The theory of planned behavior, developed by Icek Ajzen, is a social cognitive theory that has guided a large majority of theory-based research on physical activity. The theory of planned behavior is an extension of the theory of reasoned action developed by Martin Fishbein and Icek Ajzen in 1975. Since its introduction over 25 years ago, the theory of planned behavior has become one of the most frequently cited and influential models for predicting human behavior.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

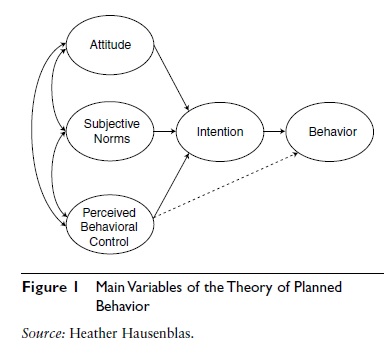

The theory of planned behavior specifies that some or all of the following four main psychological variables influence our behavior: intention, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. The combination of an individual’s expectations about performing a behavior and the value attached to that behavior form the conceptual basis of this theory. Figure 1 displays the main variables of the theory of planned behavior, and each of these main variables is described in more detail below. Figure 1 Main Variables of the Theory of Planned Behavior

Figure 1 Main Variables of the Theory of Planned Behavior

Theory of Planned Behavior Variables

Intention to perform a behavior is the central determinant of whether or not an individual engages in that behavior. Intention is reflected in a person’s willingness and how much effort that individual is planning to exert to perform the behavior. The stronger a one’s intention to perform a behavior, the more likely one will be to engage in that behavior. Thus, if someone has a strong intent to go for a walk this afternoon, that person is likely to go for that walk.

As might be expected, a person’s intention can weaken over time. The longer the time between intention and behavior, the greater the likelihood that unforeseen events will produce changes in people’s intention. For example, a young adult may intend to be a regular lifetime runner. However, after running for a few years, this person may become bored with the activity and start to swim instead. The runner did not expect boredom to affect the intention to run. A person’s behavioral intentions are influenced by personal attitudes about the behavior, the perceived social pressures to perform the behavior (subjective norm), and the amount of perceived control over performing the behavior (perceived behavioral control).

Attitude represents an individual’s positive or negative evaluation of performing a behavior. Do you find regular exercise useless or useful, harmful or beneficial, boring or interesting? An older adult may have a negative attitude toward engaging in a vigorous physical activity such as running, but rather have a positive attitude toward walking in the neighborhood. Our attitude toward a specific behavior is a function of our behavioral beliefs, which refer to the perceived consequences of carrying out a specific action and our evaluation of each of these consequences. A college student’s beliefs about playing doubles tennis could be represented by both positive expectations (e.g., it will improve my social life because I will meet lots of people) and negative expectations (e.g., it will reduce my time to study). In shaping a physical activity behavior, the person evaluates the consequences attached to each of these beliefs. Common behavioral beliefs for physical activity include that it improves fitness or health, improves physical appearance, is fun and enjoyable, increases social interactions, and improves psychological health.

Subjective norm reflects the perceived social pressure that individuals feel to perform or not perform a behavior. Subjective norm is believed to be a function of normative beliefs, which are determined by the perceived expectations of important significant others, such as family, friends, physician, or priest, or groups like classmates, teammates, or church members, and by the individual’s motivation to comply with the expectations of these important significant others. For example, an individual may feel that his wife thinks he should exercise three times a week. The husband, however, may not be inclined to act according to these perceived beliefs. Common normative beliefs for physical activity include those of family members, friends, and health care professionals.

Perceived behavioral control represents the perceived ease or difficulty of performing a behavior. Perceived behavioral control influences behavior either directly or indirectly through intention. People may hold positive attitudes toward a behavior and believe that important others would approve of their behavior. However, they are not likely to form a strong intention to perform that behavior if they believe they do not have either the resources or opportunities to do so. You may have a positive attitude and enjoy swimming; however, if you do not have access to a pool you will not be able to perform this behavior.

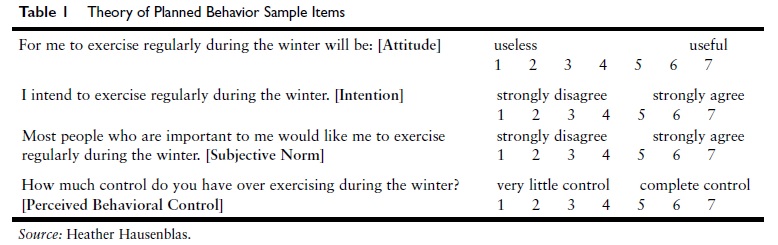

Perceived behavioral control is a function of control beliefs. Control beliefs represent the perceived presence or absence of required resources and opportunities (e.g., there is a road race this weekend), the anticipated obstacles or impediments to behavior (e.g., probability of rain on the weekend is 90%), and the perceived power of a particular control factor to facilitate or inhibit performance of the behavior (e.g., even if it rains this weekend, I can still participate in the road race). The most common control beliefs for physical activity include lack of time, lack of energy, and lack of motivation. Table 1 contains sample items for measuring the theory of planned behavior constructs in relation to regularly exercising during the winter.

Theory of Planned Behavior and Physical Activity Research

Several meta-analytic reviews have supported the theory of planned behavior for explaining and predicting a wide variety of physical activities in a wide variety of populations, including ethnic minorities, youth, pregnant women, cancer patients, diabetic adults, cancer survivors, and older adults. In general, researchers found that intention is the strongest determinant of behavior followed closely by perceived behavioral control. And our intention to perform a behavior is largely influenced by our attitude and perceived behavioral control followed to a lesser extent by subjective norm. It is important to note that the influence of each of the theory of planned behavior construct can vary from population and context.

Table 1 Theory of Planned Behavior Sample Items

Table 1 Theory of Planned Behavior Sample Items

Elicitation Studies

A main strength of the theory of planned behavior is that an elicitation study forms the basis for developing questions to assess the theory’s variables in a specific population. The elicitation study enables a practitioner to determine the specific beliefs for a specific population. This is very important because we know that beliefs vary by population and even by activity. For example, the main behavioral beliefs for breast cancers survivors are that exercise gets my mind off cancer and treatment, makes me feel better, improves my well-being, and helps me maintain a normal lifestyle. In comparison, the main behavioral beliefs for pregnant women are related to pregnancy-specific issues such as having a healthier pregnancy and easier labor and delivery.

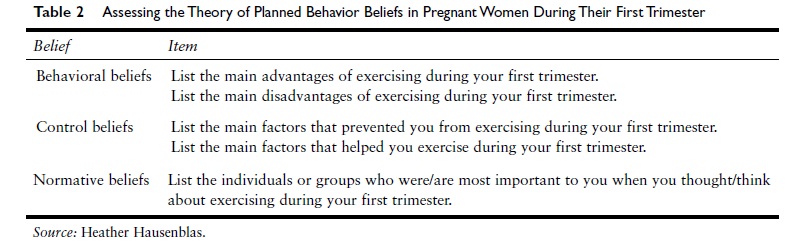

Because beliefs vary by population, researchers and practitioners are encouraged to refer to research that has determined the physical activity beliefs of their specific intervention population, for example postpartum women, cancer survivors, or high school students. If physical activity beliefs for a practitioner’s population of interest have not been determined, then it is recommended that an elicitation study be conducted to determine the pertinent beliefs concerning a behavior for that specific population. Table 2 provides an example of open-ended items used to assess the beliefs of pregnant women during their first trimester. Women during their first trimester would be asked to list three to five responses for each of the items. Then a content analysis (a simple frequency count) to determine which beliefs are most salient and finally a structured belief questionnaire would be developed from the content analysis (see Table 2).

Structured items that arise from the elicitation study should be specific to the target at which the behavior is directed, the action or specificity of the behavior under study, and the context and time in which the behavior is being performed. For example, when developing a walking intervention for older adults, the practitioner should ask a sample of older adults to list the main advantages of walking briskly three times a week for 30 minutes outside during the summer. This information will help researchers develop an intervention based on the salient behavioral beliefs of these older adults that is specific to the behavior. According to the theory of planned behavior, once beliefs are modified, intention will be altered and the desired behavior change will occur. The relative contribution of the theory of planned behavior constructs may fluctuate from context to context. Thus, before interventions using this framework are implemented, the predictive ability of these constructs with the specific population and specific context should first be tested.

Using Theory for Practice

The theory of planned behavior is useful in identifying psychosocial determinants of physical activity. Therefore, it has been useful for developing community, group, and individual exercise programs. For example, people intend to exercise when they hold a positive evaluation of exercise. Exercise programs that offer a positive experience would likely increase intention to exercise, which would likely positively influence exercise behavior. Positive behavioral beliefs and their evaluation may be enhanced if people are given experiences with enjoyable types of physical activities and then gradually encouraged to increase the intensity, duration, and frequency of those activities. Perceived behavioral control is an important factor in intention to be physically active. When individuals perceive physical activity as difficult to do, intention is low. Assisting people to overcome barriers, such as time involvement, other obligations, or feelings of inability, should enhance perceptions of control about carrying out exercise. We will now take a closer look at a physical activity intervention called Wheeling Walks that was guided by the theory of planned behavior.

Table 2 Assessing the Theory of Planned Behavior Beliefs in Pregnant Women During Their First Trimester

Wheeling Walks was an 8-week mass media walking campaign developed by Bill Reger et al. (2001). The main goal of the intervention was to promote walking among sedentary adults ages 50 to 65 years old in the city of Wheeling, West Virginia. This “communication intervention used the theory of planned behavior . . . constructs to change behavior by promoting 30 min[utes] of daily walking through paid media, public relations, and public health activities.” The impact of the campaign “was determined by pre and post-intervention telephone surveys with 719 adults in the intervention community and 753 adults in the comparison community and observations of walkers at 10 community sites” (p. 285).

To develop the messages to be used in the intervention, the theory of planned behavior was used to determine the salient beliefs that should be targeted during the walking intervention. They found that sedentary and irregularly active people shared similar attitude and subjective norm beliefs with regular exercisers but showed very strong differences on perceived control. Sedentary adults believed that they had less control over their time and scheduling of exercise compared to regular exercisers. Wheeling Walks promoted 30 minutes or more of moderate intensity walking on almost every day for better health and feeling more energetic. To address, the I-don’t-have-time belief, which was identified as a primary barrier to physical activity, the ads suggested “start walking ten minutes a day at first, then twenty minutes . . .” and also compared the 30-minute time period to that of “one TV program.” Each ad ended with the tagline, “Isn’t it time you started walking” (p. 287).

Behavioral observation showed a 23% increase in the number of walkers in the intervention community versus no change in the comparison community. They also found that 32% of the baseline sedentary population in the intervention community reported meeting the physical activity guidelines by walking at least 30 minutes at least 5 times per week versus 18% in the comparison community. An important question is how long did the increased walking last by the adults in Wheeling, and can these results be replicated in other communities. The answer to both questions is yes. A follow-up study revealed that the campaign succeeded in sustaining the increase in walking 12 months after the intervention. As well, the campaign has been successfully replicated in other communities including rural and larger communities.

Theory Limitations

Although the theory of planned behavior has been successful in explaining and predicting physical activity behavior, limitations of the theory exist. Some researchers reject the theory of planned behavior outright as an adequate explanation of human social behavior. Most critics, however, accept the theory’s basic assumptions but either question its sufficiency or inquire into its limiting conditions. Some of the theory’s potential limitations are briefly discussed below.

First, factors such as personality, affect or mood, demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, socioeconomic status), past exercise behavior, and habit are not directly taken into consideration within the theory of planned behavior. This is a limitation because researchers examining the determinants of physical activity have consistently found, for example, that the percentage of the population reporting no physical activity is higher among female than male populations, among older adults than younger adults, among extraverts than neurotics, and among the less affluent than the more affluent.

Second, there is ambiguity regarding how to define perceived behavioral control, and this creates measurement problems. Ajzen stated that the term perceived behavioral control may be misleading and to avoid misunderstanding, he suggested that perceived behavioral control should be read as “perceived control over performance of a behavior.” Ajzen further noted that perceived behavioral control is composed of two components: self-efficacy (ease or difficulty of performing the behavior) and controllability (beliefs about the extent to which performing the behavior is up to the actor); and thus, measures of perceived behavioral control should contain items that assess both self-efficacy and controllability. Third, the longer the time interval between intention and behavior, the less likely the behavior will occur. Research reveals that the predictive power of intention will vary inversely with the time between the measurement of intention and performance of the behavior. The longer the time interval between intention and behavior, the more likely intention is to change with new available information. As time passes, an increasing number of intervening events can change people’s behavioral, normative, or control beliefs and can modify attitudes, subjective norms, or perceptions of control, thus generating revised intentions. Changes of this kind will tend to reduce the predictive validity of intentions that were assessed before the changes took place. This new information would result in a diminished relationship between intention and behavior. Consistent with this argument, shorter intervals between assessment of intentions and behavior are associated with stronger correlations than are longer time intervals.

A fourth potential limitation pertains to the construct of subjective norm. Consistent throughout the physical activity literature, the theory of planned behavior variables of attitude and perceived behavioral control have been significant predictors of intention. Subjective norm, however, is generally a weaker predictor of intention. One reason for the inconsistent usefulness of subjective norm is that the role of significant others may not be important in encouraging participation of physically active individuals. Support for this view comes from the fact that subjective norm is a stronger predictor of intention for other health behaviors, such as contraceptive use, where the role of significant others is deemed to be more important for the decisions made, and thus cannot be ignored.

Conclusion

Changing people’s behavior is very difficult to do, especially when dealing with a complex health behavior such as physical activity. To increase the success of predicting, understanding, explaining, and changing physical activity behavior, researchers and practitioners should use a theoretical framework such as the theory of planned behavior as a guide. Researchers have found support for the utility of attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and to a lesser extent, subjective norms in explaining people’s intention to becoming physically active. Also, researchers have found a strong relationship between someone’s intention to be active and one’s engaging in the behavior. Of importance, the size of the intention–behavior effect shrinks significantly when past exercise behavior is controlled. Furthermore, a person’s perception of the personal control over engaging in physical activity can also directly predict behavior. In general, there is strong evidence that the theory of planned behavior can explain and predict people’s physical activity intentions and behaviors. In summary, because of the success of the theory of planned behavior to explain and predict exercise behavior, intervention research reveals that it is also a useful framework to guide physical activity interventions.

References:

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action-control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11–39). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

- Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health, 26, 1113–1127. Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Bélanger, L. J., Plotnikoff, R. C., Clark, A. M., & Courneya, K. S. (2012). Determinants of physical activity in young adult cancer survivors. American Journal of Health Behavior, 36, 483–494.

- Hausenblas, H. A., Giacobbi, P., Cook, B., Rhodes, R. E., & Cruz, A. (2011). Prospective examination of pregnant and nonpregnant women’s physical activity beliefs and behaviours. Journal of Infant and Reproductive Psychology, 29, 308–319.

- Plotnikoff, R. C., Lippke, S., Courneya, K., Birkett, N., & Sigal, R. (2010). Physical activity and diabetes: An application of the theory of planned behavior to explain physical activity for Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes in an adult population sample. Psychology and Health, 25, 7–23.

- Reger, B., Cooper, L., Booth-Butterfield, S., Smith, H., Bauman, A., Wootan, M., et al. (2001). Wheeling walks: A community campaign using paid media to encourage walking among sedentary older adults. Preventive Medicine, 35, 285–292.

- Rhodes, R. E., Blanchard, C. M., Courneya, K. S., & Plotnikoff, R. C. (2009). Identifying belief-based targets for the promotion of leisure-time walking. Health Education Behavior, 36, 381–393.

- Symons Downs, D., & Hausenblas, H. A. (2005). Elicitation studies and the theory of planned behavior: A systematic review of exercise beliefs. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 6, 1–31.

- Symons Downs, D., & Hausenblas, H. A. (2005). The theories of reasoned action and planned behavior applied to exercise: A meta-analytic update. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 2, 76–97.

See also: