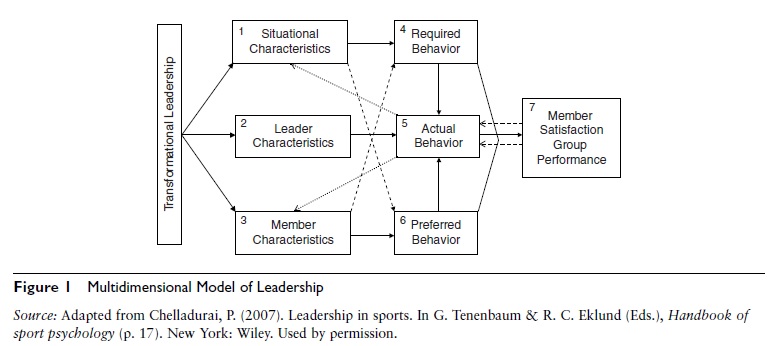

An established model of leadership in sports is Packianathan Chelladurai’s multidimensional model of leadership (MML). This model was the substance of a doctoral dissertation in management science. It represented a synthesis and reconciliation of the models of leadership found in the mainstream management literature. These preexisting models tended to focus more on either the leader, or the member, or the situation. However, as leadership is a concept that encompasses all three factors—the leader; the members; and the organizational context including goals, structures, and processes—it was reasonable to propose the model illustrated in Figure 1.

A unique feature of the model is that it includes three states of leader behaviors. Required behavior (Box 4) is the set of prescriptions and proscriptions of the situation in which leadership occurs. Required behavior is mostly defined by the situational characteristics (Box 1) that include the goals of the group, the type of task (e.g., individual vs. team, closed vs. open tasks), and the social and cultural context of the group. The nature of the group defined by gender, age, skill level, and such other factors would also partly define required behavior. Preferred behavior (Box 6) refers to the preferences of the followers for specific forms of behavior (such as training, social support, and feedback) from the leader. Members’ preferences are a function of their individual difference characteristics (Box 3) such as personality (e.g., need for affiliation, tolerance for ambiguity, attitude toward authority) and their ability relative to the task at hand. Members are also aware of the situational requirements; thus, their preferences are influenced by those requirements. The actual behavior (Box 5, i.e., how the leader actually behaves) is largely based on leader characteristics (Box 2) in terms of personality, expertise, and experience. However, the leader would also be constrained to abide by the requirements of the situation (Box 4) and to accommodate member preferences (Box 6) as well.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Another significant feature of the MML is its congruence hypothesis. That is, the model specifies that the desired outcomes of individual and team performance, and member satisfaction will be realized if the three states of leader behaviorare congruent with each other. Any misalignmentamong the three states of leader behavior would diminish performance and/or satisfaction. Further, if there is continued discrepancy between actual leader behavior and the other two states of leader behavior, the leader’s position within the group would become untenable. The dynamic nature of leadership is highlighted in the model with backward arrows indicating feedback from attained performance and/or member satisfaction. That is, the leader may begin to exhibit more of task-oriented behaviors if she or he feels that the performance was below expectations. On the other hand, leader behaviors may begin to be more interpersonally oriented if it is felt that members were low on morale and/or satisfaction.

Figure 1 Multidimensional Model of Leadership

Figure 1 Multidimensional Model of Leadership

In 2007, Chelladurai made one significant modification to the model. It was the incorporation of the concept of transformational leadership into the multidimensional model. In his view, leadership exhibited by coaches is largely concerned with pursuit of excellence. In the process of pursuing excellence, the person is transformed from a relatively unaccomplished novice into an expert performer. Thus successful coaches do exhibit transformational leadership and, as such, incorporating the concept into the model was necessary as well as easy. In essence, the coach as the leader transforms member characteristics in terms of aspirations and attitudes and changes the situational requirements by articulating a new mission and convincing the members of the viability of the mission and their capacity to achieve that mission.

The idea (as shown in Figure 1) that transformational leadership influences leader characteristics (Box 2) would be most relevant where a coach has one or more assistant coaches. That is, the chief coach would attempt to transform the assistant coaches in the same way he or she would transform player characteristics. If there is only one coach, it would mean that the coach would change his or her own characteristics to fit the transformational mold and attempt to change the situational characteristics as well as the characteristics of the members as indicated by the dotted arrows flowing from actual behavior (Box 5) to situational characteristics (Box 1) and to member characteristics (Box 3).

A theory is useful only to the extent that the variables of the study can be measured and the relationships among the variables can be verified. With this in mind, Chelladurai developed the Leadership Scale for Sports (LSS) to measure the three forms of leader behavior contained in the model. It is composed of 40 items to measure these five dimensions of leader behavior: training and instruction (13 items), democratic behavior (9 items), autocratic behavior (5 items), social support (8 items), and positive feedback and rewarding behavior (5 items). The response format is a 5-point scale ranging from (1) always; (2) often, about 75% of the time; (3) occasionally, about 50% of the time; (4) seldom, about 25% of the time; to (5) never. The scale has been used to measure athletes’ preferences, their perceptions of their coaches’ behavior, and coaches’ perceptions of their own behavior pertaining to those five dimensions of behavior.

The psychometric properties of the LSS have been verified and supported in several studies. However, the subscale of autocratic behavior has been shown to be weak in almost all studies. One reason for such low internal consistency estimates is that the items in the subscale relate to three different forms of behavior—being aloof, being authoritative, and making autocratic decisions. Another conceptual issue that plagues the dimension of autocratic behavior is that whether a coach should be autocratic or democratic is dependent on the attributes of the problem in question. The items in this subscale do not capture the situational contingencies. The entry on “Decision-Making Styles in Coaching” (this volume) deals with contextual differences that indicate the degree of participation by team members in decision making.

There has been an attempt to improve the LSS by James J. Zhang and his colleagues. Their Revised LSS includes the five dimensions, the instructions, and the response format of the original LSS. It also includes a new dimension titled situational consideration behaviors. However, the Revised LSS has not been subjected to confirmatory analyses and the new dimension is subsumed by the original five dimensions. Therefore, parsimony would dictate the use of the original LSS.

Commentary

Both the MML and the LSS have been used and tested in several studies. Much of the research on the notion of congruence suggested in the model has been restricted to only two states of leader behavior—preferred behavior and perceived behavior used as a proxy for actual behavior. While the notion of congruence between these two states of leader behavior has been largely supported, it is disappointing that the congruence among all three states of leader behavior has not been tested adequately. Researchers could have omitted required behavior from consideration because of the difficulty of measuring required behavior. In his original research, Chelladurai employed the average of coaches’ reporting of their own behavior as a surrogate of required behavior. Future research may consider asking expert coaches specifically about what should be the required behavior in a given situation defined by age, gender, ability level, goals of the program, and so on. The average of these responses may be used as required behavior in the relevant situation.

In developing the LSS, Chelladurai resorted to the leadership scales then popular in the mainstream management literature such as the Leadership Behavior Description Questionnaire (LBDQ). He collated more than 100 items from these scales and reworded them to suite the coaching context. However, he was forced to reduce the scale to 99 items because the computers available at his university at that time could not handle more than that number of items. He administered the initial questionnaire to members of the university basketball teams in Canada and derived five dimensions of leader behavior through exploratory factor analysis. Subsequent research studies employing the more sophisticated confirmatory factor analysis has supported the robustness of the LSS. While these steps are acceptable, it is necessary to generate sport specific items, group them into meaningful categories, administer the questionnaire to different teams in different sports, and subject the data to confirmatory factor analyses. Furthermore, the LSS does not tap into the dimensions of transformational leadership, which has been recently incorporated into the MML. It is expected that future research will focus on refining the existing subscales and developing new subscales for transformational leadership.

Finally, it must be noted that although the MML was advanced in research related to leadership in athletics, the model itself is applicable to any context (e.g., business, industry, military) where leadership is a critical process. The model, after all, is a synthesis of other models from business and industry. Thus, reversing the process and applying the model to other contexts including business and industry is feasible. While the situational and member characteristics may vary from context to context, the concepts of required, preferred, and actual behavior are meaningful in any context. On a different note, Chelladurai included group performance and member satisfaction as the outcome variables. But other outcomes such as individual performance, individual growth, group cohesion, group solidarity, commitment, identification, and organizational citizenship can easily be accommodated in the model. Further, business outcomes such as profitability, market share, and return on investments can be used as outcome variables.

References:

- Chelladurai, P. (1978). A contingency model of leadership in athletics. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Department of Management Sciences, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada.

- Chelladurai, P. (1993). Leadership. In R. N. Singer,M. Murphy, & K. Tennant (Eds.), The handbook on research in sport psychology (pp. 647–671).New York: Macmillan.

- Chelladurai, P. (2007). Leadership in sports. In G.Tenenbaum & R. C. Eklund (Eds.). Handbook of sport psychology (3rd ed., pp. 113–135). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Chelladurai, P., & Carron, A. V. (1978). Ottawa: CAHPER, Sociology of Sport MonographSeries.

- Chelladurai, P., & Riemer, H. (1998). Measurement of leadership in sports. In J. L. Duda (Ed.), Advancements in sport and exercise psychology measurement(pp. 227–253). Morgantown, WV: Fitness InformationTechnology.

- Chelladurai, P., & Saleh, S. D. (1980). Dimensions of leader behavior in sports: Development of a leadership scale. Journal of Sport Psychology, 2(1), 34–45.

- Zhang, J., Jensen, B. E., & Mann, B. L. (1997).Modification and revision of the Leadership Scale forSport. Journal of Sport Behavior, 20(1), 105–121.

See also: