The iceberg profile in sport is a visual representation of desirable emotional health status, characterized by low raw scores on the tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion scales and above norms (the “water line”) on vigor as assessed by the Profile of Mood States (POMS). The iceberg profile as a metaphoric image has been employed for better understanding of emotion–performance relationships and well-being in competitive and high-level athletes. This entry examines the utility of the iceberg profile in description of interaction effects of multiple negative and positive mood states affecting preparation and athletic performance.

Iceberg Profile as a Metaphor

An iceberg (ice mountain, from Middle Dutch ijsberg; Norwegian isberg) is a large mass of ice floating in the sea. The iceberg image is often used metaphorically to represent the notion that only a very small amount (the tip) of information about a situation is available or visible whereas the real bulk of data is either unavailable or otherwise hidden. The principle gets its name from the fact that only about one tenth of an iceberg’s mass can be seen above the water’s surface, while about nine tenths of it is submerged and invisible. Another interesting feature of the iceberg profile, which should be emphasized, is its ability to identify the interactive effects of the components of different phenomena. That is why the iceberg profile as an image, principle, or a model is popular in various contexts. The iceberg diagram has also been helpful to identify some of the crucial aspects and influences in management and organizational settings. The iceberg graphically demonstrates the idea of having both visible and invisible structures interact. It is also helpful for understanding of global issues and is often used in systems thinking. In this case, at the tip above the water are events happening in the world; below the waterline there are often patterns or the recurrence of events. Patterns are important to identify because they indicate that an event is not an isolated incident. Like the different levels of an iceberg, deep beneath the patterns are the underlying structures or root causes that create or drive those patterns.

Profile of Mood States-Based Iceberg Profile in Sport

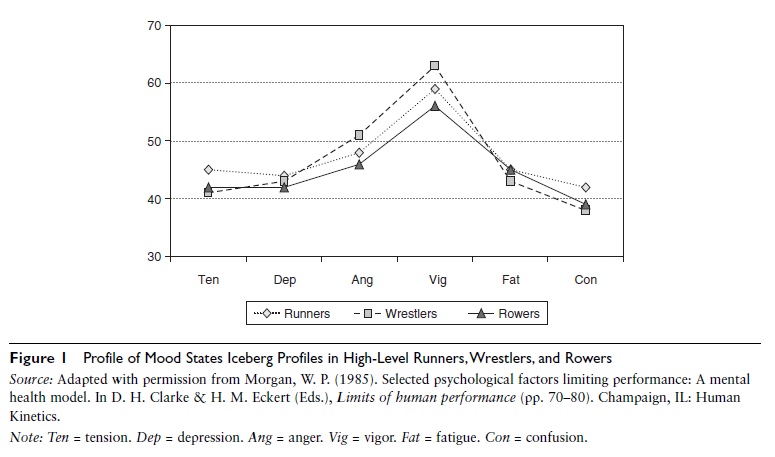

William Morgan introduced the term iceberg profile, as a metaphor, in sport in the late 1970s; it was based on his systematic research and monitoring of overtraining and staleness in competitive and elite athletes across different sports. In his assessments, Morgan used the 65-item POMS and noticed that elite athletes and active individuals in general tend to score below the population average on the tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion scales. Moreover, these individuals usually scored about one standard deviation above the population average on vigor. This profile has been called the iceberg profile because the resulting configuration resembled an iceberg. All five negative mood states fell below the population average (T-score of 50), and one positive mood state was one standard deviation above the population mean (see Figure 1). (It has been observed that it was good luck that the developers of the POMS placed the vigor subscale fortuitously in the middle, or there would be no iceberg profile at all!)

The POMS yields five negative mood states measures, one positive mood state, and a global measure of mood. A global score is computed by adding five negative mood states (tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion) and subtracting the one positive mood state (vigor). Since this computational procedure sometimes yields negative values a constant of 100 is added (Ten + Dep+ Ang + Fat + Con + 100 – Vig). These values are employed as a baseline for individual athletes (and in groups) to estimate the dynamics of staleness during the season. If the athlete suffers from chronic fatigue and is unable complete a workout session, his POMS profile can become inverted. The inverse iceberg profile is characterized by a lower level of vigor and higher levels of tension, depression, anger, fatigue, and confusion than the average individual. This type of mood profile is associated with a poor state of physical and mental functioning.

The POMS has several response sets depending on the focus in the assessment of mood states. These sets include statelike (right now, today, or prior to your last competition) and traitlike (generally, usually, typically during a week or a month) foci. For instance, if the athlete is asked to respond to the question “How have you been feeling during the past week, including today?” rather than “How have you been feeling today?” then both statelike and traitlike aspects of emotional state are assessed.

Iceberg Profile and Mental Health Model

The POMS-based iceberg profile represents visually the interaction of multiple mood states, and it is grounded in Morgan’s mental health model (MHM). Briefly described, the MHM assumes that performance is inversely correlated with psychopathology. Thus, positive mental health is associated with high performance levels whereas mood disturbances are predicted to result in performance decrements. The basic premise of the model is that positive aspects of mental health should be associated with broadly defined success in sport.

Figure 1 Profile of Mood States Iceberg Profiles in High-Level Runners,Wrestlers, and Rowers

Figure 1 Profile of Mood States Iceberg Profiles in High-Level Runners,Wrestlers, and Rowers

There are several concerns with the application of POMS-based iceberg profiles for testing thevalidity of the MHM in prediction of athletic performance, especially at the individual level. First, POMS emotion descriptors are predominantly negative (five negative versus one positive mood state). Second, the researcher-generated mood descriptors are “fixed” and thus do not capture the idiosyncratic nature of athletes’ individual emotional experiences. Third, POMS-based iceberg profiles as measures of mood states are not related directly to preperformance and mid-performance situations. Neither are they focused on optimal and dysfunctional impact of mood states on performance. Fourth, population average (norms) rather than individually optimal and dysfunctional profiles serve as criteria to evaluate post performance emotion impact. Finally, there is a need to examine the effectiveness of deliberately created iceberg profile based on other than POMS assessment measures—for instance, idiosyncratic emotion-centered and action-centered profiles.

Extension of Iceberg Profile Applications

The utility of POMS-based iceberg profiles can be enhanced by adding context-specific and relevant response sets. These response sets include recalled iceberg profiles of past emotional experiences (“How did you feel prior to your season best competition?”); anticipatory profiles (“How do you think you will feel prior to the upcoming competition?”); performance related (pre-, mid-, post-event) profiles; interpersonal profiles (“How do you feel while interacting with your coach or a teammate?”), and intragroup profiles (“How do you feel in this team and in your previous team?”).

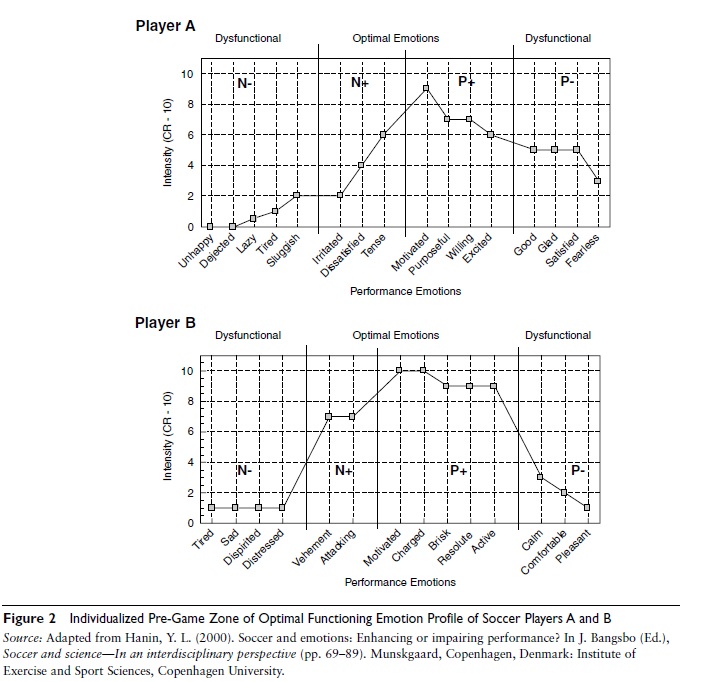

Iceberg profile applications can also be extended by the assessment of emotions other than POMS mood states. For instance, does the iceberg principle work for other multiple emotion measures, such as CSAI-2 (with self-confidence, cognitive and somatic anxiety) or the individualized emotion-centered profiling? Some of these concerns were addressed empirically in the individual zone of optimal functioning (IZOF) model that predicts high probability of individually successful performance if the intensity of athlete’s optimal pleasant (P+) and optimal unpleasant (N+) emotions interacts with low intensity of dysfunctional unpleasant (N–) and dysfunctional pleasant (P–) emotions. Figure 2 depicts two individualized iceberg profiles based on the assessment of personally relevant and performance-related idiosyncratic emotions. These iceberg profiles were constructed by deliberately placing optimal positively toned and negatively toned emotions in the middle and dysfunctional emotions (negative and positive) by their sides (N– >N+ and P+ >P–).

Individualized emotion-centered profiling captures the fact that one athlete may perform quite well when angry or anxious whereas another athlete with the same mood may perform poorly. That is why it is crucial to use task and personally relevant items (idiosyncratic emotion descriptors). In both cases, the predominance of functionally optimal positively toned and negatively toned emotions (P+N+) over the dysfunctional negatively toned and positively toned emotions (N–P–) serves as a predictor of high probability of individually successful performance (well functioning). On the other hand, predominance of positives (well-being P+P–) over the negatives (ill-being N+N–) characterizes the athlete’s situational mental health status. A distinction between well-being (vs. ill-being) and well-functioning (vs. ill-functioning) is made by identifying both positive and negative emotions that have optimal and dysfunctional impact on mental health and athletic performance.

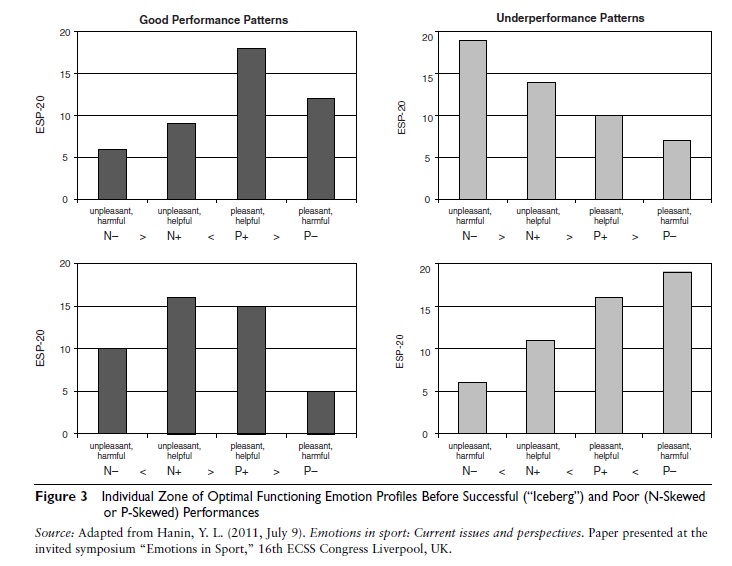

Variability of optimal intensity zones for each emotion descriptor and their interaction are identified during the repeated (recalled and current) assessments of emotion profiles prior to several successful performances in a single athlete. Prior to unsuccessful performance, the profiles are “flat” or positively skewed or negatively skewed. Consistent results suggest that there are two success-related and two failure-related iceberg profiles based on measures of multiple positively toned and negatively toned emotions. These four profiles are the summary of intraindividual emotion dynamics contrasting individually successful and unsuccessful performances (Figure 3).

Enhancing the Utility of Individualized Emotion Profiling

There are several ways to enhance the utility of the iceberg profile and its applications.

Figure 2 Individualized Pre-Game Zone of Optimal Functioning Emotion Profile of Soccer Players A and B

Figure 2 Individualized Pre-Game Zone of Optimal Functioning Emotion Profile of Soccer Players A and B

- “Ideal” emotion iceberg profiles should be identified by multiple intraindividual profiling of five to seven personally successful (self-referenced) performances.

- Emotion descriptors should be idiosyncratic and self-generated by the athlete rather than fixed researcher-generated markers

- To create iceberg profile, these multiple successrelated factors should be placed in the middle; poor performance factors are located by the sides.

- The main focus in research and applications should be on distinguishing intraindividually between the profiles related to success and poor performance.

- Action-centered profiling is also recommended in considering successful and unsuccessful performances processes.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that iceberg profile predicting successful performance is possible to create by using idiosyncratic athlete-generated and aggregated researcher-generated emotion descriptors. Successful performances are predicted by two predominant types of profiles (P+) or (P+N+) that are similar for most athletes even if they have different emotion markers. On the other hand, inverse (“flat,” “cavity-shape,” N-skewed, or P-skewed) iceberg profiles predict high probability of individually poor performances. A future challenge in sport psychology (SP) is the development of individualized emotion scales capable of capturing interactive effects of emotions on athletic performance. Iceberg profile provides a partial solution to this challenging task.

Figure 3 Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning Emotion Profiles Before Successful (“Iceberg”) and Poor (N-Skewed or P-Skewed) Performances

Figure 3 Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning Emotion Profiles Before Successful (“Iceberg”) and Poor (N-Skewed or P-Skewed) Performances

References:

- Hanin, J., & Hanina, M. (with commentators). (2009).Optimization of performance intop-level athletes: An action-focused coping. International Journal of Sport Sciences & Coaching, 4(1), 47–91.

- Hanin, Y. L. (Ed.). (2000). Emotions in sport.Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- McNair, D. M., Lorr, M., & Droppleman, L. F. (1971).Profile of mood state manual. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service.

- Morgan, W. P. (1985). Selected psychological factors limiting performance: A mental health model. In D. H. Clarke & H. M. Eckert (Eds.), Limits of human performance (pp. 70–80). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Morgan, W. P., Brown, D. R., Raglin, J. S., O’Connor, P. J., & Elickson, K. A. (1987). Psychological monitoring of overtraining and staleness. British Journal of Medicine, 21(3), 107–114.

- Morgan, W. P., & Pollock, M. L. (1977). Psychological characterization of the elite distance runner. In P. Milvy (Ed.), Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 301, 382–403.

- Raglin, J. S. (2001). Psychological factors in sport performance. The mental health model revisited. Sports Medicine, 31(12), 875–890.

- Terry, P. (1995). The efficacy of mood state profiling with elite performers: A review and synthesis. The Sport Psychologist, 9, 309–324.

See also: