Traditional approaches to helping individuals change health behaviors focus on reflective processes. In other words, in these approaches, the first thing a practitioner might do is identify what a client thinks about a behavior. Thus, initial counseling may focus on increasing positive beliefs and perceived benefits associated with that behavior and challenging less positive beliefs. Support may turn to building confidence to initiate and then maintain the behavioral change.

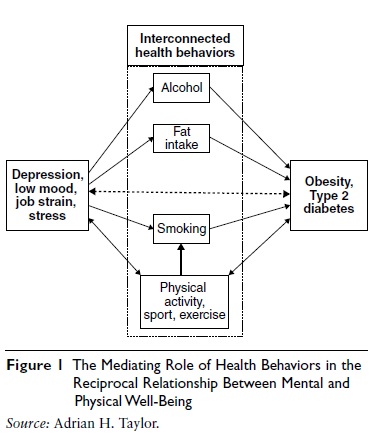

Less directive approaches, such as those involved in motivational interviewing, may give the individual greater freedom to identify which behavior to work on, but again, the approach usually focuses on separate behaviors with an emphasis on working through cognitions about that behavior. Given that people often have a cluster of poor lifestyle behaviors, the challenge emerges to identify how best to help clients with changing multiple health behaviors, as shown in Figure 1.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Debate may follow in epidemiology about the risk associated with each behavior, and thus which to focus on first. Also, specialist health promotion counselors may focus on physical activity (PA) while others focus on smoking cessation or diet. Besides being inefficient, trying to change multiple behaviors using multiple but parallel or distinct counseling approaches can lead to cognitive overload and perhaps multiple failure. Yet, so far, theory and practice remain primarily oriented toward understanding and changing single health behaviors.

Figure 1 The Mediating Role of Health Behaviors in the Reciprocal Relationship Between Mental and Physical Well-Being

Figure 1 The Mediating Role of Health Behaviors in the Reciprocal Relationship Between Mental and Physical Well-Being

There is, however, increasing interest in developing new theories and guidance for practitioners to help clients with multiple behavior change, as discussed by James O. Prochaska. Not only does Figure 1 show how different lifestyles may mediate the reciprocal relationship between mental and physical health but it also highlights that there are complex interrelationships between these different behaviors. For example, surveys suggest that more active people tend to also drink less alcohol, eat fewer snacks, and smoke less. The relationships are not always so straightforward: Some types of sports participation are associated with fewer healthy lifestyles than others.

The next question is whether engagement in PA prevents the reduction of healthy lifestyles, and, if it does, how? What changes as a result of playing sport or regularly exercising that discourages smoking, excessive alcohol use, or poor diet? Likewise, do sedentary lifestyles, common in Westernized society, lead to other less healthy lifestyles and why? If we know the answers to these questions, this may help us develop PA interventions that impact on multiple health behaviors. These questions are relevant not only in the context of engaging young people in sport and PA but also for adults who already have clusters of poor lifestyles.

There is evidence that more physically active children and adolescents are less likely to progress to smoking, taking illicit drugs, drinking alcohol excessively, and engaging in antisocial behavior.

However, it is difficult to produce strong causal evidence, as there may be a number of confounding variables. Nevertheless, there may be plausible psychological mechanisms, such as enhanced self efficacy, self-perceptions, and self-esteem, and enhanced mood from PA. Excessive sedentary behavior in adolescence may lead to deactivation and fatigue, which may lead to turning to high-energy food and other substances to enhance mood.

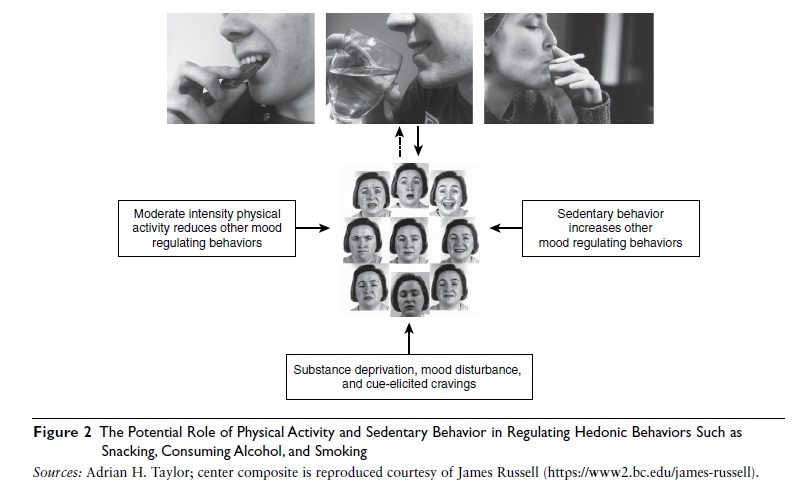

Much more is known about whether PA (of various doses) causally influences engagement in other behaviors among adults, and especially smoking and snacking. Neuroscience and cognitive psychology have greatly advanced our understanding of addictive processes involved in both these behaviors in particular. Common areas of the brain are activated in anticipation of a reward or reinforcement, when faced with cues or images associated with the behavior. As Figure 2 shows, with the circumplex model of affect at the center, when people are deprived of a substance (regularly used to regulate mood), or feel under pressure (with low mood) or view cues associated with the behavior (e.g., a cigarette pack, a picture of someone else smoking), this generates a state of wanting. By smoking or snacking, a reward is received and a sense of pleasure (on the horizontal axis of the model) or increased activation (on the vertical axis of the model) is experienced.

Figure 2 The Potential Role of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Regulating Hedonic Behaviors Such as Snacking, Consuming Alcohol, and Smoking

Figure 2 The Potential Role of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Regulating Hedonic Behaviors Such as Snacking, Consuming Alcohol, and Smoking

A great deal of evidence has been accumulating over the past 30 years on the acute and chronic effects of exercise on mood and affect. Briefly, moderate-intensity exercise increases affective activation and pleasure. Recently, work has turned to also understanding the effects on urges, desire, and cravings for various substances such as nicotine and high-energy snack food. Researchers have discovered that even a 15-minute brisk walk (that most people can achieve throughout a typical day) reduces substance cravings, attentional bias to salient images, ad libitum smoking and snacking, during temporary abstinence, under stress and in the presence of salient cues. Brain-imaging studies have shown reduced activation in areas of the brain associated with viewing smoking-related images, after exercise compared with rest. With these studies in mind, new counseling interventions have been developed to encourage smokers to use PA as an aid to reducing and quitting smoking. Given that self-regulation of snacking and smoking and other health behaviors is a challenge, and these behaviors are often driven by automated rather than reflective mental processes, promoting PA appears to have a role in enhancing the self regulation of multiple behaviors, irrespective of whether there is an intention not to smoke or eat high-energy snack food.

References:

- Oh, H., & Taylor, A. H. (2012). Brisk walking reduces ad libitum chocolate snacking in breaks between both low and high demanding cognitive tasks. Appetite, 58, 387–392.

- Prochaska, J. O. (2008). Multiple health behavior research represents the future of preventive medicine. Preventive Medicine, 46, 281–285.

- Taylor, A. H. (2010). Physical activity and depression in obesity. In C. Bouchard & P. T. Katzmarzyk (Eds.), Physical activity and obesity (pp. 295–298). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Taylor, A. H., Everson-Hock, E. S., & Ussher, M. (2010). Integrating the promotion of physical activity within a smoking cessation programme: Findings from collaborative action research in UK Stop Smoking Services. BMC Health Services Research, 10,

- Taylor, A. H., & Ussher, M. (in press). Physical activity as an aid in smoking cessation. In P. Ekkekakis (Ed.), The Routledge handbook on physical activity and mental health. New York: Routledge.

See also: