The prescreening, in-depth exploration, and choice (PIC) model, proposed by Gati and Asher in 2001, provides a practical systematic framework for making career decisions based on decision theory. The PIC model consists of three stages: (1) prescreening the potential set of career alternatives to locate a small and thus manageable set of promising alternatives; (2) in-depth exploration of the promising alternatives, resulting in a list of a few suitable alternatives; (3) choice of the most compatible alternative, based on a detailed comparison between the suitable alternatives.

Theoretical Background

Decision theory has been regarded as a potential frame of reference for career decision making for almost half a century. This perspective conceptualizes career choices in terms of the cognitive processes used to locate the career alternatives most compatible with the individual’s preferences and capabilities. Career decision making is a complex task. The number and variety of alternatives is often very large, and many attributes (e.g., traveling, teamwork) are required for adequately describing the potential alternatives and the individual’s characteristics. Therefore, comparing among the alternatives and evaluating their compatibility to the individual is a nontrivial task.

The Three Types of Decision-Making Models

Three types of decision-making models have commonly been cited as potential theoretical frameworks for the career decision-making process. Normative models specify procedures for making optimal rational decisions, aimed at maximizing the subjective (expected) utility, based on an overall evaluation of the alternatives. Descriptive models focus on characterizing the ways individuals actually make decisions in real life and document biases and inconsistencies in individuals’ natural decision behaviors that lead to less than optimal decisions.

Prescriptive decision models bridge the theoretically oriented normative models and the reality-oriented descriptive ones by providing a systematic framework for decision making while taking into account individuals’ bounded rationality and intuitive thinking. Since it translates theoretical knowledge from decision theory into career counseling interventions, this type of model appears the most relevant for facilitating career decision making. The PIC model is a prescriptive model that outlines a systematic and practical framework for making career decisions.

The Three Stages of the PIC model

The PIC model aims at reducing the complexity of career decision making by separating the process into three distinct stages, each focusing on a well-defined task: prescreening, in-depth exploration, and choice.

Prescreening the Potential Alternatives

The goal of the prescreening stage is to deal with the overload of information in career decision making by helping the individual focus on the most relevant information. The goal is to locate a manageable set of promising alternatives that deserve further, in-depth exploration, using sequential elimination. The idea of sequential elimination is based on Tversky’s 1972 elimination-by-aspects model, which has been shown to be compatible with the intuitive ways individuals make decisions when faced with a large array of alternatives.

The search for promising alternatives is based on the individuals’ preferences in career-related aspects that are most important to them. Career-related aspects are all variables that can be used to characterize either individuals’ preferences and abilities or career alternatives. The list of important aspects that should guide the prescreening process includes objective constraints (e.g., disability), competencies (e.g., creativity, technical skills), and core preferences (e.g., teamwork). The model distinguishes among three facets of the individual’s preferences: (1) the importance of the aspect, (2) the level regarded as optimal (e.g., “only outdoors”), and (3) additional, less desirable but still acceptable level(s), representing the individual’s willingness to compromise (e.g., “mainly outdoors”).

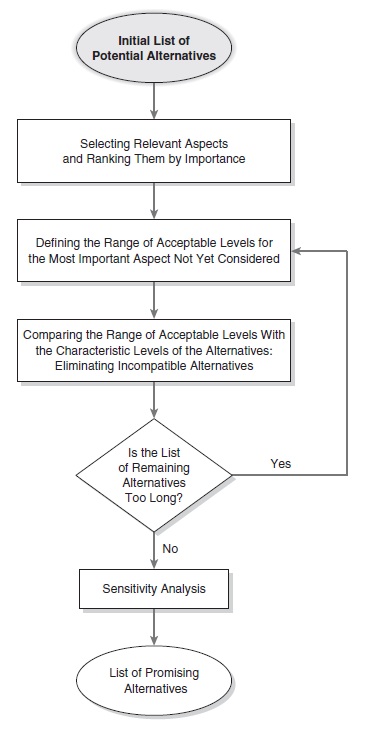

The process of sequential elimination is a within-aspect, across-alternatives search: It is conducted aspect by aspect, starting from the most important one. For each aspect, the characteristics of all potential alternatives are compared with the individual’s preferences, and incompatible alternatives are eliminated. The process is repeated for the remaining aspects in descending order of importance until the number of remaining promising alternatives is manageable (i.e., seven or less). To decrease the possibility that potentially suitable alternatives might be eliminated because of a minor mismatch, the prescreening stage ends with a reexamination of the effects of potential changes in the individual’s inputs on the outcome—the list of promising career options; this process is called sensitivity analysis. These steps are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The steps of the prescreening stage

Source: Adapted with author’s permission from Figure 1 in Gati, I. (1986). Making career decisions: A sequential elimination approach. Journal of Counseling, 33, 408—U7. Copyright by the American Psychological Association.

In Depth Exploration of the Promising Alternatives

The goal of this stage is to confirm that a promising alternative is indeed suitable for the individual. During this stage, the analysis focuses on a within-occupation, across-aspect evaluation. This involves zooming in on one promising alternative at a time and collecting additional, comprehensive information on it to find out (a) whether the occupation is indeed compatible with the individual’s preferences, (b) whether the individual is willing and able to satisfy the demands involving the essence of the occupation (i.e., its core aspects, e.g., physical treatment of people and working in shifts for a paramedic), and (c) the probability of actualizing that choice, taking into account the prerequisites of the occupation and the requirements for success in it. During this in-depth exploration, some promising alternatives will be eliminated, and thus this stage will end in a short list of suitable alternatives.

Choice

The goal of this stage is to choose a few most suitable alternatives, rank ordered by priority of implementation. It involves a refined, detailed comparison between the alternatives under consideration, focusing on the differences among them. The small number of alternatives still relevant at this stage makes it possible to use the principles of rational normative models, and in particular the principle of compensation (i.e., trade-offs between the advantages and disadvantages of each alternative). The process that can be advocated is based on comparing pairs of alternatives from the short list of final options. It involves canceling out the relative advantages of the compared alternatives in each pair until the decision maker remains with only the net advantages of one of the alternatives. This process is repeated until only one alternative remains. Finally, the congruence between the outcome of the systematic decision process and previously intuitively appealing occupational alternatives should be examined: it may strengthen the individual’s confidence in the choice or indicate the need for a reexamination of the decision process in order to locate the sources for incompatibilities and try to reconcile them.

Research Findings

Research has supported the rationale underlying the PIC model and its descriptive validity. It has shown that individuals’ information-seeking behavior is compatible with the stages of the PIC model. Specifically, when faced with a large array of career options, people tend to use a small number of significant criteria, one at a time, to reduce the number of alternatives to a few; but when faced with a small number of alternatives, people can compare them using compensatory principles. Interventions based on the PIC model, such as MBCD (an Internet-based career planning system; ), has demonstrated its effectiveness: (a) decreasing individuals’ career decision-making difficulties, (b) helping them advance toward making a decision, and (c) increasing the probability of greater occupational satisfaction in the future.

Using the PIC Model in Career Guidance and Counseling

The role of career counselors includes guiding clients through the stages of the decision-making process while encouraging them to play an active and dominant role in each stage. During prescreening, career counselors should help clients explicate their preferences (and their willingness to compromise, if needed), and take notice of actual or perceived constraints. During the in-depth exploration, counselors should direct clients to relevant sources of information, highlighting the quality of various sources in terms of accuracy and biases. During the choice stage the counselor can assist the client through the complex task of evaluating the suitable alternatives. Finally, counselors can guide clients in exploring ways to increase the probability of actualizing the most preferred alternative. The PIC model can serve as a framework for a dynamic counselor-client dialogue as well as for monitoring the client’s advancement in the process. In addition, PIC can serve as a blueprint for designing computer-assisted career guidance systems, such as MBCD.

Future Directions

Dealing with career indecision has long been a focus of theory and research, and helping clients to overcome their indecision is among the core roles of career counseling. The PIC model demonstrates the potential in adopting decision theories for designing interventions aimed at fulfilling that role. However, there is still a need to reinforce the mutual enrichment between theoretical knowledge about decision making and the hands-on experience of career counselors. Future efforts to combine the normative and descriptive models for career decisions are likely to yield a more comprehensive prescriptive approach for facilitating the career decision-making process. The challenge is to design systematic guidelines that allow adaptive and active career decision making in the face of uncertainty, fuzziness, and change that characterize the 21st century’s world of work.

References:

- Gati, I. (1986). Making career decisions: A sequential elimination approach. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33, 408-U7.

- Gati, I., & Asher, I. (2001). The PIC model for career decision making: Prescreening, in-depth exploration, and choice. In F. T. L. Leong & A. Barak (Eds.), Contemporary models in vocational psychology (pp. 7-54). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Gati, I., & Asher, I. (2001). Prescreening, in-depth exploration, and choice: From decision theory to career counseling practice. Career Development Quarterly, 50, 140-157.

- Gati, I., Gadassi, R., & Shemesh, N. (2006). The predictive validity of a computer-assisted career decision-making system: A six-year follow-up. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 205-219.

- Gati, I., & Tal, S. (2008). Decision-making models and career guidance. In J. Athanasou & R. Van Esbroeck (Eds.), International handbook of career guidance (pp. 157-185). Berlin, Germany: Springer.

See also: