Assimilation refers to the integration of one culture into another. This integration may include changes in cultural characteristics such as language, appearance, food, music, and religion among other customs. Cultural values and beliefs also influence this integration of cultures. Assimilation is relevant to sport performance in that sports occur in the context of culture, society, and politics. In addition, each sport has its own culture and characteristics that may reflect or be in contrast with the values and beliefs of society and the individual athletes that play a particular sport. As such, an athlete’s cultural milieu may interact with that of the sport and society in which the sport occurs to influence performance. For instance, a sport that focuses on individual performance and recognition may not fit well for an athlete from a culture that emphasizes teamwork and humility.

Assimilation may influence the type of sport an athlete selects and the roles assumed within sports and may also manifest in interactions and relationships with teammates and coaches. Typically, cultural assimilation involves an underrepresented (minority) group integrating into a dominant group’s culture. An athlete from rural American Samoa playing American football at an urban college in the United States, for example, might integrate into the dominant cultural group of the city in which he plays by adopting the cultural practices of that region. However, the preceding example and description represent a unidirectional and oversimplified version of the concept of assimilation, as they suggest that assimilation necessarily occurs in the direction of the dominant group and that it is a linear process of change. Assimilation can also occur from the direction of the dominant to the underrepresented group, though this is less common. For example, a White athlete playing American football at a predominantly Black college may assimilate toward the culture of his fellow students, campus, and teammates, which may not reflect the dominant culture per se. Moreover, assimilation is not a process that is linear with a finite endpoint of being assimilated; rather it is a process that is constantly evolving. Individual athletes may assimilate to varying degrees based on situational, historical, and other factors. Thus, a Cuban immigrant playing professional baseball may be less assimilated around other Cuban or Latin American teammates or coaches, whereas he may be more assimilated around teammates and coaches from other cultures. In other words, assimilation is an evolving process that may be state dependent and also reflect the evolution of an athlete’s assimilation.

The way in which assimilation is initiated may also affect how it is perceived, thereby influencing the athlete in negative or positive aspects or both. Assimilation may occur voluntarily or involuntarily: A soccer player from North Africa may be traded to a team in Russia, with little control over the decision. In contrast, another athlete may decide to immerse himself or herself in a culturally different environment to expand life experience. The perceived level of control over assimilation may affect how an athlete responds to it.

Enculturation and Acculturation

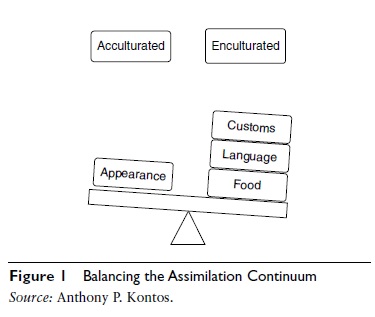

Regardless of the mechanism for assimilation, there are two primary components to assimilation: (1) enculturation, or the level to which someone adheres to primary cultural beliefs, values, and customs, and (2) acculturation, or the level to which someone adopts dominant or other cultural beliefs, values, and customs. One might think of complete enculturation and acculturation as extreme endpoints on a balancing continuum (see Figure 1). Most athletes’ assimilation will balance between some percentage of acculturation and enculturation that together equals 100%; for example, 75% enculturated, 25% acculturated. This percentage is based on which side the cultural characteristics discussed earlier reside. An athlete’s assimilation balance may shift based on the situation and may change over time to reflect life experiences.

Effects of Assimilation

Assimilation can sometimes result in acculturative stress (stress related to adapting to another culture) and may adversely affect performance in sport. In extreme cases, if not addressed, acculturative stress may develop into depression, anxiety, or hostility. These negative effects of assimilation may be more salient for athletes who are highly acculturated and then return to their own culture. When athletes return to their own culture, they may be perceived as having sold out their own culture for the dominant culture. In contrast, a recently immigrated athlete or one who is highly enculturated may struggle to adapt to a new culture and the athletes from that culture. As a result, such an athlete may be isolated in the new cultural environment. However, for some athletes assimilation may not play any role at all in creating stress or adversely affecting sport performance. For these athletes, assimilation may even help alleviate stress and anxiety by allowing them to fit in better and feel more comfortable in an unfamiliar culture.

Figure 1 Balancing the Assimilation Continuum

Conclusion

Assimilation is nonlinear and constantly evolving through both direct and indirect experiences with one’s own and other cultures. An athlete’s level of enculturation and acculturation occurs on a balanced continuum that may shift back and forth based on the situation and cultural context, as well as the evolution of the athlete’s assimilation process. It is important to point out that assimilation does not typically involve a purposeful integration of another culture. In fact, assimilation may simply occur as a product of direct or indirect exposure to and familiarity with another culture over time. As such, many athletes are unaware of how assimilated they are or of assimilation’s potential role on performance and sport. Therefore, assimilation should be viewed as neither positive nor negative but rather as an evolving process that is highly individualized for each athlete.

References:

- Kontos, A. P., & Arguello, E. (2009). Sport psychology consulting with Latin American athletes. In R. Schinke (Ed.), Contemporary sport psychology (pp. 181–196). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science.

- Kontos, A. P., & Breland-Noble, A. (2002). Racial/ethnic diversity in applied sport psychology: A multicultural introduction to working with athletes of color. The Sport Psychologist, 16, 296–315.

- Ryba, T. V., Schinke, R. J., & Tenenbaum, G. (2010). The cultural turn in sport psychology. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Schinke, R. J., & Hanrahan, S. J. (2009). Cultural sport psychology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

See also: