continue to be promoted as part of maintaining and restoring health, there will continue to be an increase in sport-related injuries. These trends have resulted in multifactorial perspectives of injury prediction and prevention. Advances in safety of equipment, improvement to the physical environment, and new policies to protect sport participants have been implemented. Of relevance to this resource, but not likely as well known, are those approaches that involve the monitoring and modifying of psychological factors associated with sport injury.

Psychological Stress and Sports-Related Injury

In the 1960s, Thomas Holmes and colleagues suggested that changes in social stress, as measured by assessing accumulated stressful life events, were a precursor to changes in overall health. Essentially, life events often evoked changes in psychological status that required increased efforts to cope. This response to stress, or stress reactivity, was the mechanism underpinning the relationship between stress and health, whereby as stress demands and coping efforts increased, health would be compromised (e.g., onset of illness, progression of disease). In the1970s, Holmes and later S. T. Bramwell and colleagues were the first to explore this notion in sport. They surveyed American football players and found greater levels of stress were associated with increased likelihood of athletic injury. This prompted further exploration of the relationship between stress and sport injury, yet much of what followed failed to replicate Holmes and Bramwell’s findings. The literature lacked a unifying framework until 1988, when Mark B. Andersen and Jean M. Williams’s model of stress and athletic injury filled an important gap and provided direction for future efforts.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Model of Stress and Injury

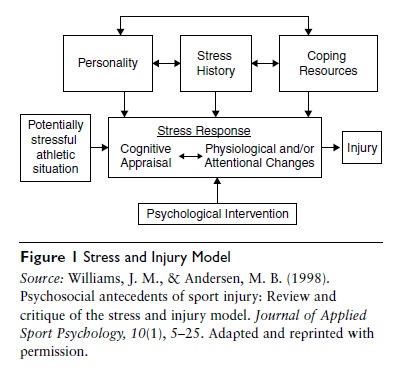

The stress-injury model posits that three categories of psychological risk factors (i.e., personality, history of stress, and coping resources) influence athletes’ response to stressful athletic situations that, in turn, influences the likelihood of athletic injury through various stress-response mechanisms (see Figure 1). In addition to proposing psychological risk factors, their model offered specific avenues for psychological interventions and skills training to buffer adverse stress-related consequences for athletes’ health and to minimize, or ideally prevent, athletic injury.

Stress Response Mechanisms

Cognitive Appraisal

Central to the stress and injury model is one’s cognitive appraisal. Based upon the pioneering work of Richard Lazarus and Susan Folkman, the cognitive appraisal involves a balance (or imbalance) between two perceptions. The primary appraisal reflects perceived demands or threat of the stressor whereas the secondary appraisal reflects perceived personal and situational resources to cope with those demands and/ or threat. When coping resources are perceived to be adequate to manage threat or demands, stress reactivity is minimal. In contrast, an imbalance occurs where one’s perception of stress demands exceeds available coping resources, at which point stress reactivity is heightened.

Figure 1 Stress and Injury Model

Figure 1 Stress and Injury Model

Physiological Considerations

Very little attention has been given to physiological considerations. Within the model, stress responses that were initially described involved increase in muscle tension, which was thought to potentially impair motor control and slow reaction time (RT) that, in turn, may heighten injury vulnerability when engaged in sport competition and/or training. Over time, three additional pathways emerged associating psychological stress to physiological response. Perturbations in visual attention involving peripheral narrowing of visual field were described among highly stressed athletes and were hypothesized to heighten risk for injury (i.e., being blindsided). The other pathways linking stress to injury involved excess autonomic activity (e.g., increases in stress hormones) that were posited to increase injury risk by impairing immune function and other cellular processes necessary for muscle repair following strenuous exercise training, or by altering sleep and associated secretion of growth factors also required for muscle anabolism. To date, excess elevation in psychological stress-related autonomic activity remains as the leading mechanism associated with athletic injury, but the specific causal pathway(s) remains unknown.

Attentional Considerations

In contrast to physiological factors, research studies have explored stress-related implications on attentional performance. Measures of visual and attentional indices have included peripheral narrowing and increased distractibility. In 1999, Mark Andersen and Jean Williams first demonstrated that peripheral narrowing mediated the relationship between injury outcomes and high stress in college athletes, and this was later replicated among high school athletes in 2005 by Traci Rogers and Dan Landers. While stress-related effects upon attentional and visual performance have been examined, there are other avenues (e.g., working memory capacity) that may be very relevant yet remain unexplored in the psychological injury vulnerability literature.

Psychological Factors That Influence Stress Response

Athletes who have a history of stress, a personality that amplifies perceptions of stress demands and/ or reactivity to stress, and few available or effective coping resources are more likely to have cognitive appraisals of athletic situations that heighten their stress-reactivity. For those athletes, the consequences of heightened stress reactivity experienced within a sporting environment increase their risk of injury.

Personality

Research examining personality has measured patterns of behavior likely to exaggerate perceptions of stress demands and/or responses. In the original 1988 model, six likely personality variables were proposed and those included hardiness, locus of control, sense of coherence, competitive trait anxiety (TA), and achievement motivation. After nearly a decade of research, only four of those had received any attention and other characteristics had emerged that seemed appropriate that were not originally included (e.g., dispositional optimism). Today, well over 20 different personality factors have been explored as potentially associated with injury vulnerability. While evidence for an injury-prone athlete personality type has not emerged from any of this literature, very few personality variables have been examined in more than one study. Those exceptions that have been explored across multiple studies are anxiety, locus of control, mood states, and anger. Anxiety is the most frequently measured, and while operational definitions vary considerably across studies, those studies examining competitive TA have consistently demonstrated significant associations with injury. In contrast, the research on locus of control, mood states, and anger remains inconclusive.

Associated with personality, other characteristics and sport-related patterns of behavior involving behavioral genetics may also influence the athletes’ psychological stress and injury vulnerability. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have found particular single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with sport-related ligament injuries. GWAS has not been applied to the study of possible mechanisms linking personality or psychological stress factors to athletic injury. However, behavioral genetic findings associated with mood regulation and conscientiousness identified in the general population may have relevance to athletes’ emotional response to injury and behavioral adherence to recovery protocols. As an emerging area of inquiry, further research is necessary.

History of Stress

Stress history was the initial and continues to be the most commonly examined psychological risk factor associated with injury. Athletes’ history of stress has been examined through measuring three different variables: major life events, daily hassles or minor life events, and prior injury history. Early studies by Holmes and Richard S. Rahe and colleagues measured accumulated life events (or total life stress) irrespective of the specific nature or impact of those events. Over the years, a focus has shifted away from measuring only accumulative life events and toward measures that examine the impact and valence of stressful events, as well as both life and sport-related stressful events typical of athletic populations. The evidence supporting a relationship between life events’ stress and athletic injury is by far the clearest and most consistent.

In contrast to these findings, research examining minor life events or daily hassles has been less clear. By definition, daily hassles occur frequently and therefore contribute to sustained stress activation. Unfortunately, daily hassles have not always been measured in a manner that captures its reoccurring nature; when it has, it has been significantly associated with injury. The third variable, prior injury history, influences athletes’ stress reactivity in a few important ways. Athletes who have been injured previously may be physically and/or psychologically vulnerable to re-injury due to returning to sport prematurely either because physical and/or psychological recovery was not yet complete. For example, athletes may be physically recovered but may still have considerable self-doubt and anxiety. Either independently or conjointly, cognitive and physiological symptoms of anxiety further heighten stress reactivity and may have a more pronounced impact upon cognitive, attentional, and/or physiological functioning. In recent reviews of the literature done by Jean Williams as well as our own recent work, approximately 80% to90% of studies have documented significant relationships between stress history and sport injury. Collectively, the evidence supports the centrality of athletes’ stress reactivity in determining stress-related vulnerability to sport injury.

Coping Resources

Compared to stress history and personality, less attention has been given to coping resources in the injury vulnerability literature. Coping resources involve both internal or personal factors as well as external or environmental factors, which collectively reflect the strengths and vulnerabilities in managing demands of stress. Internal coping resources examined have involved measuring athletes’ general coping behaviors or self-care (quality of nutritional intake, sleep, etc.) and psychological or sport coping skills (regulation of one’s thoughts, energy, attention, emotion, etc.). Researchers have not always been able to demonstrate a significant relationship between internal or personal coping resources and sport injury. When significant links have been reported, they have almost always reflected a protective effect—greater coping was directly or indirectly associated with lower injury risk.

External coping resources have primarily been evaluating the quality, quantity, and/or effectiveness of athletes’ social support networks. In contrast to personal coping resources, results from studies examining social support are quite contradictory. Some studies have reported stress-buffering effects of social support while others have demonstrated increased stress-reactivity and injury risk with greater social support. These contradictory findings are perhaps suggestive of different stress injury mechanisms across different sports.

Psychological Interventions for Health Promotion in Sport

The most exciting avenue of research is the efficacy of psychological interventions to prevent athletic injury. Intervention studies, based on Donald Meichenbaum’s cognitive behavioral stress management (CBSM), involve the provision of education and skills training to athletes aimed to foster adaptive cognitions (e.g., thought stopping, restructuring) and/or manage physiological and attentional functioning (e.g., relaxation, mental rehearsal). To date, intervention studies have yielded medium to very large effects (e.g., 0.67–0.99), and the quality of this research has occurred at the highest level for therapeutic interventions (i.e., a randomized clinical trial). Findings provide strong support for psychological services for athletes to mitigate negative health-related consequences of sport participation (e.g., reduced injury or illness, time loss due to injury).

References:

- Appaneal, R. N., & Habif, S. (in press). Psychological antecedents to sport injury. In J. Waumsely, N. Walker, & M. Arvinen-Barrow (Eds.), The psychology of sport injury rehabilitation (pp. 6–22). Oxford, UK: Routledge.

- Johnson, U. (2007). Psychosocial antecedents of sport injury, prevention and intervention: An overview of theoretical approaches and empirical findings. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 5, 352–369.

- Perna, F. M., & McDowell, S. L. (1995). Role of psychological stress in cortisol recovery from exhaustive exercise among elite athletes. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 2, 13–26.

- Petrie, T. A., & Perna, F. M. (2004). Psychology of injury: Theory, research, and practice. In T. Morris & J. J. Summers (Eds.), Sport psychology: Theory,application, and issues (2nd ed., pp. 547–551). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Wade, C. H., Wilfond, B. S., & McBride, C. M. (2010). Effects of genetic risk information on children’s psychosocial wellbeing: A systematic review of the literature. Genetic Medicine, 12, 317–326.

- Wiese-Bjornstal, D. M. (2010). Psychology and socioculture affect injury risk, response, and recovery in high-intensity athletes: A consensus statement. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports,20, 103–111.

- Williams, J. M., & Andersen, M. B. (2007). Psychosocial antecedents of sport injury and interventions for risk reduction. In G. Tenenbaum & R. C. Eklund (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (3rd ed., pp. 379–403). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

See also: