Understanding and enhancing motivation is one of the most popular areas of research in psychology, as well as sport and exercise psychology. In psychology and sport psychology, this research has primarily addressed the role of motivation in individual lives, especially when addressing motivation in achievement contexts. Motivation has usually taken the form of managing the motivation of others, which is often the concern of the parent, the teacher, or the coach, or of managing one’s own motivation.

It has been argued (e.g., Roberts, 2001) that the term motivation is overused and vague. There are at least 32 theories of motivation that have their own definition of the construct (Ford, 1992), and there are almost as many definitions as there are theorists (Pinder, 1984). It is defined so broadly by some as to incorporate the whole field of psychology, and so narrowly by others as to be almost useless as an organizing construct. The solution for most has been to abandon the term and use descriptions of cognitive processes, such as self-regulation and self-systems, processes such as personal goals and goal setting, or emotional processes. However, most contemporary theorists agree on the important assumption that motivation is not an entity, but a process (e.g., Maehr & Braskamp, 1986). To understand motivation, we must make an attempt to understand the process of motivation and the constructs that drive the process.

Understanding Motivation And Achievement Behavior

Motivational processes can be defined by the psychological constructs that energize, direct, and regulate achievement behavior. Motivation theories may be viewed as being on a continuum ranging from deterministic to mechanistic to organismic to cognitive (for a more extensive treatment of motivation theories, see Ford, 1992; Weiner, 1972). Deterministic and mechanistic theories view humans as passive and driven by psychological needs or drives. Organismic theories acknowledge innate needs but also recognize that a dialectic occurs between the organism and the social context. Cognitive theories view humans as active and initiating action through subjective interpretation of the achievement context. Contemporary theories tend to be organismic or social-cognitive and are based on more dynamic and sophisticated conceptions that assume the human is an active participant in decision making and in planning achievement behavior (e.g., Bandura, 1986; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Kuhl, 1986; Maehr & Nicholls, 1980; Nicholls, 1989). Although organismic approaches are experiencing a resurgence in the literature (Hagger & Chatzisarantis, in press), the majority of motivation research in physical activity contexts over the past 30 years has adopted a social-cognitive approach (e.g., Duda, 1992, 2001; Duda & Hall, 2001; Duda & Whitehead, 1998; Roberts, 1984, 1992, 2001; Roberts, Treasure, & Kavussanu, 1997). Specifically, the motivation theory that has emerged as the most popular in sport and physical activity contexts is achievement goal theory. In 1998, Duda and Whitehead identified 135 research studies reported in the 1990s, yet just 2 years later Brunel (2000) identified 160 studies. As we go to press, the number stands at over 200!

Accordingly, in this article we take a generally socialcognitive perspective, where achievement may be defined as the attainment of a personally or socially valued achievement goal that has meaning for the person in a physical activity context (e.g., losing weight, improving a skill, defeating an opponent). Achievement is subjectively defined, and success or failure in obtaining the goal is a subjective state based on the participant’s assessment of the outcome of the achievement behavior (e.g., Maehr & Nicholls, 1980; Spink & Roberts, 1981).

Achievement Goal Theory In Sport And Physical Activity

The history of achievement goal theory (in general and in sport) has been reviewed in several other publications (e.g., Duda, 2005; Duda & Hall, 2001; Roberts, 2001; Roberts et al., 1997), so the present chapter focuses on identifying key constructs, tenets, and limitations of the theory, reviewing empirical support, and presenting recent proposals for expanding or restructuring the approach.

The history of achievement goal theory (in general and in sport) has been reviewed in several other publications (e.g., Duda, 2005; Duda & Hall, 2001; Roberts, 2001; Roberts et al., 1997), so the present chapter focuses on identifying key constructs, tenets, and limitations of the theory, reviewing empirical support, and presenting recent proposals for expanding or restructuring the approach.

Achievement goal theory assumes that the individual is an intentional, goal-directed organism who operates in a rational manner, and that achievement goals govern achievement beliefs and guide subsequent decision making and behavior in achievement contexts. It is argued that to understand the motivation of individuals, the function and meaning of the achievement behavior to the individual must be taken into account and the goal of action understood. Individuals give meaning to their achievement behavior through the goals they adopt. It is these goals that reflect the purposes of achievement striving. Once adopted, the achievement goal determines the integrated pattern of beliefs that undergird approach and avoidance strategies, the differing engagement levels, and the differing responses to achievement outcomes. By so recognizing the importance of the meaning of behavior, it becomes clear that there may be multiple goals of action, not one (Maehr & Braskamp, 1986). Thus, variation of achievement behavior may not be the manifestation of high or low motivation per se, or the satisfaction of needs, but the expression of different perceptions of appropriate goals with their attendant constellation of cognitions. An individual’s investment of personal resources, such as effort, talent, and time, in an activity is dependent on the achievement goal of the individual.

The overall goal of action in achievement goal theory, thereby becoming the conceptual energizing force, is assumed to be the desire to develop and demonstrate competence and to avoid demonstrating incompetence. The demonstration and development of competence is the energizing construct of the motivational processes of achievement goal theory. But competence has more than one meaning. One of Nicholls’s (1984) conceptual contributions was to argue that more than one conception of ability exists, and that achievement goals and behavior may differ depending on the conception of ability held by the person. Nicholls argued that two conceptions of ability (at least) are manifest in achievement contexts, namely, an undifferentiated concept of ability, where ability and effort are not differentiated by the individual, either because he or she is not capable of differentiating, as is the case with young children, or because the individual chooses not to differentiate; and a differentiated concept of ability, where ability and effort are differentiated (Nicholls, 1984, 1989).

Nicholls (1976, 1978, 1980) argued that children originally possess an undifferentiated conception of ability in which they are not able to differentiate the concepts of luck, task difficulty, and effort from ability. From this undifferentiated perspective, children associate ability with learning through effort, so that the more effort one puts forth, the more learning (and ability) one achieves. Following a series of experiments, Nicholls (1978; Nicholls & Miller, 1983, 1984a, 1984b) determined that by the age of 12 children are able to differentiate luck, task difficulty, and effort from ability, enabling a differentiated perspective. When utilizing this differentiated perspective, children begin to see ability as capacity and that the demonstration of competence involves outperforming others. In terms of effort, high ability is inferred when outperforming others while expending equal or less effort or performing equal to others while expending less effort.

Individuals will approach a task or activity with certain goals of action reflecting their personal perceptions and beliefs about the particular achievement activity in which they are engaged and the form of ability they wish to demonstrate (Dennett, 1978; Nicholls, 1984, 1989). The conception of ability they employ and the ways they interpret their performance can be understood in terms of these perceptions and beliefs. These perceptions and beliefs form a personal theory of achievement at the activity (Nicholls, 1989; Roberts, 2001; Roberts et al., 1997), which reflects the individual’s perception of how things work in achievement situations. The adopted personal theory of achievement affects one’s beliefs about how to achieve success and avoid failure at the activity. Therefore, people will differ in which of the conceptions of ability and criteria of success and failure they use, and in how they use them, based on their personal theory of achievement.

The two conceptions of ability thereby become the source of the criteria by which individuals assess success and failure. The goals of action are to meet the criteria by which success and failure are assessed. Nicholls (1989) identifies achievement behavior utilizing the undifferentiated conception of ability as task involvement and achievement behavior utilizing the differentiated conception of ability as ego involvement. When the individual is task involved, the goal of action is to develop mastery, improvement, or learning, and the demonstration of ability is self-referenced. Success is realized when mastery or improvement has been attained. The goal of action for an ego-involved individual, on the other hand, is to demonstrate ability relative to others or to outperform others, making ability other-referenced. Success is realized when the performance of others is exceeded, especially when expending less effort than others (Nicholls, 1984, 1989).

In this article, when we refer to the motivated state of involvement of the individual, we use the terms ego involvement and task involvement to be consistent with Nicholls’s use of the terms. In addition, when we refer to individual differences (e.g., self-schemas, personal theories of achievement, dispositions), we use the terms task orientation and ego orientation. Other motivation theorists (e.g., Dweck, 1986; Dweck & Legget, 1988; Elliot, 1997; Maehr & Braskamp, 1986) have used different terms to describe the same phenomena. When we refer to the situational determinants of motivation, the achievement cues inherent in the context, and the schemas emerging from achievement situations, we are consistent with Ames (1984a, 1992a, 1992b, 1992c) and refer to the task-involving aspect of the context as mastery criteria and the ego-involving aspect of the context as performance criteria. Finally, when we refer to the competence goals defined by Elliot (e.g., 1997) and colleagues, we use the terms mastery and performance goals.

Whether one is engaged in a state of ego or task involvement is dependent on one’s dispositional orientation, as well as the perception of achievement cues in the context (Nicholls, 1989). Let us consider first two levels of individual differences: the state of goal involvement and the goal orientation.

States of Goal Involvement

Each of the theories of achievement goal motivation proffered by the major theorists (e.g., Ames, 1984a, 1984b, 1992a, 1992b, 1992c; Dweck, 1986; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Elliot, 1997; Maehr & Braskamp, 1986; Maehr & Nicholls, 1980; Nicholls, 1984, 1989) hold that important relationships exist between the states of goal involvement and achievement striving. According to Nicholls, if the person is task-involved, the conception of ability is undifferentiated and perceived ability becomes less relevant, as the individual is trying to demonstrate or develop mastery at the task rather than demonstrate normative ability. As the individual is trying to demonstrate mastery or improvement, the achievement behaviors will be adaptive in that the individual is more likely to persist in the face of failure, to exert effort, to select challenging tasks, and to be interested in the task (Dweck, 1986; Nicholls, 1984, 1989; Roberts, 1984, 1992; Roberts et al., 1997). On the other hand, if the individual is ego-involved, the conception of ability is differentiated and perceived ability is relevant, as the individual is trying to demonstrate normative ability, or avoid demonstrating inability, and how his or her ability fares with comparative others becomes important.

If the individual is ego-involved and perceives himself or herself as high in ability, that person is likely to approach the task and engage in adaptive achievement behaviors. These are the people who seek competitive contests and want to demonstrate superiority. When perceived ability is high, demonstrating high normative ability is likely; therefore the individual is motivated to persist and demonstrate that competence to pertinent others. If one can demonstrate ability with little effort, however, this is evidence of even higher ability. Thus, the ego-involved person is inclined to use the least amount of effort to realize the goal of action (Nicholls, 1984, 1992; Roberts, 1984; Roberts et al., 1997).

On the other hand, if the perception of ability is low, the individual will realize that ability is not likely to be demonstrated, and he or she is likely to manifest maladaptive achievement behaviors (Nicholls, 1989). Maladaptive behaviors are avoiding the task, avoiding challenge, reducing persistence in the face of difficulty, exerting little effort, and, in sport, dropping out if achievement of desired goals appears difficult. These are the people who avoid competitive contests, as their lack of high normative ability is likely to be exposed. Although the participant may view these avoidance behaviors as adaptive because they disguise a lack of ability, they are considered maladaptive in terms of achievement behavior.

It has been argued (e.g., Duda & Hall, 2001; Roberts, 2001; Treasure et al., 2001) that the states of involvement are mutually exclusive (i.e., one is either ego or task involved), even though this notion has been questioned in light of parallel processing models of information processing (Harwood & Hardy, 2001). Goal states are very dynamic and can change from moment to moment as information is processed (Gernigon, d’Arripe-Longueville, Delignières, & Ninot, 2004). An athlete may begin a task with strong task-involved motivation, but contextual events may make the athlete wish to demonstrate superiority to others, and so the athlete becomes ego-involved in the task. Thus, goal states are dynamic and ebb and flow depending on the perception of the athlete.

The measurement of goal states is a particularly challenging task. It has been done in three ways. One has been to take an existing goal orientation measure and reword the stem to obtain a state measure (e.g., Hall & Kerr, 1997; Williams, 1998). A second has been to use single-item measures asking participants to indicate whether they focus on achieving a personal standard of performance (self-referenced) or beating others in an upcoming contest (other-referenced; e.g., Harwood & Swain, 1998). The third way is to ask participants to view video replays of the event and retrospectively reflect on their goal involvement at any one point in the contest (e.g., J. Smith & Harwood, 2001). Although the first two procedures may be more predictive of the initial state of involvement than the orientation measures per se (Duda, 2001), Duda has argued that these procedures may not capture the essence of task and ego involvement. In addition, it may be argued that because the states are so dynamic, even if you are able to reflect the state of involvement at the outset of the competition, as the state of involvement ebbs and flows as task and competitive information is processed, we have no indication of the changes that may occur (Roberts, 2001). It is naive and conceptually inconsistent to assume that the state of involvement will remain stable throughout the contest.

The best way of estimating the state of involvement currently available is the procedure used by J. Smith and Harwood (2001). At least we obtain participants’ observations of their goal involvement at different times of the contest. This is a superior procedure to determine goal involvement that takes into consideration its dynamic nature. However, this procedure is very labor-intensive; it has to be done with each participant over the course of the contest.

Clearly, the development of an assessment procedure for the state of goal involvement is a major task, especially when one recognizes that achievement goal theory is predicated on one’s task or ego involvement in the achievement task. As has been the case with measuring state anxiety, obtaining repeated measures while an athlete is engaged in competition is a practical nightmare. And we have to recognize that repetitive assessments of goal involvement during a competitive encounter may have the effect of changing an athlete’s goal involvement state (Duda, 2001)! Certainly, forcing task-involved athletes to consider why they are doing what they are doing may make them more self-aware and ego-involved in the task. To reduce the likelihood of this happening, the retrospective recall strategy of J. Smith and Harwood (2001) is clearly the better procedure, despite its disadvantages.

Goal Orientations

It is assumed that individuals are predisposed (e.g., by their personal theory of achievement) to act in an egoor taskinvolved manner; these predispositions are called achievement goal orientations. Individual differences in the disposition to be egoor task-involved may be the result of socialization through taskor ego-involving contexts in the home or experiences in significant achievement contexts (e.g., classrooms, physical activities; Nicholls, 1989; Roberts et al., 1997).

Goal orientations are not to be viewed as traits or based on needs. Rather, they are cognitive schemas that are dynamic and subject to change as information pertaining to one’s performance on the task is processed. But the orientations do have some stability over time (Duda & Whitehead, 1998; Roberts, Treasure, & Balague, 1998). These self-cognitions are assumed to be relatively enduring. As examples, Dweck (1986) considers that one’s theory of intelligence is relatively stable, and Nicholls (1984) considers one’s conceptualization of ability to be stable as well. Thus, being taskor ego-oriented refers to the inclination of the individual to be taskor ego-involved.

To measure goal orientations, researchers have typically created questionnaires that are assumed to assess ego and task goal orientations (e.g., Nicholls, Patashnik, & Nolen, 1985). Although Dweck and her colleagues (e.g., Dweck & Leggett, 1988) conceptualize and measure achievement goals as dichotomous, it has been more usual for researchers to assume that the two goals are conceptually orthogonal and to measure them accordingly (Duda & Whitehead, 1998; Nicholls et al., 1985; Roberts et al., 1998).

Nicholls (1989) has argued that to assess personal achievement goals, individuals should be asked about the criteria that make them feel successful in a given situation, rather than noting their definition of competence. In line with this suggestion, Roberts and colleagues (Roberts & Balague, 1989; Roberts et al., 1998; Treasure & Roberts, 1994b) have developed the Perception of Success Questionnaire (POSQ), and Duda and colleagues (Duda & Nicholls, 1992; Duda & Whitehead, 1998) have developed the Task and Ego Orientation in Sport Questionnaire (TEOSQ). Both have demonstrated acceptable reliability and construct validity (Duda & Whitehead, 1998; Marsh, 1994; Roberts et al., 1998). Although other scales exist, the POSQ and the TEOSQ best meet the conceptual criteria of measuring orthogonal achievement goals in sport (Duda & Whitehead, 1998). When developing scales in the future, the constructs identified must be conceptually coherent with achievement goal theory. This has not always been the case in the past (e.g., Gill & Deeter, 1988; Vealey & Campbell, 1988), and this has created some conceptual confusion (Marsh, 1994).

Motivational Implications of Goal Orientations

The majority of research in goal orientations has focused on the antecedents and consequences of goal orientations. In this section, we briefly review the research on the association between achievement goals and both cognitive and affective variables, and important outcome variables.

Perceptions of Competence

One of the fundamental differences between task and ego-oriented athletes is the way they define and assess competence. Task-oriented individuals tend to construe competence based on self-referenced criteria and are primarily concerned with mastery of the task, so they are more likely than ego-oriented individuals to develop perceived competence over time (Elliott & Dweck, 1988). In contrast, ego oriented individuals feel competent when they compare favorably in relation to others, so high perceived relative ability or competence is less likely to be maintained in ego orientation, especially for those participants who already question their ability (see Dweck, 1986). This prediction of achievement goal theory has been supported in numerous studies with a variety of conceptualizations of competence perceptions (Chi, 1994; Cury, Biddle, Sarrazin, & Famose, 1997; Kavussanu & Roberts, 1996; Nicholls & Miller, 1983, 1984a; Vlachopoulos & Biddle, 1996, 1997).

Thus, several lines of research suggest that using the task-involving conception of achievement to judge demonstrated competence enhances resiliency of perceived competence. The implications of these findings are particularly important in learning contexts. For example, for individuals who are beginning to learn a new physical skill, holding a task orientation may be instrumental in facilitating perceptions of competence, effort, and persistence, and consequently success in the activity. It is not surprising that Van Yperen and Duda (1999), in their study with Dutch male soccer players, found that athletes high in task orientation were judged by their coaches to possess greater soccer skills from pre to postseason. A task orientation fosters perceptions of competence and success for individuals who are either high or low in perceived competence and encourages the exertion of effort. An ego orientation, on the other hand, may lower perceptions of success, perceived competence, and thus effort, especially for those individuals who already are unsure of their ability.

Beliefs about the Causes of Success

Nicholls (1989, 1992) suggests that one’s goal in conjunction with one’s beliefs about the causes of success in a situation constitute one’s personal theory of how things work in achievement situations. For individuals with low perceived ability, a belief that ability causes success will most likely result in frustration, a lack of confidence and may even lead to dropping out, as these individuals feel they do not possess the ability required to be successful. In the physical activity domain, where practice and hard work are so essential for improvement, especially at the early stages of learning, the belief that effort leads to success is the most adaptive belief for sustaining persistence.

Research on young athletes (e.g., Hom, Duda, & Miller, 1993; Newton & Duda, 1993), high school students (Duda& Nicholls, 1992; Lochbaum & Roberts, 1993), British youth (Duda, Fox, Biddle, & Armstrong, 1992; Treasure & Roberts, 1994a), young disabled athletes participating in wheelchair basketball (White & Duda, 1993), and elite adult athletes (Duda & White, 1992; Guivernau & Duda, 1995; Roberts & Ommundsen, 1996) has consistently demonstrated that a task goal orientation is associated with the belief that hard work and cooperation lead to success in sport. In general, ego orientation has been associated with the view that success is achieved through having high ability and using deception strategies such as cheating and trying to impress the coach. A similar pattern of results has emerged in the physical education context (Walling & Duda, 1995), as well as in research with college students participating in a variety of physical activity classes (e.g., Kavussanu & Roberts, 1996; Roberts, Treasure, & Kavussanu, 1996).

Purposes of Sport

In classroom-based research, ego orientation has been associated with the belief that the purpose of education is to provide one with wealth and social status, which is evidence of superior ability. Task orientation, on the other hand, has been linked to the view that an important purpose of school education is to enhance learning and understanding of the world and to foster commitment to society (Nicholls et al.,1985; Thorkildsen, 1988). Similar findings have been reported in the athletic arena (e.g., Duda, 1989; Duda & Nicholls, 1992; Roberts, Hall, Jackson, Kimiecik, & Tonymon, 1995; Roberts & Ommundsen, 1996; Roberts et al., 1996, 1997; Treasure & Roberts, 1994a; White, Duda, & Keller, 1998), indicating that worldviews cut across educational and sport contexts.

Task orientation has been associated with the belief that the purpose of sport is to enhance self-esteem, advance good citizenship, foster mastery and cooperation (Duda, 1989), encourage a physically active lifestyle (White et al., 1998), and foster lifetime skills and pro-social values such as social responsibility, cooperation, and willingness to follow rules (Roberts & Ommundsen, 1996; Roberts et al., 1996). Likewise, task orientation is associated with the view that the purpose of physical education is to provide students with opportunities for improvement, hard work, and collaboration with peers (Papaioannou & McDonald, 1993; Walling & Duda, 1995). In contrast, ego orientation has been linked to the view that sport should provide one with social status (Roberts & Ommundsen, 1996; Roberts et al., 1996), enhance one’s popularity (Duda, 1989; Roberts & Ommundsen, 1996) and career mobility, build a competitive spirit (Duda, 1989), and teach superiority and deceptive tactics (Duda, 1989; Duda & White, 1992). Ego orientation is also associated with the view that the purpose of physical education is to provide students with an easy class and teach them to be more competitive (Papaioannou & McDonald, 1993; Walling & Duda, 1995).

Affect and Intrinsic Interest

One of the most consistent findings in achievement goal research has been the link between task orientation and experienced enjoyment, satisfaction, and interest during participation in physical activity for high school students (Duda, Chi, Newton, Walling, & Catley, 1995; Duda & Nicholls, 1992), athletes competing in international competition (Walling, Duda, & Chi, 1993), and college students enrolled in a variety of physical activity classes (e.g., Duda et al., 1995; Kavussanu & Roberts, 1996). A positive relationship has also been reported between task orientation and flow, an intrinsically enjoyable experience in college athletes (Jackson & Roberts, 1992). In the studies just cited, ego orientation was either inversely related or unrelated to intrinsic interest, satisfaction, or enjoyment.

Participants with a high task orientation, in combination with either a high or low ego orientation, experience greater enjoyment than those participants who are high in ego orientation and low in task orientation (Biddle, Akande, Vlachopoulos, & Fox, 1996; Cury et al., 1996; Goudas, Biddle, & Fox, 1994; Vlachopoulos & Biddle, 1996, 1997). A task orientation seems to be especially important for continued participation in physical activity as it is associated with enjoyment, and this occurs regardless of one’s perceived success (Goudas et al., 1994) or perceived ability (Vlachopoulos & Biddle, 1997) and intrinsic interest (Goudas, Biddle, Fox, & Underwood, 1995).

Another interesting finding of previous research is the different sources of satisfaction associated with goals. Egooriented athletes glean satisfaction when they demonstrate success in the normative sense and please their coach and friends, whereas task-oriented individuals feel satisfied when they have mastery experiences and perceive a sense of accomplishment during their sport participation (Roberts & Ommundsen, 1996; Treasure & Roberts, 1994a).

Probably the most significant study to illustrate the association of goals with affect was conducted by Ntoumanis and Biddle (1999). They conducted a meta-analysis with 41 independent samples and found that task orientation and positive affect were positively and moderately to highly correlated. The relationship between ego orientation and both positive and negative affect was small. In essence, being task-involved fosters positive affect in physical activities.

Anxiety

Roberts (1986) was the first to suggest that athletes adopting an ego orientation may experience anxiety as a function of whether or not they believe they can demonstrate sufficient competence in an achievement context. Anxiety should be less likely with a task orientation, because an individual’s self-worth is not threatened. Research has generally supported the tenets of goal theory (Roberts, 2001). Task orientation has been negatively associated with precompetitive anxiety (Vealey & Campbell, 1988), cognitive anxiety with young athletes (Ommundsen & Pedersen, 1999), somatic and cognitive anxiety (Hall & Kerr, 1997), task-irrelevant worries and the tendency to think about withdrawing from an activity (Newton & Duda, 1992), and concerns about mistakes and parental criticisms (Hall & Kerr, 1997; Hall, Kerr, & Matthews, 1998). Further, a task orientation has been associated with keeping one’s concentration and feeling good about the game (Newton & Duda, 1992) and with effective use of coping strategies in elite competition (Pensgaard & Roberts, 2003). An ego orientation, on the other hand, has been positively related to state and trait anxiety (Boyd, 1990; Newton & Duda, 1992; Vealey & Campbell, 1988; White & Zellner, 1996), cognitive anxiety in the form of worry (White & Zellner, 1996), getting upset in competition, and concentration disruption during competition (Newton & Duda, 1992; White & Zellner, 1996).

Most studies have been conducted with very young athletes (Hall & Kerr, 1997) or with recreational or physical education students (Hall et al., 1998; Ommundsen & Pedersen, 1999; Papaioannou & Kouli, 1999). Ommundsen and Pedersen remind us, however, that it is not sufficient simply to state that being task-involved is beneficial in terms of anxiety. They found that being task-involved did decrease cognitive trait anxiety, but low perceived competence increased both somatic and cognitive anxiety. This suggests that being task-involved is beneficial, but that perceived competence is an important predictor of anxiety, too. Being task-oriented and perceiving one’s competence to be high are both important antecedents to reduce anxiety in sport.

The most interesting aspect of the recent work with achievement goal theory has been the attention paid to achievement strategies and outcome variables, especially performance, exerted effort, overtraining and dropping out, and cheating in sport. Achievement goal theory and research in educational and sport settings suggest that personal theories of achievement comprise different beliefs about what leads to success (Nicholls, 1989).

Achievement Strategies

Lochbaum and Roberts (1993) were the first to report that emphasis on problem-solving and adaptive learning strategies was tied to a task orientation in a sport setting. Research (Lochbaum & Roberts, 1993; Ommundsen & Roberts, 1999; Roberts et al., 1995; Roberts & Ommundsen, 1996) has demonstrated that task orientation is associated with adaptive achievement strategies, such as being committed to practice, being less likely to avoid practice, learning, and effort. Typically, in these investigations, ego orientation corresponds to a tendency to avoid practice and to a focus on winning during competition. Goals also differentiate athletes in terms of the perceived benefits of practice. Thus, ego-oriented athletes consider practice as a means to demonstrate competence relative to other athletes, whereas their task-oriented counterparts view practice as a means to foster team cohesion and skill development (Lochbaum & Roberts, 1993; Roberts & Ommundsen, 1996).

When choosing post-climbing task feedback strategies, high ego-oriented climbers who were low in perceived ability were more likely to reject task-related and objective performance feedback than were task-oriented climbers (Cury, Sarrazin, & Famose, 1997). In addition, Cury and Sarrazin (1998) found that high-ego and high-ability athletes selected normative feedback and rejected task-relevant information. High-ego-oriented athletes with low ability requested no feedback and discarded objective information. Research has also given evidence that an ego orientation is related to other unacceptable achievement strategies, such as the use of aggression (Rascle, Coulomb, & Pfister, 1998).

These studies demonstrate that the achievement strategies endorsed by physical activity participants are meaningfully related to their goal perspective. Across studies, task orientation was coupled with adaptive learning strategies, the value of practice to learn new skills and improve, and seeking task-relevant information. In contrast, ego-oriented athletes endorsed avoiding practice as an achievement strategy and avoided task-relevant information, preferring normative feedback (but only when high in perceived ability).

Exerted Effort and Performance

There is little research to date investigating exerted effort and performance. One of the first studies to provide evidence of a performance boost from being task-involved was Vealey and Campbell’s (1989). Van Yperen and Duda (1999) found that when football players were task-oriented, an increase in skilled performance (as perceived by the coach) resulted. In addition, the task-oriented players believed that soccer success depended on hard work. Similarly, Theeboom, De Knop, and Weiss (1995) investigated the effect of a mastery program on the development of motor skills of children and found that the task-involved group reported higher levels of enjoyment and reliably exhibited better motor skills than those who were ego-involved.

However, the best evidence thus far that task-oriented athletes perform better than ego-oriented athletes has been presented by Sarrazin, Roberts, Cury, Biddle, and Famose (2002), who investigated exerted effort and performance of adolescents involved in a climbing task. The results demonstrated that task-involved boys exerted more effort than ego-involved boys and performed better (a success rate of 60% versus 42%), and the degree of exerted effort was determined by an interaction of achievement goal, perceived ability, and task difficulty. Ego-involved boys with high perceived ability and task-involved boys with low perceived ability exerted the most effort on the moderate and difficult courses; ego-involved boys with low perceived ability exerted the least effort on the moderate and very difficult courses. Finally, task-involved boys with high perceived ability exerted more effort when the task was perceived as more difficult.

In general, the research has shown that (a) taskinvolved people exhibit (or report) greater effort than others (Cury et al., 1996; Duda, 1988; Duda & Nicholls, 1992; Durand, Cury, Sarrazin, & Famose, 1996; Goudas et al., 1994; Sarrazin et al., 2002; Solmon, 1996; Tammen, Treasure, & Power, 1992), and (b) ego-involved people with low perceived ability exhibit reduced exerted effort as opposed to people with high perceived ability (Cury, Biddle, et al., 1997). And there is developing evidence that being task-involved leads to better performance. To enhance effort, one should focus on being as task-involved as possible: Task-involved people try harder! And task involved people perform better!

Moral Functioning and Cheating

Achievement goals have also been linked to moral cognitions and moral behavior in sport. A number of recent studies have identified fairly consistent relationships between task and ego orientations and sportspersonship, moral functioning, moral atmosphere, and endorsement of aggressive tactics among both youth and adult competitive athletes. In general, studies have shown that being high in ego orientation leads to lower sportspersonship, more self-reported cheating, lower moral functioning (i.e., moral judgment, intention, and self-reported cheating behavior), and endorsement of aggression when compared to high task-oriented athletes (Kavussanu & Ntoumanis, 2003; Kavussanu & Roberts, 2001; Lemyre, Roberts, & Ommundsen, 2002; Lemyre, Roberts, Ommundsen, & Miller, 2001; Ryska, 2003).

In recent research, Lemyre and colleagues (2001, 2002) and Ryska (2003) have found that low ego/high task-oriented young male soccer players consistently endorsed values of respect and concern for social conventions, rules and officials, and opponents. Similar to sportspersonship, moral functioning and aggression, as well as gender differences among these variables, have been highlighted in recent sport psychology research. Kavussanu (Kavussanu & Roberts, 2001; Kavussanu, Roberts, & Ntoumanis, 2002) has consistently found ego orientation to positively predict lower moral functioning and males to be generally higher in ego orientation, lower in task orientation, and significantly lower in moral functioning as well as endorsing more aggression than female players.

Recent research has indicated that the coach-created motivational climate may also serve as a precursor to cheating among competitive youth sport participants. Findings by Miller and colleagues (Miller & Roberts, 2003; Miller, Roberts, & Ommundsen, 2004, 2005) show that a high egoinvolving motivational climate was associated with low sportspersonship, low moral functioning and reasoning, low moral atmosphere, and endorsement of aggression. Boys cheated more than girls, but within gender, ego-involved boys and girls cheated more than task-involved boys and girls. For boys in particular, being ego-involved meant that they were more likely to engage in cheating behavior, to engage in injurious acts, to be low in moral reasoning, and to perceive the moral atmosphere in the team to be supportive of cheating.

Competitive sport often places individuals in conflicting situations that emphasize winning over sportspersonship and fair play. It would be wrong, however, to attribute this to the competitive nature of sport. The results just cited suggest that it is not the competitive context in itself that is the issue. Rather, it may be the salience of ego involvement in the athletic environment that induces differential concern for moral behavior and cheating, rules, respect for officials, and fair play conventions among young players. If athletes are to develop good sportspersonship behaviors and sound moral reasoning, coaches should reinforce the importance of task-involving achievement criteria in the competitive environment.

Burnout

Another outcome variable that is becoming popular in sport research is burnout (see Eklund & Cresswell, Chapter 28). Why is it that some athletes burn out, and what are the precursors of burning out? Some recent research from a motivational perspective has given us some interesting findings. Freudenberger (1980) has explained burnout as a syndrome that includes both physical and emotional exhaustion. These symptoms occur concurrently with patterns of behavior that are strongly achievement oriented (Hall & Kerr, 1997). Individuals experiencing burnout tend to show a strong commitment to the pursuit of goals and set high standards for themselves. Despite personal investment and great persistence, they often experience depression, depersonalization, disillusionment, and dissatisfaction as their goals are continually unmet. Hall et al. (1998) reported a strong relationship among elite athletes’ perfectionism, achievement goals, and aptitudes to perform. It is when athletes continually perceived their ability and their effort levels to be inadequate to meet their achievement goals that the maladaptive nature of their motivational orientation became apparent. The athlete may drop out to maintain any real sense of self-worth.

Cohn (1990) has found that athletes at risk of burning out were likely to either participate in too much training and competition, lacked enjoyment while practicing their sport, or experienced too much selfor other-induced pressure. Investigating young elite tennis players, Gould and colleagues (Gould, 1996; Gould, Tuffey, Udry, & Loehr, 1996; Gould, Udry, Tuffey, & Loehr, 1996) found that burned-out athletes believed they had less input into their own training, were higher in amotivation, and were more withdrawn. The burned-out players did not differ from their non-burned-out counterparts in terms of the number of hours they trained; consequently Gould and colleagues posited that the crucial factors leading to burnout were psychological (motivational) rather than physical in nature. This was confirmed by Lemyre, Treasure, and Roberts (2006), who found that variation in motivation contributed to the onset of burnout.

In a series of studies investigating the psychological determinants of burnout, Lemyre and colleagues examined the relationship between motivational disposition variables at the start of the season and signs of burnout at season’s end. Lemyre (2005) found that elite winter sport athletes who were ego-involved, focused on normative comparisons, and preoccupied with achieving unrealistic goals, who doubted their own ability, and who had a coach and parents who emphasized performance outcomes were more at risk of developing symptoms of burnout than the more task-involved athletes. Lemyre, Roberts, Treasure, Stray Gundersen, and Matt (2004) investigated the relationship between psychological variables and hormonal variation to burnout in elite athletes. Results indicated that variation in basal cortisol accounted for 15% of the variance in athlete burnout, and the psychological variables of perfectionism (20%), perceived task involvement (12%), and subjective performance satisfaction (18%) explained 50% of the total variance (67%) in athlete burnout at the end of the season. These findings are meaningful as they underline the importance of personal dispositions (perfectionism and achievement goals) on burnout vulnerability in elite athletes.

The literature just reviewed addressed achievement goals from an individual difference perspective in the traditional achievement goal framework. It supports meaningful relationships between personal goals of achievement and cognitive and affective beliefs about involvement in physical activity. In addition, we have shown that outcomes such as exerted effort, performance, moral behavior and cheating, and burnout are affected by whether one is task or egoinvolved. But whether one is in a state of task or ego involvement is not only dependent on one’s personal goal of achievement. The context also has an important influence on one’s state of involvement. We address that literature next.

The Motivational Climate

A fundamental tenet of achievement goal theory is the central role the situation plays in the motivation process (Nicholls, 1984, 1989). Consistent with other motivation research that has emphasized the situational determinants of behavior (e.g., deCharms, 1976, 1984; Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2002), research from an achievement goal perspective has examined how the structure of the environment can make it more or less likely that achievement behaviors, thoughts, and feelings associated with a particular achievement goal are adopted. The premise of this line of research is that the nature of an individual’s experience influences the degree to which task and ego criteria are perceived as salient in the context. This is then assumed to affect the achievement behaviors, cognition, and affective responses through individuals’ perception of the behaviors necessary to achieve success (Roberts et al., 1997).

Adopting the term motivational climate (Ames, 1992b) to describe the goal structure emphasized in the achievement context, researchers have examined two dimensions of the motivational climate, mastery and performance, in sport and physical activity. Mastery (or task-involving) climates refer to structures that support effort, cooperation, and an emphasis on learning and task mastery. Conversely, performance (or ego-involving) climates refer to situations that foster normative comparisons, intrateam competition, and a punitive approach by teachers and coaches to mistakes committed by participants.

A study conducted by Parish and Treasure (2003) is representative of much of the extant literature in the area. In this case, the influence of perceptions of the motivational climate and perceived ability on situational motivation and the physical activity behavior of a large sample of adolescent male and female physical education students was examined. Consistent with achievement goal theory, the results showed that perceptions of a mastery climate were strongly related to more self-determined forms of situational motivation (intrinsic and identified motivation) and, along with gender and perceived ability, most significantly predictive of the actual physical activity behavior of the participants. In contrast, perceptions of a performance climate were found to be strongly related to less selfdetermined forms of situational motivation (extrinsic and amotivational) and unrelated to physical activity.

Consistent with the findings reported by Parish and Treasure (2003), the extant literature in physical education and sport suggests that the creation of a mastery motivational climate is likely to be important in optimizing positive (i.e., well-being, sportspersonship, persistence, task perseverance, adaptive achievement strategies) and attenuating negative (i.e., overtraining, self-handicapping) responses (e.g., Kuczka & Treasure, 2005; Miller et al., 2004; Ommundsen & Roberts, 1999; Sarrazin et al., 2002; Standage, Duda, & Ntoumanis, 2003; Standage, Treasure, Hooper, & Kuczka, in press; Treasure & Roberts, 2001). This pattern of findings has been confirmed in a metaanalysis consisting of statistically estimated effect sizes from 14 studies (N = 4,484) that examined the impact of different motivation climates in sport and physical education on cognitive and affective responses (Ntoumanis & Biddle, 1999). The evidence, therefore, supports the position that perceptions of a mastery motivational climate are associated with more adaptive motivational and affective response patterns than perceptions of a performance climate in the context of sport and physical education.

An Interactionist Approach

Achievement goal research has shown that individual variables and situational variables separately influence achievement behavior, cognition, and affect. Although these two lines of research have been conducted in relative isolation, an interactionist approach that looks to combine both types of variable is expected to provide a far more complete understanding of the motivation process. To this end, Dweck and Leggett (1988) suggested that dispositional goal orientations should be seen as an individual variable that will determine the probability of adopting a certain goal or action, that is, task or ego state of goal involvement, and a particular behavior pattern in achievement contexts. Situational variables, such as perceptions of the motivational climate, were proposed as potential moderators of the influence of the individual variables. As Roberts and colleagues (1997) argue, when the situational criteria are vague or weak, an individual dispositional goal orientation should hold sway. In contexts where the situational criteria are particularly salient, it is possible that perceptions of the climate may override an individual’s dispositional goal orientation and be a stronger predictor of behavioral, cognitive, and affective outcomes. It is also proposed that children and young adolescents, who have yet to firm up their personal theories of achievement, may be more susceptible to the influence of situational variables than older adolescents and adults (Roberts & Treasure, 1992).

The result of the limited research that has examined both individual and situational variables has shown that taking into account both of these variables enhances our understanding of the sport context (e.g., Kavussanu & Roberts, 1996; Seifriz, Duda, & Chi, 1992). The limited evidence to date also provides support for Dweck and Leggett’s (1988) contention that situational variables may moderate the influence of goal orientations (e.g., Swain & Harwood, 1996; Treasure & Roberts, 1998). When significant interaction effects emerged, they did so in a manner consistent with a moderation model. Although it is often difficult to statistically find significant interaction effects (Aguinis & Stone-Romero, 1997), the findings of the limited studies that have been conducted are consistent with the fundamental tenets of achievement goal theory and speak to the veracity of investigating the interaction in addition to the main effect of individual and situational variables.

Enhancing Motivation

Research from an achievement goal perspective in sport and physical education has demonstrated that goal orientations and perceptions of the motivational climate are relevant to the ongoing stream of achievement behavior, cognition, and affect. Given the body of empirical work that has documented the adaptive motivation and wellbeing responses of students who perceive mastery or taskinvolving climates, physical education teacher and sport coach education programs would benefit from integrating educational information pertaining to the creation of mastery climates into their curricula. Specifically, researchers interested in the sport and physical education experience need to develop strategies and guidelines and explore ways in which coaches, parents, and other significant social agents can engage in the creation of a mastery or taskinvolving motivational climate.

A paucity of intervention research has been conducted to assess the viability of the teacher and coach education programs designed to enhance motivation from an achievement goal perspective (i.e., Lloyd & Fox, 1992; Solmon, 1996; Treasure & Roberts, 2001). Comparing two different approaches to teaching an aerobics/fitness class to adolescent females, Lloyd and Fox found that participants in the mastery condition reported higher motivation to continue participating in aerobics and more enjoyment than those who participated in the performance condition. Consistent with the findings of Lloyd and Fox, Solmon found that seventh and eighth-grade students who participated in the mastery condition demonstrated more willingness to persist in a difficult juggling task than those in the performance condition. In addition, students in the performance condition were more likely to attribute success during the intervention to normative ability than those in the mastery condition. This finding is consistent with Nicholls’s (1989) contention that achievement goals and beliefs about success are conceptually linked.

Similar to the intervention designed by Solmon (1996), Treasure and Roberts (2001) drew on strategies suggested by Ames (1992a, 1992b, 1992c) to promote either a mastery or a performance climate. The strategies were then organized into the interdependent structures that Epstein (1988, 1989) has argued define the achievement context: task, authority, recognition, grouping, evaluation, and time structures, better known by the acronym TARGET. Responses of female and male young adolescent physical education students suggest that a teacher can influence the salience of a mastery or performance climate and, in so doing, affect a child’s motivation in physical education. Although the results of the studies conducted by Solmon and Treasure and Roberts indicate that adopting and adapting classroom-based intervention programs in the context of physical education may be effective, it is important to recognize that there may be significant differences between achievement contexts. This point is even more important when one considers the achievement context of youth sport. In assessing and implementing interventions to enhance the quality of motivation in youth sport, therefore, researchers need to be sensitive to differences between the achievement contexts (Nicholls, 1992).

The few intervention studies that have been conducted clearly show that a mastery climate has positive behavioral, cognitive, and affective outcomes. All of the studies conducted to date, however, have been short term and limited in what they assess. Randomized, controlled studies over time are needed to truly assess the causal role of motivational climates on motivational outcomes.

The Hierarchical Approach To Achievement Goals

One of the most provocative attempts at revising and extending achievement goal theory in the past decade has emerged from work on the hierarchical model of achievement motivation (Elliot, 1999). This model is based on the premise that approach and avoidance motivation represent fundamentally different strivings. The approach-avoidance distinction has a long intellectual history (Elliot & Covington, 2001) and was considered in early writing on achievement goals (e.g., Nicholls, 1984, p. 328) but, until recently, was largely neglected in subsequent empirical work.

Briefly, the hierarchical model of achievement motivation asserts that dynamic states of achievement goal involvement are influenced by (a) stable individual differences (e.g., motives, self-perceptions, relationally based variables, neurophysiologic predispositions; Elliot, 1999) and (b) situational variables (e.g., motivational climate; Ames, 1992c; Ames & Archer, 1988). In turn, these dynamic states of goal involvement are posited as direct predictors of achievement processes and outcomes. A complete presentation of the hierarchical model of achievement motivation is beyond the scope of this article (see Elliot, 1999). Instead, we focus on a major implication of the premise that approach and avoidance motivation are fundamentally different—specifically, the implication that approach-valenced achievement goals may be distinguished (both conceptually and empirically) from avoidance-valenced achievement goals.

An Expanded Model of Achievement Goals

As described earlier in this article, the prevailing models of achievement goals in the educational, industrial-organizational, social, and sport literatures have been dichotomous in nature. Goals are distinguished largely (but not always exclusively) on how competence is defined. From this perspective, competence could be defined in task-referential terms (e.g., How well did I perform this task in relation to how well it could possibly be performed?), in self-referential terms (e.g., How well did I perform this task in relation to my previous performances?), or in normative terms (e.g., How well did I perform this task in relation to others?). Due to their conceptual and empirical similarities, the vast majority of research combined task and self-referential definitions of competence into a single task, or mastery, goal. Normative definitions of competence have typically been designated as ego, or performance, goals. We use the terms mastery and performance to refer to the goals in the hierarchical model.

In the mid-1990s, several scholars working in parallel (e.g., Elliot, 1997; Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996; Middleton & Midgley, 1997; Skaalvik, 1997; Skaalvik & Valas, 1994) returned to the possibility that individuals may sometimes focus on striving not to be incompetent as much as or more than they are striving to be competent. In achievement situations, competence and incompetence are outcomes that individuals typically find appetitive and aversive, respectively. Thus, it is possible to differentiate goals based on their valence, or the degree to which the focal outcome is pleasant or unpleasant.

In reviewing the achievement goal literature, Elliot (1994) observed that performance goals that focused on the pleasant possibility of competence (approach goals) led to different outcomes from performance goals focused on the unpleasant possibility of incompetence (avoidance goals). A meta-analysis of the motivation literature revealed that goal valence moderated the effects of performance goals on participants’ intrinsic motivation (Rawsthorne & Elliot, 1999). Performance-avoidance goals reduced both free-choice behavior and self-reported interest in a task, whereas performance-approach goals did not have any consistent effect on either intrinsic motivation index. This finding led to the introduction of a tripartite model of achievement goals comprising mastery, performance-approach goals, and performance-avoidance goals (Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996). In the first empirical test of this tripartite model, the valence of performance goals moderated relations between the goals and relevant antecedents (e.g., achievement motives, competence expectations, sex) and consequences (e.g., intrinsic motivation). A subsequent series of studies extended understanding of how the valence of performance goals can moderate relations between goals and achievement processes and outcomes (e.g., Cury, Da Fonséca, Rufo, Peres, & Sarrazin, 2003; Cury, Da Fonséca, Rufo, & Sarrazin, 2002; Cury, Elliot, Sarrazin, Da Fonséca, & Rufo, 2002; Elliot & Church, 1997; Elliot & McGregor, 1999).

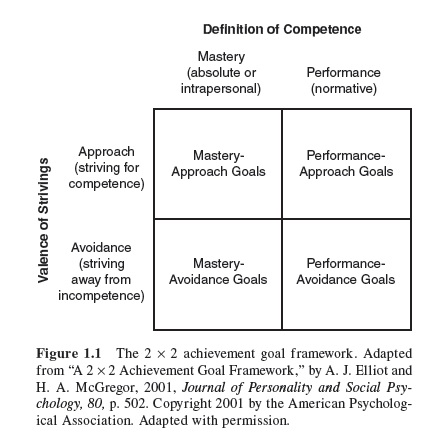

Thus, the argument was proffered that achievement goals should consider both the definition of competence and the valence of the striving, and the model was expanded to include a fourth possible achievement goal: mastery avoidance goals (Elliot, 1999; Elliot & Conroy, 2005). As seen in Figure 1.1, the two definitions of competence (i.e., mastery/task versus performance/ego) and two valences of strivings (i.e., approaching competence versus avoiding incompetence) yield a 2 × 2 model of achievement goals comprising mastery approach, mastery-avoidance, performance-approach, and performance-avoidance goals. These goals can be assessed with the 2 × 2 Achievement Goal Questionnaire for Sport (Conroy, Elliot, & Hofer, 2003).

Mastery-approach (MAp) goals focus on performing a task as well as possible or surpassing a previous performance on a task (i.e., learning, improving). They are equivalent to existing conceptions of mastery or task goals in the dichotomous model of achievement goals. They are expected to be the optimal achievement goal because they combine the more desirable definition of competence with the more desirable valence. In sport settings, these goals are extremely common because they are directly implicated in individuals’ striving for personal records and peak performances as well as skill acquisition processes.

Performance-approach (PAp) goals focus on outperforming others. They are equivalent to existing conceptions of performance or ego goals in the dichotomous model of achievement goals. These goals may be adaptive when, as noted earlier, they are accompanied by a high perception of competence. However, in the 2 × 2 model, PAp goals are expected to be suboptimal because of their performance definition of competence, but not entirely dysfunctional because they are valenced toward competence. PAp goals are probably especially salient because of the social comparison processes inherent in sport and other competitive activities.

Performance-avoidance (PAv) goals focus on not being outperformed by others. As described previously, PAv goals provided the impetus to consider how the valence of goals might enhance the predictive power of the goal construct. They are expected to be the most dysfunctional of all achievement goals because they combine the less desirable definition of competence with the less desirable valence. These goals may be expressed when individuals are concerned about losing a contest or appearing incompetent in comparison with others.

Mastery-avoidance (MAv) goals focus on not making mistakes or not doing worse than a previous performance. As the latest addition to the achievement goal family, relatively little is known about these goals. They combine adesirable definition of competence with an undesirable focus on avoiding incompetence, so they are expected to exhibit a mixed set of consequences. Elliot (1999; Elliot & Conroy, 2005; Elliot & McGregor, 2001) has theorized that these goals may be particularly relevant for perfectionists striving for flawlessness, for athletes focused on maintaining their skill level as they near the end of their careers, and for older adults fighting off the natural functional declines associated with aging.

Figure 1.1 The 2 × 2 achievement goal framework. Adapted from “A 2 × 2 Achievement Goal Framework,” by A. J. Elliot and H. A. McGregor, 2001, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, p. 502. Copyright 2001 by the American Psychological Association. Adapted with permission.

Antecedents and Consequences of 2 × 2 Goal Adoption

Considering that the vast majority of the recent achievement motivation literature in sport has implicitly focused on approach goals (i.e., MAp, PAp), relatively little is known about the correlates and consequences of avoidance-valenced achievement goals in sport. This section reviews documented links between the four goals in the 2 × 2 framework and theoretically relevant antecedents and consequences (e.g., achievement processes and outcomes). The vast majority of the research on goals in the 2 × 2 framework resides outside of the sport and exercise psychology literature. Rather than relying exclusively on the nascent sport psychology literature on 2 × 2 goals, we include selected findings from broader social and educational psychology literatures in this review. There is also some conceptual confusion about whether some variables (e.g., competence valuation) belong as antecedents or consequences of different states of goal involvement; they are listed according to how they were conceptualized in their respective studies.

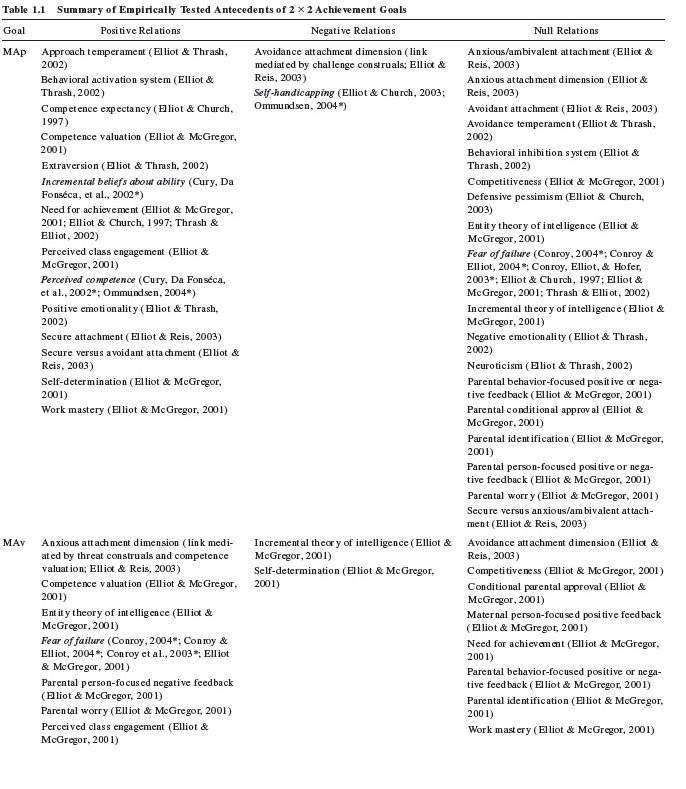

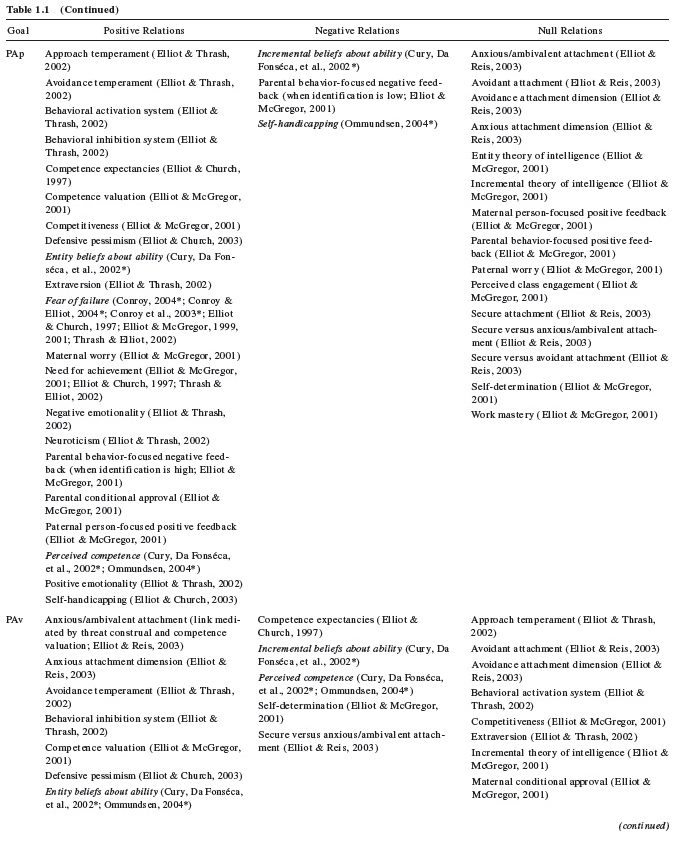

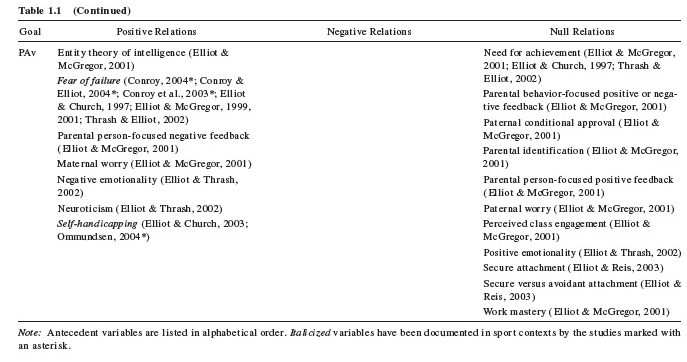

Antecedents of 2 × 2 Achievement Goals

Empirically-tested antecedents of the four achievement goals are summarized in Table 1.1 based on whether the antecedents have demonstrated positive, negative, or null relations with each goal. These links are based on bivariate relations between each antecedent and the goal; relatively few relations change when third variables (e.g., ability) have been controlled.

Common antecedents of MAp goal involvement appear to include appetitive motivational dispositions (e.g., motives, temperament), positive self-perceptions (e.g., competence and attachment-related perceptions), and perceived situational importance (e.g., competence valuation, class engagement). On the other hand, aversive motivational dispositions and negative cognitive representations of self and others do not appear to be associated with MAp goal involvement.

Mastery-avoidance goal involvement appears to be linked to antecedents such as negative perceptions of self and others (e.g., anxious attachment, fear of failure), entity rather than incremental theories of intelligence, reduced self-determination, and perceived situational importance. Appetitive motive dispositions do not appear to be MAv goal antecedents.

Common antecedents of PAp goal involvement include both appetitive and aversive motivational dispositions, competence perceptions, and entity rather than incremental theories of ability. Attachment security and self-determination do not appear to be PAp goal antecedents.

Finally, PAv goal involvement appears to be linked to antecedents such as avoidance motivational dispositions, reduced competence expectations, more entity and fewer incremental beliefs about ability, and less self-determination. Appetitive motivational dispositions and attachment security do not appear to be PAv goal antecedents.

Overall, socialization processes (e.g., perceived parenting practices) were not consistently associated with the achievement goals adopted by participants. This finding should be expected because socialization processes are more likely to have direct effects on more stable individual differences (e.g., motives) than on dynamic constructs such as goals.

Consequences of 2 × 2 Achievement Goals

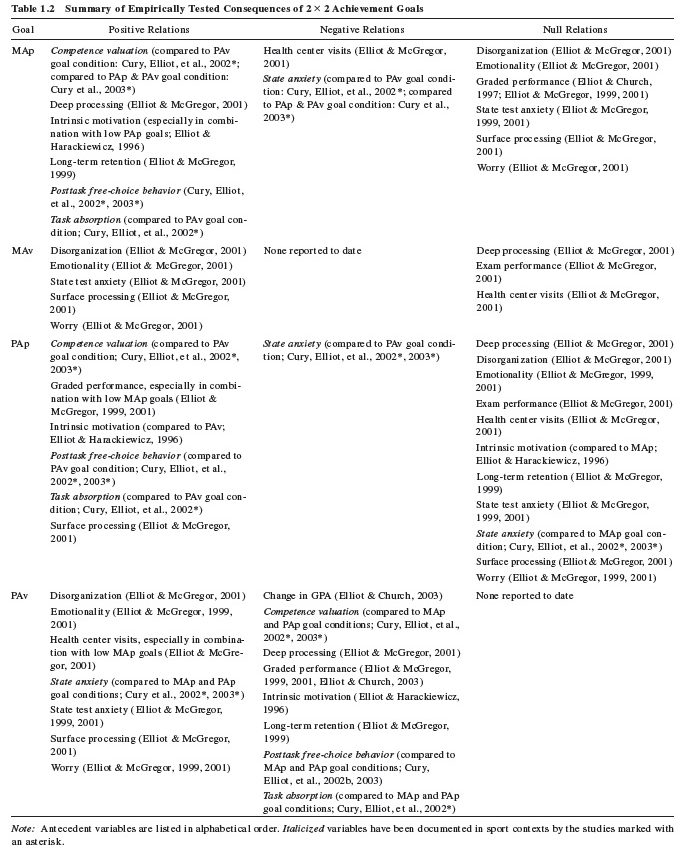

Table 1.2 summarizes consequences of 2 × 2 achievement goals from previous research. Given that empirical tests of the 2 × 2 model are in their early stages, conclusions drawn here should be interpreted with appropriate caution. Special attention should be given to the studies that experimentally manipulated participants’ goals (e.g., Cury, Da Fonséca, et al., 2002; Cury, Elliot, et al., 2002; Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996) because such manipulations provide a much stronger demonstration of the causal role theorized for these goals than do passive observation designs (particularly when data are collected at a single occasion from a single source).

Mastery-approach goals appear to be associated with the optimal set of consequences (e.g., enhanced intrinsic motivation and information processing, reduced anxiety, fewer health center visits). Strikingly, MAp goals have not been linked to superior performance on cognitive tasks. Mastery-avoidance goals were linked with a generally undesirable set of achievement processes (e.g., anxiety, disorganization, surface processing) but did not seem to be associated with undesirable outcomes (e.g., performance, health center visits). Performance-approach goals were the only goals to be positively associated with superior performance. These goals also were linked with a partial set of desirable (e.g., more absorption, competence valuation, and intrinsic motivation; less anxiety) achievement processes and were not associated with any undesirable achievement processes. Finally, PAv goals were consistently linked with the most undesirable achievement processes and outcomes of all four goals. Based on these results, MAp goals appear to be optimal, PAv goals appear to be dysfunctional, and both PAp and MAv goals are neither entirely optimal nor entirely dysfunctional (with the former appearing to be more optimal than the latter).

Table 1.1 Summary of Empirically Tested Antecedents of 2 × 2 Achievement Goals

Table 1.1 Summary of Empirically Tested Antecedents of 2 × 2 Achievement Goals

Critical Issues Regarding 2 × 2 Achievement Goals

Elliot and colleagues (e.g., Elliot, 1997, 1999; Elliot & Conroy, 2005; Elliot & Thrash, 2001, 2002) argue that on both theoretical and empirical grounds, the 2 × 2 model of achievement goals has demonstrated promise for enhancing understanding of achievement motivation. Nevertheless, research on this model in sport contexts has been limited, and further research is required to demonstrate its veracity and potential. Research linking goals, particularly avoidance goals, to hypothesized patterns of antecedents and consequences in sport would be a useful first step in this process. Following are some other issues that will need to be addressed in future research.

Controversy still exists over whether the approach avoidance distinction merely represents differences in perceptions of competence, especially for the performance dimension. That is, do perceptions of competence moderate relations between goals and various consequences, and if so, would it not be simpler to omit the valence dimension from the goals model? From a conceptual standpoint, the hierarchical model of achievement motivation frames perceptions of competence as antecedents of achievement goals because high perceptions of competence orient individuals toward the possibility of success and low perceptions of competence orient individuals toward the possibility of failure (Elliot, 2005). From an empirical perspective, Elliot and Harackiewicz (1996) have found that perceived competence failed to moderate the effects of any of their tripartite goal manipulation contrasts (i.e., mastery, PAp, PAv) on intrinsic motivation, and all of their main effects for the goal manipulations remained significant with the moderator terms in the model. Based on such evidence, it is argued by Elliot and colleagues that the valence dimension of achievement goals does not appear to be a proxy for perceived competence on either conceptual or empirical grounds.

This approach does not rule out the possibility that individual differences in goal antecedents (e.g., achievement motives) may moderate the effects of the goals on various consequences. For example, PAp goal involvement has been linked to both appetitive and aversive achievement motives (need for achievement and fear of failure, respectively). It is possible that PAp goals energized by the appetitive motive may yield different consequences than would PAp goals that are energized by the aversive motive. A three way Goal × Motive × Feedback interaction also is conceivable, as PAp goals may change differentially for individuals with different motive dispositions following failure/success feedback. These cross-level interaction hypotheses are open empirical questions.

Table 1.2 Summary of Empirically Tested Consequences of 2 × 2 Achievement Goals

Table 1.2 Summary of Empirically Tested Consequences of 2 × 2 Achievement Goals

Next, it will be important to capture the dynamic features of the goals construct to strengthen claims about the causal effects of goals on achievement processes and outcomes. Some argue that relying on dispositional conceptualizations of goals is inappropriate in the hierarchical model of achievement motivation, but researchers can vary the temporal resolution of their goal assessments. Some studies may assess goals for an event and track processes and outcomes over the course of the event to use in prospective prediction models (e.g., using preseason goals to predict changes in relevant outcomes over the course of the season). Other studies may assess goals, processes, and outcomes on more of a moment-to-moment basis (even though this is difficult to do, as we noted earlier) to capture dynamic links between goals and their consequences (e.g., using daily goals to predict daily fluctuations in relevant outcomes over the course of the season). Both approaches will be valuable provided that the temporal resolution of the goal assessment is clear when interpreting the results.

Finally, whereas a great deal of data has accumulated about individual difference antecedents of different achievement goals, relatively little is known about the situational factors that antecede 2 × 2 goals. Church, Elliot, and Gable (2001) reported differences in classroom environments that predicted students’ tripartite goals. There are few published studies regarding links between situational characteristics and 2 × 2 goal involvement in sport, except research based on achievement goal theory investigating motivational climate that indirectly informs performance and mastery achievement striving (for an exception see Conroy, Kaye, & Coatsworth, 2006).

Reflections On The Hierarchical Model And Achievement Goal Theory

The introduction of the hierarchical model has challenged many of the tenets and underlying assumptions of what may be referred to as traditional achievement goal theory. One of the most important challenges and differences between the perspectives pertains to the energization of the motivational process. As we have seen, the hierarchical model differentiates goals based on both the definition of competence (a similarity with the dichotomous model) and their valence or the degree to which the focal outcome is pleasant or unpleasant (a difference between the models). The argument is that achievement goals should consider both the definition of competence and the valence of the striving. However, it may be argued that in the hierarchical model we seem to be defining achievement goals as discrete goals based on a definition of competence and achievement strategies aimed at fulfilling some particular objective. In the hierarchical model, goals are midlevel constructs that mediate the effects of a host of individual differences (e.g., achievement motives, self-perceptions, relational variables, demographic characteristics, neurophysiologic predispositions) and situational factors (e.g., norm-based evaluation) on specific motivated behaviors and serve as proximal predictors of achievement-related processes and outcomes (Elliot, 1999). But it is the appetitive (approach) and aversive (avoidance) valence of competence striving that energizes the motivational process. It is assumed that the goals are the manifestation of needs, or at least the “motivational surrogates,” as Elliot and Church (1997) state of the needs of achievement motivation (approach) and the fear of failure (avoidance; Kaplan & Maehr, 2002). This suggests that achievement goals represent approaches to self-regulation based on satisfying approach and avoidance needs that are evoked by situational cues. Achievement goals arise from affect-based objectives, at least in part, in the hierarchical model.

In traditional achievement goal theory, it is the goals themselves that are the critical determinants of achievement cognition, affect, and behavior. It is the goals that give meaning to the investment of personal resources because they reflect the purposes underlying achievement actions in achievement contexts. Once endorsed, the goal defines an integrated pattern of beliefs, attributions, and affect that underlie approach and avoidance strategies, different levels of engagement, and the different responses to achievement outcomes (Duda & Hall, 2001; Kaplan & Maehr, 2002). The way an individual interprets his or her performance can be understood in terms of what an individual considers to be important in a particular context and his or her beliefs about what it takes to be successful in that situation. Achievement goals refer to achievement-oriented or achievement-directed behavior where success is the goal. Nicholls (1989) argued that these beliefs and perceptions form a personal theory of achievement in the activity that drives the motivation process, and that a conceptually coherent pattern of relationships should therefore existbetween an individual’s achievement goals (the subjective meaning of success) and his or her achievement striving. In the achievement goal approach, it is not how one defines competence with its attendant valence; it is how one defines success and the meaning of developing or demonstrating competence. Thus, the hierarchical approach presents energizing constructs that are different. The conceptual argument is whether we need “needs” to explain the energization of the motivational equation, or whether we can accept a cognitive theory of motivation that focuses on thoughts and perceptions as energizing motivated behavior (Maehr, 1987). We need more empirical investigation of the conceptual energizing constructs, and their roles, underlying achievement striving in achievement contexts to better understand the motivational equation.

One other conceptual difference has emerged from the development of measures for the hierarchical model of goals, especially of the 2 × 2 model in sport. Duda (2005) has argued that because the interrelationships between the performance-approach, mastery-avoidance, and performance-avoidance goals is low to moderate (e.g., Conroy et al., 2003), and only the mastery-approach and performance-avoidance goals have demonstrated independence, this creates conceptual problems for the hierarchical approach. How does this relate to the evidence that task and ego goals have been demonstrated to be orthogonal in the dichotomous achievement goal approach, at least from the Maehr and Nicholls approaches (e.g., Maehr & Braskamp, 1986; Maehr & Nicholls, 1980; Nicholls, 1989)? More research is clearly needed to explore this issue as proponents of the 2 × 2 model argue that limited positive correlations should be expected between goals that share either a definition of competence or a valence. However, this raises interesting questions: What are the expected relationships between the goals? Should they demonstrate greater independence to be recognized as extending the range of goals?

In addition, there is evidence that the hierarchical model may have different assumptions underlying performance approach and avoidance goals. Performance-approach tendencies may be based on demonstrating normative ability and defining competence in normative terms, but recent research has suggested that performance-avoidance may be based on one of three facets: impression management, or “saving face” (Skaalvik, 1997; Skaalvik & Valas, 1994); a fear of failure (Elliot & Church, 1997); or a focus on avoiding demonstrating low ability (Middleton & Midgley, 1997). In an interesting study investigating the measurement technology underlying the hierarchical model, Smith, Duda, Allen, and Hall (2002) wished to determine whether the different measures used were measuring the same constructs. They found that impression management (Skaalvik,1997) explained the most variance (40%), with fear of failure (Elliot & Church, 1997) and avoiding demonstrating low ability (Middleton & Midgley, 1997) explaining only 9.4% and 8% of the variance, respectively. It would seem important for future research to clarify the conceptual underpinnings of performance-avoidance: What parts are played by fearing failure, avoiding demonstrating low ability, and protecting self-worth? Given the findings of Smith and colleagues, perhaps it is more important to performance-avoiding people to protect self-esteem rather than be motivated to avoid failing. What is the role the protection of self-worth plays? When individuals begin to question their ability to present a positive sense of self, are they more likely to favor avoidance strategies?