In many ways, the history of sport psychology mirrors the history of other longstanding disciplines, including psychology, physical education, and other kinesiology-related disciplines, and has been influenced by larger sociocultural trends for decades, for example, the growth of the Olympic movement, professionalization of sport, and women’s liberation. Progressing through a number of eras, sport psychology has grown into a dynamic and continually advancing field. Although there are many detailed written histories of sport psychology, the purpose here is to provide a brief overview. Specifically, this entry begins with a summary of major time periods and key contributors and concludes with general remarks on sport psychology and its development. Importantly, most historical accounts of the field are described from a North American or European white male perspective. However, recent efforts have aimed to recognize and share a more holistic history inclusive of diverse individuals all over the world. Attempts are thus made here to present these global contributions. Finally, the history of sport psychology cannot truly be divorced from the history of exercise psychology. However, to highlight the historical accounts that uniquely shape these disciplines today, the history of exercise psychology is described in a separate entry of this encyclopedia.

Eras in the History of Sport Psychology

The history of sport psychology has often been organized into six key eras or time periods that mark the field’s development. These eras serve as rough guidelines for retrospectively examining events that have shaped sport psychology today. The eras include (1) the prehistory of the field from antiquity to the early 1900s, (2) the development of sport psychology as a specialty in the 1920s and 1930s of the 20th century, (3) preparation for the discipline between the 1940s and 1960s, (4) the establishment of the academic discipline in the late 1960s and 1970s, (5) the science and practice of sport psychology between the late 1970s and 1990s, and (6) contemporary sport psychology over the last decade.

Era 1: Pre-History (Antiquity–Early 1900s)

While most accounts of the history of sport psychology start in the late 1800s, interest in the area can be traced back to ancient times. For example, with the start of the Olympic Games around 776 BCE, the ancient Greeks embraced the mind–body connection and discussed both physical and mental preparation of athletes. In fact, the ancient Greeks are said to be among the first to systematically explore athletic performance with much of the work paralleling modern-day study in the areas of sports medicine and sport psychology. For instance, comparisons have been made between the Greek tetrad system used to prepare athletes for competition (preparation, concentration, moderation, and relaxation) and the contemporary concept of periodization where training occurs in phases.

Fast forwarding to the Victorian era of the late 1800s in the United States and Great Britain, athletes, educators, journalists, and others demonstrated interest in the many topics studied in sport psychology today, such as the psychological characteristics of high-level athletes as well as cultural issues in the sporting world. By 1894, French physician Philippe Tissie and American psychologist Edward Scripture had published some of the first studies in the field. While Tissie studied psychological changes in endurance cyclists, Scripture examined reaction time in fencers and runners. Notably, Scripture’s work reflected efforts to establish a new psychology that focused on data collection and experimentation versus subjective opinion as well as an emphasis on applying scientific findings to the real world (e.g., enhancing athletic performance). Although less recognized, Harvard professor G. W. Fitz was also examining reaction time in athletes around the same time. In 1898, American psychologist Norman Triplett conducted the first known experiment to blend the principles of sport and social psychology. Examining the influence of others on cycling performance, Triplett’s study contributed to the development of social facilitation theory often studied in contemporary sport and exercise settings. Researchers continued to explore these and related topics throughout the early 1900s; American psychologists Karl Lashley and John B. Watson conducted a series of studies on skill acquisition in archery.

Fast forwarding to the Victorian era of the late 1800s in the United States and Great Britain, athletes, educators, journalists, and others demonstrated interest in the many topics studied in sport psychology today, such as the psychological characteristics of high-level athletes as well as cultural issues in the sporting world. By 1894, French physician Philippe Tissie and American psychologist Edward Scripture had published some of the first studies in the field. While Tissie studied psychological changes in endurance cyclists, Scripture examined reaction time in fencers and runners. Notably, Scripture’s work reflected efforts to establish a new psychology that focused on data collection and experimentation versus subjective opinion as well as an emphasis on applying scientific findings to the real world (e.g., enhancing athletic performance). Although less recognized, Harvard professor G. W. Fitz was also examining reaction time in athletes around the same time. In 1898, American psychologist Norman Triplett conducted the first known experiment to blend the principles of sport and social psychology. Examining the influence of others on cycling performance, Triplett’s study contributed to the development of social facilitation theory often studied in contemporary sport and exercise settings. Researchers continued to explore these and related topics throughout the early 1900s; American psychologists Karl Lashley and John B. Watson conducted a series of studies on skill acquisition in archery.

Perhaps the person who demonstrated the most consistent interest in sport psychology during this era was the French founder of the modern Olympic movement, Pierre de Coubertin. A prolific writer, Coubertin wrote numerous articles relevant to topics studied in sport psychology today, such as the reason children participate in athletics, the importance of self-regulation, and the role of psychological factors in performance improvement. He was also the catalyst in organizing several Olympic Congresses, two of which focused on the psychological aspects of sport. Interested in the blend between body, character, and mind, Coubertin’s efforts garnered publicity around the critical role of psychology in sporting activity and continued to influence the field’s development well into the 1940s.

The contributions of this era involved several noteworthy psychologists, physical educators, and physicians whose work demonstrated interest in what is now referred to as the field of sport psychology. However, while the work of these scholars dabbled in the world of sports, none of these individuals were considered sport psychology specialists who made consistent contributions. Few concerted efforts were made to systematically study the area until the 1920s.

Era 2: The Development of Sport Psychology as a Specialty (1920s–1930s)

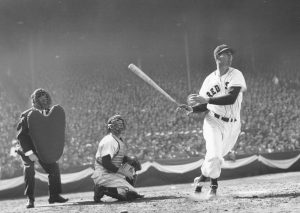

In the 1920s and 30s, professionals continued to show interest in the psychological aspects of sport through periodic writing, research, and exploration. For example, baseball great Babe Ruth was brought to Columbia University in 1921 and psychologically tested to determine the reasons for his exceptional hitting skills. In 1926, American psychologist Walter Miles, his student B. C. Graves, and legendary football coach Pop Warner conducted an interesting study on the influence of signal calling on charging times among the offensive line players.

However, it is also in this era that individuals from around the world began to specialize in the area by developing more systematic lines of research, presentations, and publications that marked a more sustained interest in the psychological aspects of sport. In Charlottenburg, Germany, Robert Werner Schulte started one of the first sport psychology laboratories in 1920 at the Deutsche Hochshule für Leibesübungen where he wrote a book titled Body and Mind in Sport and continued his work until his untimely death in 1933. In Russia, notable scholars Piotr Antonovich Roudik and Avksenty Cezarevich Puni began work at the Physical Institutes of Culture in Moscow and Leningrad, respectively. Roudik conducted studies on perception, memory, attention, and imagination while Puni examined psychological preparation and the effects of competition on athletes.

Around the same time, Coleman Griffith was directing the Research in Athletics Laboratory at the University of Illinois. Griffith, who is recognized as the father of North American sport psychology, published approximately 25 studies on topics ranging from motor learning to personality and character. He also published two classic books, Psychology of Coaching (1926) and Psychology of Athletics (1928), and outlined the key functions of the sport psychologist. Griffith’s laboratory closed during the Great Depression of the 1930s, but in 1938, he was hired by the Chicago Cubs to assist in improving the team’s athletic performance. Unfortunately, Griffith’s applied work is said to have been far from successful because of resistance from players and coaches.

The 1920s and 1930s were characterized by not only scholars who dabbled in sport psychology work, but also those across the globe who set up sport psychology laboratories and devoted significant portions of their career to studying the area. Interestingly, with the exception of some Russian scholars whose work continued through the 1960s, the research findings of these early pioneers had little direct influence on the scientific advancement of the field. Griffith, for example, was ahead of his time but worked in isolation with few students to immediately build upon his work. Still, the emergence of sport psychology as a discipline was ready to begin.

Era 3: Preparation for the Discipline (1940s–1960s)

Scholars who trained future generations of students and professionals set the stage for the development of sport psychology as an academic discipline. As previously mentioned, Puni’s work in Russia continued well into the 1960s and 70s and is still recognized today. The same is true in North America where Franklin Henry of the University of California at Berkeley established a psychology of physical activity program and trained physical educators. Upon earning their graduate degrees, these students initiated systematic lines of research across the country. While much of Henry’s work focused on what would now be considered motor learning and control, some of his students examined social psychology topics such as athlete personality and the arousal–performance relationship. This era of sport psychology research was also likely influenced by sociocultural events, such as increasing emphasis on performance at the Olympic Games, the Cold War, and the space race, which spurred considerable interest in the development of science in many fields.

On the applied front, the work of David Tracy is noteworthy as he consulted with semipro baseball players as well as the St. Louis Browns’ major league team. Tracy helped athletes improve their performance by teaching relaxation skills, using confidence building techniques, autosuggestion, and hypnosis. His work is crucial to this era in that it garnered a great deal of publicity for the practice of sport psychology. It was reported that the Browns’ front office believed that if other industries used psychologists, then it would be logical for professional baseball to do so as well. This may have helped initiate a shift in the attitudes of sportspersons and administrators toward the usefulness of sport psychology practitioners.

In addition to Tracy, the work of female pioneer Dorothy Hazeltine Yates is also noteworthy. Best known for her consulting with university boxers, Yates emphasized the use of positive affirmations and relaxation to enhance performance. She also taught a psychology course for athletes and aviators. Embracing the science–practitioner model, she went on to conduct an assessment of her interventions with boxers. A reflection of her work reveals that Yates made important contributions in an otherwise male-dominated field.

Era 4: Establishment of Academic Sport Psychology (Late 1960s–1970s)

The latter part of the 1960s was marked by a major occasion. The First World Congress of Sport Psychology was held in Rome, Italy, in 1965. While few delegates were considered sport psychologists given that the field was only emerging as a discipline, this event marked the beginning of worldwide interest and institutionalization of the field. It was here that the International Society of Sport Psychology (ISSP) was born. With Ferruccio Antonelli of Italy as its first president, the inaugural issue of the International Journal of Sport Psychology arrived just five years later in 1970. Serving as a model, ISSP inspired the development of several other professional organizations of sport psychology across the globe, including the North American Society for the Psychology of Sport and Physical Activity in 1966, the British Society of Sports Psychology in 1967, the French Society of Sport Psychology in 1967, the Canadian Society for Psychomotor Learning and Sport Psychology in 1969, and the German Association of Sport Psychology in 1969. Born out of disagreements within ISSP, the European Federation of Sport Psychology (FEPSAC) was founded in 1969 with female pioneer Ema Geron of Bulgaria as its first president. Both ISSP and FEPSAC remain prominent influences on the field today.

In the late 1960s and 70s, physical education as an academic discipline was firmly taking hold in the United States. Professors were asked to begin research programs in all the sport sciences, curriculums were revised to include more academic sport science coursework, and graduate programs were developed. Sport psychology, now considered distinct from motor learning and control, was a part of this change. Increased activity on the applied side of the field was also occurring during this era, albeit not without controversy. In 1966, clinical psychologists Tom Tutko and Bruce Ogilvie wrote a controversial book, Problem Athletes and How to Handle Them, and developed the Athletic Motivation Inventory, a personality assessment that was said to predict athletic success. The book was controversial because it suggested that athletes were problematic and needed to be controlled, while some scholars felt that their personality test was based on questionable science. Despite the controversy, Ogilvie was active in working with elite athletes and teams and was seen as a role model for many young professionals with an interest in applied work. In fact, he has been called the father of applied sport psychology in North America.

Era 5: Bridging Science and Practice in Sport Psychology (Late 1970s–1990s)

As the name of the era implies, it was between the late 1970s and 1990s that sport psychology came of age as both a science and an area of professional practice. This era was characterized by increasing interest in the field with scientists devoting their entire careers to the field, and a growing number of practitioners working directly with athletes and coaches. For example, the U.S. Olympic Committee developed a sport psychology advisory board, hired its first resident sport psychologist, and sent its first sport psychologist to the Olympic Games. New academic journals, including the Journal of Sport Psychology (1979; known as the Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology since 1988), The Sport Psychologist (1986), the Journal of Applied Sport Psychology (1989), and the Korean Journal of Sport Psychology (1989), were published. The development of organizations to meet the needs of a growing field continued. For example, the Japanese Society of Sport Psychology was developed in 1973 followed by the Korean Society of Sport Psychology in the 1980s. Following the dissolution of other related organizations, the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences was developed in 1984 with The Sport and Exercise Scientist becoming its official publication. The Association for Applied Sport Psychology (formerly the Association for the Advancement of Applied Sport Psychology) was established in 1986, established its Certified Consultant designation in 1991, and continues to be the largest applied sport psychology organization in the world. In 1986, the American Psychological Association formed a new division, Division 47, devoted specifically to exercise and sport psychology. Born out of the First National Congress of Sport Psychology in Barcelona, the Spanish Federation of Sport Psychology was founded in 1987. Shortly thereafter, the Australian Psychological Association was developed with sport and exercise psychology as a specialization in 1988, followed by the creation of the Asian South Pacific Association of Sport Psychology in 1989.

Finally, women of this era were afforded more opportunities and entered the field in greater numbers thanks to the concerted efforts of several female pioneers, including Ema Geron, Dorothy Yates, Dorothy Harris, Jean Williams, Carole Oglesby, Tara Scanlan, Maureen Weiss, and Diane Gill, to name just a few. Recently, determined efforts have been made to write these female pioneers into the history of the field and recognize their many contributions.

Era 6: Contemporary Sport and Exercise Psychology (2000–Present)

Contemporary sport psychology is a firmly established discipline. The popularity of the field was evidenced by over 700 delegates from 70 countries attending the 2009 World Congress of Sport Psychology held in Morocco. A large number of universities now offer specializations at the graduate level with hundreds of research studies being conducted every year. Reflecting a shift in the field’s focus toward the inclusion of both sport and exercise contexts, the International Journal of Sport Psychology changed its name to the International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology (IJSEP) in 2002. The British Psychological Society also developed a sport and exercise psychology division in 2004. Greater attention is being paid to the practice of sport psychology with the development of an applied journal, The Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, published by the Association for Applied Sport Psychology in 2010. As sport psychology becomes increasingly popular through media outlets and social networking, Olympic and professional athletes continue to work with sport psychology specialists, as do a number of developing and recreational athletes.

With the growth of both the science and practice of sport psychology, a number of major changes are occurring in the field today. For example, fueled by rising obesity rates and a decrease in physical activity in many Western countries, there has been an explosion of interest in health and exercise-related research in the last decade. Exercise motivation and adherence, the role of physical activity in mental health, and the psychology of athletic injuries have all been topics of considerable interest (see also the entry “History of Exercise Psychology”). Life skill development, cultural issues, and diversity in the sport context have also become popular areas of inquiry. In addition to the topics studied, the methods employed are also expanding. An increase in qualitative research methods in particular is evidenced by the development of new journals solely devoted to this type of research like Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise, and Health.

At the same time sport psychology has seen tremendous growth and advancement, several important challenges face the field. For example, although they are more widely accepted, qualitative research methods have been criticized for their subjective nature and have led to some debate over the best way of gaining knowledge. Economic support for higher education in many Western societies has declined and caused sport psychology laboratories to become more conscious of the need to secure external funding (e.g., grants, fellowships) to support their research efforts. Tension between researchers and practitioners of sport psychology continues, which has led various professional organizations to purposefully attempt to bridge the gap. Other concerns include the job outlook for many being trained in the field. While sport psychology has certainly grown, academic positions are somewhat limited, and few practitioners will land full-time positions working with athletes and teams. Finally, perhaps the greatest challenge is defining the educational training necessary to become a practitioner in sport psychology. Disagreement over the role of kinesiology versus counseling-based training has led to heated debates among professionals. Increasing attention paid to certifications, licensures, and ethical standards are intended to safeguard against those who may unethically practice sport psychology without the appropriate competencies. Addressing these challenges and embracing the aforementioned successes of the field will fuel the growth of sport psychology in the future.

Conclusion

While sport psychology emerged out of other disciplines, the field certainly has a longer and deeper history than has often been described. Recent efforts have unveiled the contributions of individuals who demonstrated interest in the psychological aspects of sport long before Coleman Griffith and brought to light a history characterized by diverse and global influences not previously recognized. Sport psychology is a worldwide phenomenon with strong research and practice components that parallels the growth of other established disciplines, including psychology and physical education.

References:

- Green, C. D., & Benjamin, L. T. (2009). Psychology gets in the game: Sport, mind, and behavior, 1880–1960. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Kornspan, A. S. (2012). History of sport and performance psychology. In S. M. Murphy (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of sport and performance psychology (pp. 3–23). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Krane, V., & Whaley, D. E. (2010). Quiet competence: Writing women into the history of U.S. sport and exercise psychology. The Sport Psychologist, 18, 349–372.

- Ryba, T. V., Schinke, R. J., & Tenenbaum, G. (2010). The cultural turn in sport psychology. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Vealey, R. S. (2006). Smocks and jocks outside the box: The paradigmatic evolution of sport and exercise psychology. Quest, 58, 128–159.

- Weinberg, R. S., & Gould, D. (2011). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

See also: