The effects of music in sport and exercise contexts have been of interest to researchers for over 100 years. Recent advances in digital music technology and the facility for users to formulate their own playlists have dramatically increased the prevalence of music in both the sports training and health club environments. Even at the high altar of international competition, the use of music has become commonplace as athletes seek ever-more effective means of optimizing their mental and physical states. Interventions assume one of three types depending on when the music is delivered in relation to the task: pre-task, in-task, or post-task. Very little research attention has been given to the post-task application of music as a recuperative tool; therefore, this entry will focus on pre-task and in-task music, which represent the mainstay of its use in the sport and exercise domain. The personal and situational factors that influence music selection will also be introduced.

Pre-Task Music

Research findings indicate that music used before a physical task can serve as a potent stimulant. This is especially so when the task itself requires a high degree of psychological and physical arousal; activities such as weight lifting or sprinting that depend on the use of every major muscle group and a short, intense effort are particularly good examples. In concert with the available research evidence, many athletes have used music as a pretask intervention prior to winning Olympic medals, an example being the swimmer Michael Phelps. Pre-task music may also serve to relax a performer prior to competition as was demonstrated by Olympic gold medalist runner Kelly Holmes at the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens. Further functions include the use of music as a trigger to invoke mental images that are relevant to the task or to emphasize a particular aspect of technique. The suggestions borne by the lyrical content of music can be especially potent in this regard.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

In-Task Music

There is now a wealth of research evidence documenting the effects of music used in accompaniment of various physical tasks. Its principal psychological effects are the enhancement of positive feeling states and arousal and distraction from the unpleasant sensations associated with physical effort and fatigue. It is thought that this distraction effect takes place at a neural level: the nerve signals bearing auditory information (music) taking precedence over those relating to exertion. However, as the lactate threshold is approached, which is, broadly speaking, the intensity at which one can no longer continue to exercise and keep one’s breath, the signals relating to effort become stronger than those pertaining to the music and the distraction effect is reduced.

While music may not divert attention at high exercise intensities, it retains the capacity to elevate feeling states, which may in turn alter our interpretation of effort and fatigue. Music also exerts behavioral consequences on exercisers— namely, an increase in self-selected exercise intensity or an extension of voluntary endurance. Research has shown that music is particularly effective as a work enhancer when movement is synchronized to its rhythmic qualities. This may enhance movement efficiency by establishing a more regular or metronomic work rate. This synchronous use of music is especially applicable to repetitive endurance activities such as running or swimming.

Music Selection

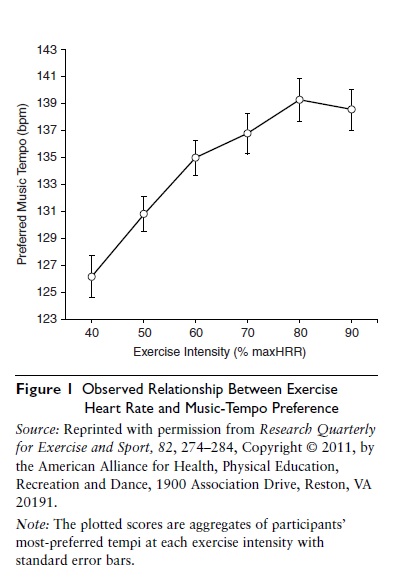

The benefits of music depend on its appropriateness for both the task at hand and the listener in question. In both sport and exercise, the goal generally is to enhance feelings of pleasure and arousal. However, in target sports such as shooting, golf, or archery the aim is typically to sedate rather than to stimulate; therefore, soft or slow music (less than 80 beats per minute [bpm]) is recommended. In terms of heightening arousal, studies have shown that loud music with a fast tempo (over 120 bpm) and pronounced rhythmical features is particularly effective. Indeed, music is most preferred when its tempo is selected with the intensity of the exercise in mind. A range of 125 to 140 bpm would appear to describe the preference for music tempi across the entire range of exercise intensities (e.g., from walking to fast running). In simple terms, as one works harder, one prefers faster music until the preference ceiling of ~140 bpm is reached. The relationship between preferred tempo and heart rate (HR) as plotted on a graph is not linear but curvilinear in nature (see Figure 1).

Music qualities thought to promote pleasure include the melody (tune) and the series of harmonies used. Harmony refers to the simultaneous sounding of notes, which lends music its emotional “color.” Music may prove particularly effective if it bears associations that the listener finds personally motivating. Such associations may be transferred through popular culture, examples being found in the theme music linked with sporting films or events. To be maximally effective, music should be selected with the age, gender, personality (e.g., introversion vs. extraversion), and sociocultural background of the listener in mind.

Figure 1 Observed Relationship Between Exercise Heart Rate and Music-Tempo Preference

Figure 1 Observed Relationship Between Exercise Heart Rate and Music-Tempo Preference

There are now in advance of 100 published studies demonstrating the psychological and work-enhancing effects of music in various sport and exercise contexts. It is entirely possible that carefully selected music may exert longer-term effects such as increased adherence to exercise. Music may exert a compound effect when used in a social environment because it can influence esprit de corps in addition to altering the behavior of supporting crowds or group leaders. In the sporting sphere, music has become part and parcel of many athletes’ pre-event routines and is a potentially powerful tool for the forward-thinking sport psychologist.

References:

- Karageorghis, C. I., Jones, L., Priest, D. L., Akers, R. I., Clarke, A., Perry, J. M., et al. (2011). Revisiting the exercise heart rate-music tempo preference relationship. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 82, 274–284.

- Karageorghis, C. I., Mouzourides, D. A., Priest, D. L., Sasso, T., Morrish, D., & Whalley, C. (2009). Psychophysical and ergogenic effects of synchronous music during treadmill walking. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 31, 18–36.

- Karageorghis, C. I., Priest, D. L., Terry, P. C., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., & Lane, A. M. (2006). Development and validation of an instrument to assess the motivational qualities of music in exercise: The Brunel Music Rating Inventory-2. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24, 899–909.

- Karageorghis, C. I., & Terry, P. C. (2011). Inside sport psychology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

See also: