Reinforcement and punishment are common verbal and nonverbal responses to successes and failures in sport, exercise, and rehabilitation contexts. These practices may be best understood in the context of operant conditioning. This entry defines reinforcement and punishment, reviews evidence of their frequency in sport, identifies their motivational implications, and reviews mechanisms for those effects.

Response Consequences in Operant Conditioning

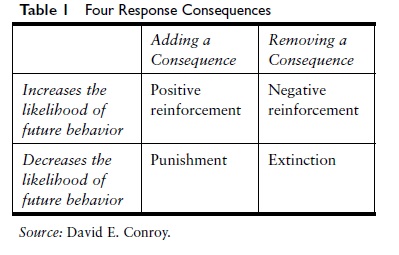

Operant conditioning is a process in behaviorist theory by which behaviors are influenced by their consequences. Over time, people learn to associate certain behaviors with specific consequences and, to the extent that the consequences of certain behaviors are satisfying, those behaviors are more likely to be repeated. Correspondingly, to the extent that the consequences of certain behaviors are unsatisfying, those behaviors become less likely to be repeated. Table 1 illustrates four general response consequences in operant conditioning as a function of (a) whether the consequence involves adding or removing a response and (b) whether the response is intended to increase or decrease the future likelihood of a particular behavior.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The two response consequences that aim to increase the likelihood that a desired behavior will be repeated are positive and negative reinforcement. Positive reinforcement refers to the process of introducing a satisfying consequence following a desirable behavior that will increase the likelihood of that behavior being repeated. For example, in sport, coaches often use verbal praise as a reinforcement following a desirable play by an athlete. Negative reinforcement refers to the process of removing an unsatisfying consequence following a desirable behavior to increase the likelihood of that behavior being repeated. For example, a basketball coach who constantly criticizes his players about their technique while shooting free throws but then quiets down after seeing a player use proper technique is using negative reinforcement. Again, both positive and negative reinforcement serve to increase the likelihood that a behavior will be repeated. In the latter example, the coach is reinforcing the correct technique by eliminating his verbal criticism following an attempt with the correct technique.

Table 1 Four Response Consequences

Table 1 Four Response Consequences

The two response consequences that aim to decrease the likelihood that an undesired behavior will be repeated are punishment and extinction. Punishment refers to the process of introducing an unsatisfying consequence following an undesired behavior to decrease the likelihood of that behavior being repeated. For example, a coach who criticizes an athlete for making an error is implementing punishment in an effort to reduce the likelihood that the athlete will commit that error again. Extinction refers to the process of removing a satisfying consequence following an undesired behavior to decrease the likelihood of that behavior being repeated. A coach who intentionally ignores an athlete’s undesirable attention-seeking behaviors could be looking to extinguish those behaviors. The possibility also exists, however, that a coach who ignores a player’s extra hustle during practice may be (inadvertently) extinguishing that desired behavior. Both punishment and extinction serve to decrease the likelihood that a behavior will be repeated.

These examples focused on response consequences in sport, but these response consequences can be observed in many other contexts of human movement. For example, in exercise settings, a personal trainer might try to increase a client’s exercise behavior by praising her adherence to an exercise prescription (i.e., positive reinforcement) or by eliminating comments about a person’s excess weight after workouts (i.e., negative reinforcement). Alternatively, a physical therapist could reduce a patient’s compliance with an at-home rehabilitation prescription by ceasing to recognize the patient’s progress or effort (i.e., extinction) or by making an ill-advised criticism of the person’s ability during a rehabilitation appointment (i.e., punishment).

The Natural Frequency of Response Consequences in Sport

Little is known about the frequency of different response consequences in exercise, but the frequency of response consequences in sport has been examined. One classic study of coaching observed legendary UCLA basketball coach John Wooden over the course of 15 practices. These practices totaled 30 hours of coaching and 2,326 codable coaching behaviors. The coding scheme used in this study was derived from educational research and modified after some preliminary observations of Coach Wooden but it was not designed specifically to study response consequences. Surprisingly, positive reinforcement was relatively rare in this study, with approximately 8% of the coded behaviors classified as “praises” (6.9%) and “nonverbal rewards” (1.2%). Punishment was, fortunately, also relatively rare with only 6.6% of the coded behaviors classified as “scolds” (or “reproofs” as Coach Wooden preferred to call them). Another

8% of the coded behaviors were classified as “Woodens”—a sequence in which a scold or reproof was followed immediately by a demonstration of how to perform a behavior correctly, a demonstration of how the player performed a behavior, and a repeated demonstration of how the player should perform a behavior. This combination was consistent with Coach Wooden’s tendency to emphasize instructional comments (50.3%) and demonstrations (4.4%) in his coaching. Only trace amounts of “nonverbal punishment” were observed. None of the coding categories captured negative reinforcement or extinction, but that finding likely reflects the difficulty of capturing the absence of behavior using behavior observation methods. The behaviors exhibited by Coach Wooden while coaching an elite college basketball team may not generalize to all sport contexts.

A subsequent line of studies on youth sport developed a system for coding the observed behaviors of youth sport coaches that sheds light on operant conditioning processes in the context of youth sport. The Coaching Behavior Assessment System (CBAS) divides behaviors into (a) reactions to athlete behavior and (b) spontaneous actions (e.g., organizational activity, general communication). The responses to athlete actions are the most relevant to operant conditioning processes and include responses to desirable athlete behaviors, responses to athlete mistakes, and responses to athlete misbehaviors. The responses to desirable athlete behaviors include positive reinforcement and nonreinforcement, which can be linked to extinction processes in an operant conditioning framework. The responses to athlete mistakes include punishment and punitive technical instruction as well as mistake-contingent technical instruction, mistake-contingent encouragement, and ignoring mistakes. The first two of these responses might be described as punishment in the operant conditioning sense. Responses to athlete misbehaviors involve keeping control and may involve an element of punishment depending on the eliciting event.

Across studies of youth baseball, basketball, and swimming, positive reinforcement is consistently one of the most common behaviors observed by trained coders and perceived by young athletes. In contrast, punishment and punitive technical instruction are among the most infrequent behaviors observed by trained coders and perceived by young athletes. Unfortunately, even trace amounts of punishment can have devastating motivational consequences for young athletes’ motivation, anxiety, and self-perceptions. Another significant finding from this work was that a brief educational training program with a self-monitoring component can lead coaches to use more reinforcement and less punishment.

In sum, the frequency of response consequences in sport varies as a function of the competitive level of the participants. Youth sport coaches tend to use high levels of positive reinforcement and only infrequent punishment, but those proportions may change at different competitive levels. In the youth sport context, even trace amounts of punishment can have detrimental effects on youth development.

Motivational Implications of External Rewards

An interesting debate early in the 20th century centered on the question of whether external rewards might actually harm intrinsic motivation and reduce the likelihood that a behavior will be repeated. From an operant conditioning perspective, external rewards for a behavior should increase the odds that it will be repeated (i.e., positive reinforcement); however, considerable evidence that challenged this view had accumulated by the end of the 1990s. In a now-classic meta-analysis, researchers summarized studies that assessed intrinsic motivation as either people’s free-choice behavior (i.e., did they select the behavior absent any external pressure?) or people’s self-reported interest in a behavior. On average, results were consistent with the proposition that external rewards reduce future intrinsic motivation regardless of which measure was used; however, closer inspection of the results revealed some important nuances in the data.

The inhibiting effects of external rewards were limited to certain types of external rewards and specifically those rewards that were expected and tangible with one of three task-related contingency structures. First, external rewards that were contingent on a person’s mere engagement in the activity reduced intrinsic motivation for desired behaviors. This reward structure is relatively common in sport. For example, the custom of giving out “free” T-shirts to runners who register for a race is an engagement-contingent expected tangible reward. Second, external rewards that are contingent on a person completing an activity reduced intrinsic motivation for that activity. Many youth sport programs implement this type of reward by distributing participation awards, such as trophies or certificates, at the end of a sport season. Finally, external rewards that were contingent on a person’s level of performance reduced free choice of the desired behaviors, although these rewards appear to have no effect on people’s interest in the behavior. These performance-contingent rewards are pervasive in sport (e.g., medals to the top three finishers in the Olympics, trophies to tournament champions and runners-up).

This meta-analysis also revealed two important exceptions to the general conclusion that external rewards reduce intrinsic motivation for a behavior. First, unexpected external tangible rewards have no effect on intrinsic motivation. Second, one particular type of external reward, verbal praise, actually has the opposite effect and enhances intrinsic motivation for a stimulus behavior. This finding helps to reconcile two competing views on the effects of a popular response consequence. When the reward is verbal praise, behaviorists are correct that positive reinforcement should increase the likelihood that a behavior will be repeated. When the reward is an expected tangible reward that is somehow contingent on the task, the reward will actually serve to reduce intrinsic motivation (what behaviorists might describe as extinction).

Mechanisms Underlying the Effects of External Rewards

Two general explanations have emerged to account for the differential effects of rewards on intrinsic motivation and behavior. Cognitive evaluation theory (CET) posits that the effects of rewards depend on whether the rewards assume informational or controlling properties. When people construe rewards as providing feedback on the level of their performance, the informational properties of the reward should help to satisfy people’s need for competence and therefore boost intrinsic motivation. On the other hand, when the expectation of an external reward becomes the reason for one’s behavior, the reward is said to have assumed controlling properties (i.e., the rewards become the reason for the behavior). These controlling properties are thought to interfere with or thwart people’s need to feel autonomous (i.e., like the origins of their behavior) and therefore reduce intrinsic motivation.

A complementary explanation posits that expected tangible rewards undermine the intrinsic value of activities. Recent research has shown that, after training with a task under a performance contingent expected tangible reward structure, people display less free choice behavior when the reward is withdrawn. This reduction in intrinsic motivation corresponds with reduced activation in the striatum and midbrain—regions associated with task valuation. These findings indicate that performance-contingent expected tangible rewards undermine intrinsic motivation by reducing the value that people associate with the task.

Conclusion

In sum, reinforcement and punishment are simple behaviors with complex consequences. They may be used effectively to modify behavior but should be selected carefully to avoid unwanted long-term consequences. Considerably less is known about negative reinforcement and extinction processes in sport, exercise, and rehabilitation contexts.

References:

- Deci, E., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A metaanalytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 627–668.

- Gallimore, R., & Tharp, R. (2004). What a coach can teach a teacher, 1975–2004: Reflections and reanalysis of John Wooden’s teaching practices. The Sport Psychologist, 18, 119–137.

- Murayama, K., Matsumoto, M., Izuma, K., & Matsumoto, K. (2011). Neural basis of the undermining effect of monetary reward on intrinsic motivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 107, 20911–20916.

- Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Oxford, UK: Macmillan.

- Smith, R. E., & Smoll, F. L. (1997). Coaching the coaches: Youth sports as a scientific and applied behavioral setting. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 6, 16–21.

- Thorndike, E. L. (1901). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. Psychological Review Monograph Supplement, 2, 1–109.

See also: