Self-handicapping is a future-oriented, self-protection strategy used to (a) maintain personal perceptions of competence, control, self-worth, and self-esteem and/or (b) protect or enhance one’s public image in the eyes of coactors or observers. It consists of thoughts, statements, and behaviors that take place in advance of performance, and that increase the likelihood of situational factors being blamed for poor performance but personal factors being credited for good performance.

Variations and Principles

Two forms of self-handicapping have been identified based on the way in which the process unfolds. When cognitions or verbalizations are used to proactively defend or enhance self-worth and self-esteem, they are considered to be self-reported, or claimed, handicaps. Examples of this form of self-handicapping include a focus on (or claims of) temporary illness or injury, situation-specific anxiety, mood fluctuations, or recent exposure to uncontrollable negative events. When proactive defense or enhancement of self-worth and self-esteem involves deliberate, observable acts that could conceivably interfere with performance, they are regarded as behavioral handicaps. Examples of this form of self-handicapping include ingestion of drugs or alcohol, withholding of effort, choosing to perform under less-than-optimal conditions, or providing assistance to competitors.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

From a theoretical perspective, the use of self-handicapping strategies invokes the attributional principles of augmentation and discounting. More specifically, proactively established handicaps permit the individual to augment the role of personal attributes such as ability if performance is good or, alternatively, to discount the importance of personal attributes such as ability if performance is bad. From an empirical standpoint, studies of attributions made for one’s own performance in the presence of potential handicaps provide consistent support for discounting (i.e., self-protection) following failure and occasional support for augmentation (i.e., self-enhancement) following success. Some researchers have suggested that self-enhancement effects might be most evident among individuals with high self-esteem.

Measures of the Construct

Individual differences in self-handicapping tendencies have been assessed in several ways within the sport and exercise domains. The most widely used measure of the construct in these settings is a 14-item version of the Self-Handicapping Scale (SHS) that assesses propensities for excuse making and withholding of effort. Despite its widespread use, this measure has been criticized by some sport researchers on psychometric grounds and because of its generic frame-of-reference, which undermines domain-specific relevance. As an alternative approach, other investigators have utilized an open-ended, listing-of-impediments procedure to examine self-handicapping tendencies among athletes. Overall, the findings from these studies reveal that commitments outside of sport, injury or illness, and training disruptions are the most frequently cited potential handicaps prior to performance and that some athletes do indeed have a greater propensity than others to cite such impediments. What cannot be determined, of course, is the extent to which these obstacles are actual or perceived for any given individual. As such, there is likely to be some measurement error inherent to the listing-of-impediments approach.

A less-frequently used but potentially informative approach to assessing self-handicapping tendencies involves the construction of study-specific inventories containing contextually relevant descriptions of proactive impression-management strategies that are then rated on a “like me” or “not like me” basis. In the youth sport context, these items might include statements such as the following: “Some players fool around at practice and before games.” Then, if they don’t play well, they say that was the reason. or “Some players get involved in a lot of activities outside of sport.” Then, if they don’t play well, they say it was because they were involved in other things. Such statements are clearly anticipatory, reflective of self-handicapping tactics, and explicitly self-presentational in the orientation. Research in physical education (PE) classes has demonstrated that this approach can be informative, and it deserves broader consideration within competitive sport. It could also prove useful for advancing knowledge about context-specific self-handicapping in relation to exercise behavior. At present, the only measure of the construct specific to the exercise domain is the Self-Handicapping Exercise Questionnaire, which assesses exercise impediments related to incorporating exercise into one’s routine, training in an exercise facility, and physical health.

Research in Sport and Exercise

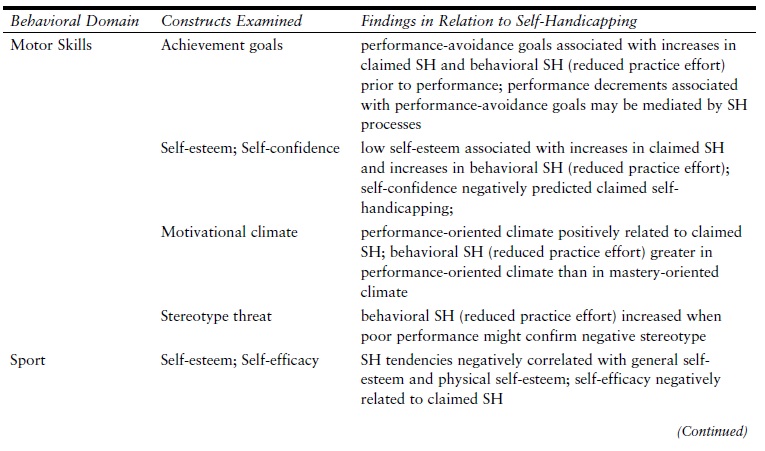

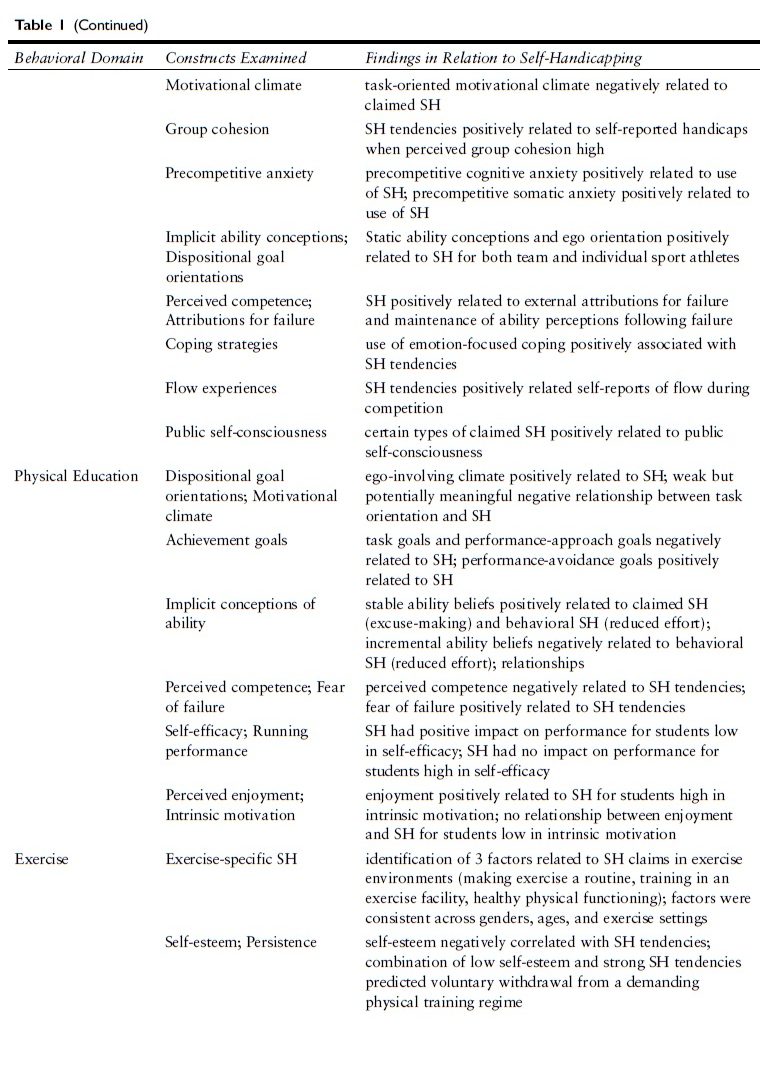

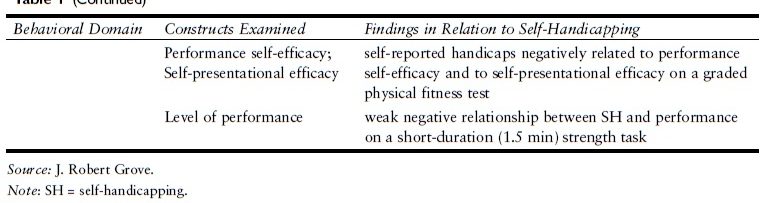

Self-handicapping occurs most often in situations that involve public behaviors that are considered important to the individual and, at the same time, are characterized by uncertainty about the likelihood of a good performance. In such circumstances, poor performance is potentially threatening to private or public self-worth and self-esteem. Because sport and exercise environments often contain most of these elements, it is not surprising that psychologists have taken a keen interest in the correlates and consequences of self-handicapping processes within sport and exercise settings. Table 1 summarizes research findings related to self-handicapping in the areas of motor skills, sport, PE, and exercise. The information is necessarily selective, but it provides an overview of how self-handicapping has been examined in these domains and outlines relationships that have been observed with other psychological constructs.

Table 1 Summary of Findings for Studies of Self-Handicapping (SH) in the Motor Skills, Sport, Physical Education, and Exercise Domains

Table 1 Summary of Findings for Studies of Self-Handicapping (SH) in the Motor Skills, Sport, Physical Education, and Exercise Domains

Several noteworthy observations arise from an inspection of Table 1. First, self-efficacy, self-confidence, and self-esteem have been studied extensively in connection with self-handicapping, and the findings have been consistent across behavioral domains. In general, lower levels of self-efficacy, self-confidence, and self-esteem are associated with higher levels of self-handicapping. The interrelated constructs of achievement goals, dispositional goal orientations, implicit ability conceptions, and motivational climate have also been widely studied in relation to self-handicapping. Regardless of behavioral domain, it appears that a mastery (learning) orientation, which is associated with incremental ability conceptions, results in higher levels of self-handicapping than a performance (outcome) orientation, which is associated with fixed ability conceptions.

Most of the studies within these domains have operationalized behavioral self-handicapping in terms of reduced practice effort. While expected relationships have been observed between various psychological constructs and this index of behavioral self-handicapping, some researchers have expressed concern about heavy reliance on this measure. More specifically, it has proven difficult to assess reliably via questionnaire in sport and exercise settings, and direct, observational data related to practice effort (e.g., number of practice attempts) can be influenced by numerous factors other than self-handicapping. Some consideration may therefore need to be given to other indices of behavioral self-handicapping. Additional consideration should also be given to the correlates and consequences of self-handicapping in relation to real-world exercise behaviors outside of sport and PE settings. Despite some interesting preliminary findings (e.g., an association between self-handicapping tendencies and voluntary withdrawal from demanding physical training programs), it is clear from the summary in Table 1 that relatively little self-handicapping research has been conducted in this domain. Given the importance of real-world exercise behavior to personal health, its social desirability, and the self-presentational issues that surround it, there would seem to be abundant opportunity for more detailed examination of the associated self-handicapping processes.

Conclusion

Self-handicapping is a proactive self-protection and self-enhancement strategy. Classic forms of self-handicapping involve self-protective thought processes or statements that occur in advance of performance (self-reported or claimed handicaps) and pre-event behaviors that might interfere with performance (behavioral handicaps). Numerous psychological constructs have been examined in connection with these forms of self-handicapping in the motor skill, sport, PE, and exercise domains. These constructs have included personal (e.g., anxiety), group (e.g., cohesion), and environmental (e.g., climate) variables. In general, positive self-perceptions, incremental ability beliefs, and mastery-oriented environments are associated with low levels of self-handicapping, while negative self-perceptions, fixed ability beliefs, and performance-oriented environments are associated with higher levels of self-handicapping. Self-handicapping processes within real-world exercise settings deserve closer scrutiny in future research.

References:

- Martin, A. J. (2008). Motivation and engagement in music and sport: Testing a multidimensional framework in diverse performance settings. Journal of Personality, 76, 135–170.

- Ntoumanis, N., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., & Smith, A. L. (2009). Achievement goals, self-handicapping, and performance: A 2 x 2 achievement goal perspective. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27, 1471–1482.

- Prapavessis, H., Grove, J. R., & Eklund, R. C. (2004). Self-presentational issues in competition and sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 16, 19–40.

- Shields, C. A., Paskevich, D. M., & Brawley, L. R. (2003). Self-handicapping in structured and unstructured exercise: Toward a measurable construct. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 25, 267–283.

- Smith, J. L., Hardy, T., & Arkin, R. (2009). When practice doesn’t make perfect: Effort expenditure as an active behavioral self-handicapping strategy. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 95–98.

See also: