Gestalt theory was one of the major schools of psychology of the first half of the twentieth century. While its main early focus was a protest against the atomism or elementism that characterized its rival schools (such as structuralism and functionalism and, later, behaviorism), its emphasis on the organized, integrated nature of psychological entities and processes has continued to influence the field throughout the remainder of the century. The German word Gestalt, roughly meaning “structure,” “whole,” “form,” or “configuration,” has no exact equivalent in English, so the term has become part of the technical vocabulary of psychology.

Gestalt theory was one of the major schools of psychology of the first half of the twentieth century. While its main early focus was a protest against the atomism or elementism that characterized its rival schools (such as structuralism and functionalism and, later, behaviorism), its emphasis on the organized, integrated nature of psychological entities and processes has continued to influence the field throughout the remainder of the century. The German word Gestalt, roughly meaning “structure,” “whole,” “form,” or “configuration,” has no exact equivalent in English, so the term has become part of the technical vocabulary of psychology.

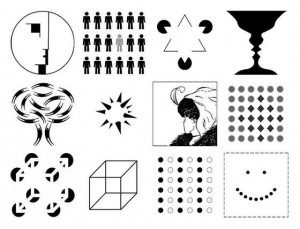

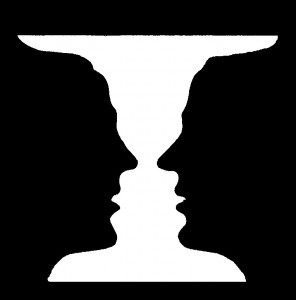

Gestalt psychologists rejected the “constancy hypothesis” that was generally taken for granted early in the twentieth century, namely that there is a constant point-for-point correspondence between physical characteristics of a stimulus and the psychological attributes of the resulting sensation. In numerous experiments they demonstrated that local perceptual qualities vary not just with the local stimulus but with the contexts that surround the stimulus. Percepts are not immutable correlates of the local physical stimuli that give rise to them, but reflect specific interactive relational aspects of a stimulus complex. The well-known perceptual constancies (size, shape, color, brightness, etc.) are all inconsistent with the “constancy hypothesis”: for example. the perceived brightness of a small spot in a large visual field depends upon not only the light intensity of the spot itself but also the intensity of the spot’s surround. Comparably, color contrast phenomena disprove the “constancy hypothesis”; the same gray circle will appear greenish if surrounded by violet, or yellow if surrounded by blue. Perceptual attributes such as size, shape, color, brightness, movement, etc., are relationally determined.

Relational determination also plays a crucial role in many cognitive (and physiological) functions other than sensation and perception. While it is central in perceptual organization (as in controlling what aspects of a complex sensory input will be perceived as figure and which as ground), it is also at the core of productive thinking. To solve a problem productively, it is necessary to understand what aspects of it are essential and which superficial or irrelevant, as well as the critical interrelations among the core aspects. In most psychological wholes or Gestalten the parts are not indifferent to each other, but are mutually interdependent; indeed the attributes of the separate component parts of the Gestalt are determined by their place, role, and function within the whole of which they are parts. Productive thinking involves transforming a confused, fuzzy, meaningless view of a problem into a clear conception of it that takes all the relevant features into account; such reorganization or restructuring of the problem results in insight, understanding, and its solution, if the reorganization is adequate to the central features of the problem.

This view of problem solving, and of learning, contrasted sharply, in its emphasis on meaningfulness, with the views of learning that prevailed in other schools, which instead emphasized blind contiguity in space and time (as in traditional associationism and as in the process of classical conditioning that was considered prototypic of learning by behaviorists). The top-down approach of the Gestalt theorists, making the whole primary, was the opposite of the bottom-up approach typical of psychologists in other schools, which began with “elements” (such as sensations. or stimuli and responses) and studied how they combine to add up to a whole.

The Gestalt psychologists contrasted their “dynamic” view with what they called the static “machine theory” of their opponents. Natural systems—in physics and physiology as well as in psychology—undergo “dynamic self-distribution,” as in electrical or magnetic fields, such that the organization of any Gestalt or whole will be as “good” as the prevailing conditions allow. This “principle of Pragnanz,” as the Gestalt psychologists called it, makes unnecessary the arbitrary connections or mechanical constraints that “andsum” theorists use in explaining natural processes in physics, physiology, and psychology: consider the form of a soap bubble or of a drop of oil in water; they are the result not of an artificial constraining mold but of dynamic self-distribution.

Antecedents of Gestalt Psychology

That a whole may be more than a mere sum of its parts had been recognized since antiquity, even by Plato. During the nineteenth century several philosophers emphasized that a thoroughgoing simple elementism is inadequate. For example, John Stuart Mill objected to his father James Mill’s theory of mind as the sum total of sensations and images associated via contiguity in space and time. He argued that the properties of chemical compounds may not be deducible from the properties of their constituent elements in isolation, and proposed a “mental chemistry” in contrast with his father’s “mental mechanics.” Even Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt, one of whose objectives was to analyze the contents of consciousness into their constituent “mental elements,” had been compelled to acknowledge that mental compounds may display emergent qualities that are not to be found in their constituent elements in isolation—a result that he proposed is due to a principle of “creative synthesis” that characterizes human mental processes.

That a whole may be more than a mere sum of its parts had been recognized since antiquity, even by Plato. During the nineteenth century several philosophers emphasized that a thoroughgoing simple elementism is inadequate. For example, John Stuart Mill objected to his father James Mill’s theory of mind as the sum total of sensations and images associated via contiguity in space and time. He argued that the properties of chemical compounds may not be deducible from the properties of their constituent elements in isolation, and proposed a “mental chemistry” in contrast with his father’s “mental mechanics.” Even Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt, one of whose objectives was to analyze the contents of consciousness into their constituent “mental elements,” had been compelled to acknowledge that mental compounds may display emergent qualities that are not to be found in their constituent elements in isolation—a result that he proposed is due to a principle of “creative synthesis” that characterizes human mental processes.

In 1890, Christian von Ehrenfels argued that “form qualities” such as squareness, circularity—or a melody—are separate elements over and above the component elements of a whole. Thus a square is, in effect, the sum of four equal straight lines plus four right angles—plus the “Gestalt quality” of “squareness,” The lengths of the lines or their color can be changed, but this will not alter the squareness of the square; you can transpose a melody into a different key, changing every note, yet the melody remains unchanged. He proposed that it is the transposability of Gestalt qualities, their independence of the specific qualities of the other elements, that is the criterion for their existence.

The Emergence of Gestalt Theory

In 1910 Max Wertheimer pointed out that the “primitive” music of a tribe in Ceylon had a complex structure, in which early parts of a melody set up requirements for the melody’s continuation. Two years later (1912a) he analyzed examples of numerical thinking in aboriginal peoples that is not purely summative but that takes into account the dynamic and structural features of the problem to which the numerical thinking is applied. For example, if one divides a chain of eight links in half one has two chains of four links each: another division yields four sets of two links each: but with yet another division there no longer is a chain. In certain situations “one, a couple, a few, many” is an appropriate quantitative scale: and no reasonable person would specify an amount of rice in terms of the number of kernels it contains.

Structural and dynamic features take precedence over “elements” and their “andsums.” It is not appropriate to think of wholes as the sum total of their parts, or, as in von Ehrenfels’s case, as “more” than the sum total of their parts (the “elemental parts” plus the element of “Gestalt quality”). Rather, wholes are entirely different from any summation; they have their own inherent properties that in turn determine the nature of the parts. There is no need to refer to “elements.” whether they be in the form of James Mill’s elementism, Wundt’s product of creative synthesis, or Ehrenfels’s constituent elements plus form quality.

Another 1912 article by Max Wertheimer (1912b) on the perception of apparent movement is generally viewed as the founding publication of the Gestalt school (see Ash, 1995. for a thorough account of the emergence of the Gestalt school of psychology in Germany). When two adjacent stationary visual stimuli are presented successively under appropriate spatial and temporal conditions, the result is a compelling perception not of two successively presented stationary stimuli nor of two simultaneously presented ones, but of a single object moving from one location to another. The Gestalt of the entire exposure is such that the perceived motion is entirely different from the characteristics of the two sensations in isolation, and no combination of “elements” can explain the percept; it is totally different from any “sum” of its “parts.” This demonstration also convincingly disproved the “constancy hypothesis” of an immutable relation between stimulus and sensation; the motion is in the percept but nowhere in the stimuli. The whole, the Gestalt, had become primary perceptually and ontogenetically.

Wolfgang Kohler and Kurt Koffka were among the participants in Wertheimer’s experiments on apparent motion. They joined Wertheimer in promoting Gestalt psychology during the ensuing decades.

Major Proponents and Landmarks of Gestalt Psychology

Wertheimer, Kohler, and Koffka are generally viewed as the three original Gestalt theorists. All of them had been students of Carl Stumpf at Berlin, and had been influenced by Stumpf’s holism and his advocacy of the phenomenological method in experimental psychology. Erich Moritz von Hornbostel was an early advocate of the school. but went on to devote himself primarily to ethnomusicology. Kurt Lewin, younger than the three founders, broadened the Gestalt approach into a somewhat looser “field theory” and applied it to motivation, personality, and social psychology. Gestalt psychologists of the second generation include the following: Rudolf Arnheim applied the theory to the psychology of art. Karl Duncker performed experiments on problem solving using verbal protocols. His experimental work on induced motion established that if an object and its surrounding environment move relative to each other the movement is perceived as occurring in the object rather than in the frame. Hans Wallach did extensive experimental work primarily in perception. Solomon E. Asch, in addition to experiments in perception, association, and personality. developed a Gestalt perspective on social psychology. Abraham S. Luchins performed experiments on the debilitating effects of set on problem solving. George Katona’s work on organizing and memorizing summarized experiments demonstrating the superiority of Gestalt-based meaningful learning over rote memorization. He later became a pioneer in the new discipline of psychological economics. Mary Henle, an experimental psychologist, published significant papers on the nature and history of the Gestalt approach and prepared several anthologies of Gestalt work. Wolfgang Metzger promulgated the Gestalt perspective in Germany after the three founders had emigrated to the United States.

Wertheimer, Kohler, and Koffka are generally viewed as the three original Gestalt theorists. All of them had been students of Carl Stumpf at Berlin, and had been influenced by Stumpf’s holism and his advocacy of the phenomenological method in experimental psychology. Erich Moritz von Hornbostel was an early advocate of the school. but went on to devote himself primarily to ethnomusicology. Kurt Lewin, younger than the three founders, broadened the Gestalt approach into a somewhat looser “field theory” and applied it to motivation, personality, and social psychology. Gestalt psychologists of the second generation include the following: Rudolf Arnheim applied the theory to the psychology of art. Karl Duncker performed experiments on problem solving using verbal protocols. His experimental work on induced motion established that if an object and its surrounding environment move relative to each other the movement is perceived as occurring in the object rather than in the frame. Hans Wallach did extensive experimental work primarily in perception. Solomon E. Asch, in addition to experiments in perception, association, and personality. developed a Gestalt perspective on social psychology. Abraham S. Luchins performed experiments on the debilitating effects of set on problem solving. George Katona’s work on organizing and memorizing summarized experiments demonstrating the superiority of Gestalt-based meaningful learning over rote memorization. He later became a pioneer in the new discipline of psychological economics. Mary Henle, an experimental psychologist, published significant papers on the nature and history of the Gestalt approach and prepared several anthologies of Gestalt work. Wolfgang Metzger promulgated the Gestalt perspective in Germany after the three founders had emigrated to the United States.

Soon the Gestalt school expanded its perspective into almost all subfields of psychology. During the 1920s Wertheimer published articles with many examples of productive thinking, and also wrote on how the principle of Pragnanz results in the organized perception of integrated objects in the world through the operation of the principles of perceptual organization. Koffka applied the Gestalt perspective to the psychology of mental development. Kohler reported pioneering studies of problem solving in chimpanzees, demonstrating their capacity for meaningful insight; experiments on transposition that generated international interest; and detailed explorations of the implications of the Gestalt approach in physics, biology, chemistry, and physiology. During the 1930s and later, Kohler published a number of books on Gestalt psychology that were to become world renowned; Koffka wrote a mid-1930s major text on Gestalt theory summarizing its experimental foundations and developing systematic theoretical positions about most of the significant psychological issues of the time. Wertheimer’s posthumous book on productive thinking was published in the 1940s. Condensed English translations of significant Gestalt publications were made available by Willis D. Ellis in 1938 (and reissued thereafter). Wertheimer’s book on productive thinking was reissued in 1959, 1978, and 1982, and translated into several foreign languages. German translations of Wertheimer’s late essays on truth, ethics, freedom, and democracy were prepared during the 1990s. An international multidisciplinary quarterly journal, Gestalt Theory, the official journal of the Society for Gestalt Theory and Its Applications, has been published by Westdeutscher Verlag in Wiesbaden, Germany, since 1979. Although all the first, and most of the second, generation of Gestalt psychologists had died, Gestalt theory continued to be highly visible.

By the end of the twentieth century, Gestalt thought was evident in a wide array of contemporary research. The Gestalt work on productive thinking was frequently viewed as posing challenging problems for cognitive psychology (e.g., Murray, 1995; Sternberg & Davidson, 1995), and the early experimental work on the perceptual constancies, on the perception of movement, and on the organization of perception continued to interest visual physiologists and cognitive neuroscientists (e.g., Rock & Palmer, 1990; Spillmann & Ehrenstein, 1996). Writers on social psychology, personality, and psychopathology continued to use a Gestalt perspective, some explicitly and many implicitly. A Gestalt orientation continued to permeate a significant number of theoretical and empirical approaches in almost all areas of psychology.

Bibliography:

- Ash, M, C. (1995), Gestalt psychology in German culture, 1890-1967: Holism and the quest for objectivity, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ellis, W. D. (1967). A source book of Gestalt psychology. New York: Harcourt, Brace. (Original work published 1938)

- Koffka. K. (1935). Principles of Gestalt psychology. New York: Harcourt. Brace.

- Murray, D. J. (1995). Gestalt psychology and the cognitive revolution. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Rock. I., & Palmer. S. (1990). The legacy of Gestalt psychology. Scientific American, 263 (6), 84-90.

- Spillmann, L., & Ehrenstein, W. H, (1996). From neuron to Gestalt. In R. Greger. & V, Windhorst (Eds.). Comprehensive human physiology: Mechanisms of visual perception (Vol. i. pp. 861-893), Heidelberg: Springer.

- Sternberg. R. J., & Davidson. J. E. (Eds.). (1995). The nature of insight. Cambridge. MA: Bradford/MIT Press.

- von Ehrenfels. C. (1890). Uber Gestaltqualitaten [On Gestalt qualities]. Vierteljahresschrift fur wissenschaftliche Philosophic. 14, 249-292.

- Wertheimer. M. (1910). Musik der Wedda [The music of the Veddas]. Sammelbunde der internationalen Musikgesellschaft, it. 300-309.

- Wertheimer. M. (1912a). Uber das Denken der Natur-volker 1. Zahlen und Zahlgebilde [On the thinking of aboriginal people: 1. Numbers and numerical concepts]. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie, 60. 321-378.

- Wertheimer. M. (1912b). Experimentelle Studien fiber das Sehen von Bewegung [Experimental studies of the perception of movement]. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie, 61. 161-265.

- Wertheimer. M. (1982). Productive thinking. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1945)