The association of being at home with feelings of increased physical comfort, safety, and psychological well-being are reflected in a wealth of popular expressions and sayings, such as Home free; Home is where the heart is; East–west, home is best; Home sweet home; There’s no place like home. Thus, it is hardly surprising that the term home advantage has been adopted in sport to represent two related phenomena—both of which are founded on the belief that a team’s own park, stadia, or venue is, indeed, a good place in which to compete.

One phenomenon pertains to (for lack of a better term) competition location. In most professional sports in North America, for example, teams play a full schedule of regular season games to determine final league standings. Those teams ranking higher in the final standings are awarded one extra competition in their home venue in every 3-, 5-, or 7-game playoff series. That extra opportunity to compete at home is referred to as a home advantage (e.g., “New York will have the home advantage in its playoff series against Boston”). If the team happens to lose one of its extra competitions at home, it is said to have lost its home advantage. Although competition location can represent a home advantage, it does not always turn out to provide that advantage. For example, in the first round of the National Hockey League (NHL) playoffs in 2010, home teams won 22 games and lost 27 games; in 2011, they won 23 games and lost 26 games. So, certainly from the perspective of competition location, home teams in those 2 years were not able to capitalize on their home advantage.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

A second phenomenon, flowing directly from the first, pertains to probability for a successful outcome. In almost every instance where large sets of data have been examined—for team and individual sports, for female and male competitors, for international competitions between nations, for athletes and teams from across the age and experience spectrum—the home competitors have had a superior winning percentage that is beyond chance (discussion of these findings in the section that follows).

During the 2011–2012 NHL season, ice-hockey fans closely followed the Detroit Red Wings as they obtained an exceptional 75.6% success rate at home. In their 41 home games, they won an NHL-high of 31, including a league-record 23 straight. This success rate is atypical, of course, but does serve to illustrate an exceptional instance of home advantage.

In this entry, discussion of the home advantage phenomenon is limited to results pertaining to an increased probability for a successful outcome. To this end, discussion is focused on the extent of the home advantage in team and individual sports over a variety of contexts and the explanations that have been advanced by fans, the media, athletes, and sport scientists to help explain its causes. Also, the implications of competing at home for the psychological states and behaviors of athletes and coaches are examined.

The Extent of the Home Advantage

In almost every sport examined, teams have better results when they compete at home. In professional sport, for example, over a recent 5-year period, the winning percentage was 53.7% in baseball, 61.0% in English football (soccer), 54.6% in ice hockey, 58.2% in American football, and 61.0% in basketball.

In most sports examined, athletes competing individually also have superior results when they compete in their home territory. For example, in World Cup Alpine Skiing, skiers competing in their home country on average improved 16% from where they were seeded going into the race to where they actually finished. Interestingly, professional golf and tennis are the only two individual sports where a home advantage has not been found.

In terms of international competitions, there also seems to be evidence of a home advantage for host countries in both the Summer and Winter Olympic Games, as well as the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (International Federation of Association Football; FIFA) World Cup. In the case of the Winter Olympics, for example, host countries showed an average improvement of about four medals over the previous Olympiad. The only host country in the history of the Winter Olympics that failed to improve was Italy (in Torino in 2006); it won 11 medals compared to 13 in Salt Lake City in 2002.

In the case of the Summer Olympics, host nations show an average improvement of approximately five medals over their previous Olympiad. This respectable improvement, however, is dwarfed by China’s performance in the 2008 Summer Olympics held in Beijing; China improved its medal count by 37 (for a total of 100 medals) from Athens in 2004.

The FIFA World Cup has also yielded results that seem to show that host nations benefit from competing at home. The first World Cup took place in Uruguay in 1930 and there have been 19 competitions every 4 years since; the most recent World Cup was in 2010 in South Africa. There were no tournaments in 1942 and 1946. The host nation has reached the semi-finals in 12 of 19 tournaments, the finals in 8 of 19 tournaments, and has won 6 out of 19 times. (Given that FIFA is now making an effort to provide a host opportunity to countries and regions that based on their world rankings have minimal chance of winning a medal [e.g., United States, 1994; South Africa, 2010], the overall results are impressive from a home advantage perspective.) The six host countries that have won the FIFA World Cup include Uruguay (1930), Italy (1934), England (1966), West Germany (1974), Argentina (1978), and France (1998). The runners-up include Brazil (1950) and Sweden (1958). Finally, Chile (1962), Italy (1990), and Germany (2006) all finished third when they hosted.

Causes of Home Advantage: Popular Beliefs

The benefits that accrue to host teams have given rise to considerable discussion, speculation, and inquiries among fans, athletes, media, and coaches about why. What are the principal factors that underlie the home advantage? As might be expected, there is some overlap among the groups in the explanations advanced.

For example, crowd support was the first choice of fans in one survey and one of the top three choices advanced in another conducted with intercollegiate athletes. Two other choices (endorsed by athletes) were familiarity with the home court and the elimination of the need to travel. The belief that greater familiarity with the nuances of the home venue provides home competitors with the major source of their advantage also was the top reason advanced by coaches.

After working for years as a sabermetrician in major league baseball (sabermetrics is the specialized study of baseball through objective statistics), Craig Wright, with the assistance of Tom House, a major league pitching coach, offered his appraisal. Wright and House estimated that 5% of the home advantage is due to a psychological lift from the crowd, 5% results from the advantage of batting last, 10% is due to familiarity with the stadium, 10% is due to the ability of the home team to select and use personnel best suited to its home stadium, 30% is due to a regime regularity, and 40% is due to an umpire bias that favors the home team.

Causes of Home Advantage: Empirical Analyses

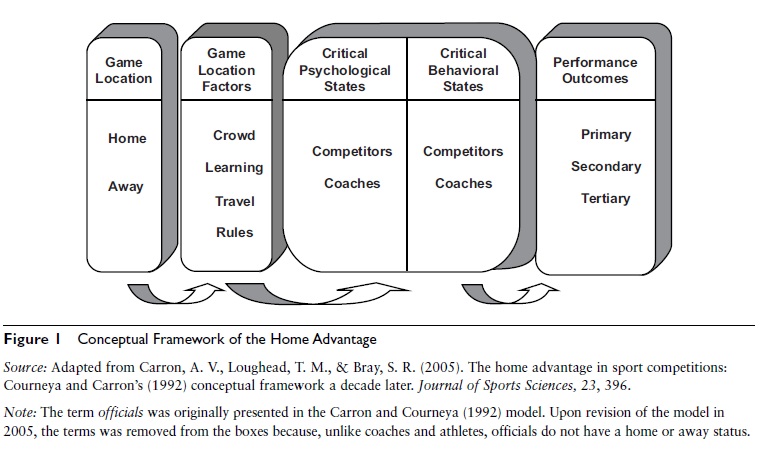

Figure 1 is a framework Albert Carron, Todd M. Loughead, and Steven R. Bray offered to systematically examine the home advantage. As a starting point, they proposed that the location of the competition (home vs. away) differentially influences four main factors—the degree of crowd support (and through crowd support, possible favorable officiating decisions), the need to travel, learned familiarity with the venue, and some rule advantages (e.g., batting last in baseball).

Figure 1 Conceptual Framework of the Home Advantage

Game Location Factors

As is the case with many areas of scientific inquiry, results from studies examining the nuances of each of the game location factors have been consistent in some cases but have shown mixed results in the case of other factors. For example, studies that have examined the influence of the rules factor have been consistent; the home team does not have an advantage from the rules.

Insofar as crowd support is concerned, the results have been mixed. At the risk of oversimplification, the following generalizations seem reasonable:

- Absolute crowd size is generally unrelated to the home advantage.

- Crowd density is consistently positively related to the home advantage.

- The nature of crowd behavior (i.e., booing versus cheering the home team) has no consistent influence on the home advantage.

- Laboratory studies have shown that the home crowd has an influence on officiating decisions (i.e., home teams receive more favorable calls). However, field studies and archival research have not supported these results. In well controlled studies, there is no evidence that crowd support produces more favorable officiating for the home team.

The need for a visiting team to travel to compete has also received a great deal of research attention. Again, the results are mixed. At the risk of oversimplification, the following generalizations seem reasonable:

- Distance traveled (e.g., a 120-mile trip to compete versus a 100-mile trip to compete) does not influence the visiting team’s disadvantage (and, of course, the home team’s advantage).

- The duration of the road trip does not influence the visiting team’s disadvantage in professional basketball and baseball. In professional ice hockey, visiting teams are less successful in the initial games of a road trip.

- Travel across time zones can be a source of disadvantage for visiting teams. The adage “traveling west is best” does seem to have some validity. Professional teams traveling from western to eastern regions of North America are at a greater disadvantage than teams traveling from the east westward.

The final game location factor in the framework illustrated in Figure 1 is the home team’s learned familiarity with its own venue. There are a number of elements that fall under this category; these can be categorized as either stable or unstable. The latter are elements in the home team’s environment that can be manipulated to one’s own advantage. For example, anecdotal accounts in the media have reported a professional baseball team competing at home providing excess water to the base paths to reduce the speed advantage possessed by the visiting team. Another reported a visiting professional basketball coach’s concern that the home team might overly inflate the balls to facilitate a higher dribble that would favors the preferences of its point guard.

Stable elements are idiosyncratic aspects of the home team’s venue. The Green Monster in Boston’s Fenway Park would be one example. Presumably Boston outfielders, as a result of their greater opportunities to practice and play in that environment, would be more familiar with caroms. As another example, professional ice-hockey teams competing on an ice surface at home that is smaller or larger than the league average could benefit from increased familiarity.

The following generalizations about the role that familiarity might play in the home advantage seem reasonable:

- Professional soccer teams with a playing surface larger or smaller than the league average have a greater home advantage.

- Professional baseball teams with artificial turf have a greater home advantage than those teams without artificial turf.

- Professional baseball, basketball, and ice-hockey teams moving to a new facility (thereby temporarily losing their superior knowledge of their own venue) experience a reduction in their home advantage. This result is moderated by team quality. Teams with a superior home advantage prior to relocation (a home advantage greater than 50%) experience a temporary significant reduction. Conversely, teams with an inferior home advantage prior to relocation (a home advantage less than 50%) have a temporary significant improvement in their home advantage.

As Figure 1 illustrates, the game location factors are thought to contribute to different critical psychological states for the home versus visiting athletes and coaches.

Critical Psychological and Physiological States

There is relatively consistent evidence that supports the conclusion that coach and athlete psychological states are superior when playing at home. The generalizations that seem reasonable are as follows:

- Both athletes and coaches have greater personal confidence and confidence in their team prior to competitions at their home venue.

- Athlete emotions and mood states are superior at home. For example, cognitive and somatic anxiety, depression, tension, anger, and confusion are lower prior to a home competition.

- Athletes feel more vulnerable at competitions held away from home because they know they will have to deal with the taunting of away fans (commonly seen in basketball).

Critical Behavioral States

As Figure 1 illustrates, competing at home versus away is also thought to have a differential influence on the behaviors of home versus visiting athletes and coaches. A sense of territoriality, which refers to an animal’s occupation and defense of a geographical area where it feeds, nests, and mates, has been used to explain the home advantage. Athletes do have higher levels of testosterone prior to home competitions. They are thought to compete more aggressively, expend more effort, and persist longer.

The studies that have been carried out comparing athlete and coach behaviors at home versus away contribute to the following generalizations:

- From a strategy and tactics point of view, coaches adopt more defensive tactics for away games and more aggressive strategies for home games.

- Home versus away teams do not differ in defensive behaviors, such as errors, shots blocked in basketball, or double plays in baseball, but home teams do exhibit more aggressive offensive behaviors like shots taken in ice hockey and basketball.

- Home and visiting teams do not differ in number of aggressive penalties, such as penalties that have intent to injure, as their critical component.

- Studies have found trends that away teams seem to be penalized more often and home teams get away with more. In addition, star players seem to get away with more at home.

Conclusion

The aspect of group territoriality known as the home advantage has undoubtedly been one of the most examined phenomena in the sport context by coaches, athletes, researchers, administrators, and consultants alike. Generally speaking, the home advantage seems to share some consistency in prevalence across all sport types. Although it would be fair to say that while the home advantage is enjoyed throughout all sport, it is not necessarily enjoyed by all teams within those sports. Certain factors like team quality do moderate the effects of the home advantage. Additionally, it is likely fair to assume that questions going forward surrounding the home advantage would not be to determine whether such a phenomenon exists; as outlined in this entry, the pervasive evidence demonstrating a superior winning percentage for the home team goes beyond chance. The fact that the home advantage has also been well documented over the last 100 years should calm any uncertainties. Future directions on investigating the home advantage should maintain a primary focus on why this phenomenon continues.

The conceptual framework presented in this entry is intended as a useful guide to further investigation. No claim is made, however, that it encapsulates everything and all factors pertaining to the home advantage. What it does provide is a simple depiction of what is presumably a dynamic construct (in that it fluctuates) depending on a wide variety of variables and factors specific for each sport and each team.

References:

- Balmer, N. J., Nevill, A. M., & Williams, A. M. (2001). Home advantage in the Winter Olympics (1908–1998). Journal of Sports Sciences, 19, 129–139.

- Balmer, N. J., Nevill, A. M., & Williams, A. M. (2003). Modelling home advantage in the Summer Olympic Games. Journal of Sports Sciences, 21, 469–478.

- Carron, A. V., & Eys, M. A. (2012). Group dynamics in sport (4th ed.). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Carron, A. V., Loughead, T. M., & Bray, S. R. (2005). The home advantage in sport competitions: The Courneya & Carron conceptual framework a decade later. Journal of Sport Sciences, 23, 395–407.

- Courneya, K. S., & Carron, A. V. (1992). The home advantage in sport competitions: A literature review. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 14, 13–27.

- Pollard, R., & Pollard, G. (2005). Long-term trends in home advantage in professional team sports in North America and England (1876–2003). Journal of Sport Sciences, 23, 337–350.

See also: