Variations in physical growth are readily observable in our daily interactions with people. We each possess unique characteristics in terms of our height, weight, body proportions, and physical fitness. Additionally, our capacities to engage in various physical activities and tasks vary considerably. These observable distinctions offer a window into our maturation, broader developmental trajectory, and state of health. Consequently, the exploration of physical growth and development occupies a pivotal place in the realms of child development, healthcare, education, and an array of other interdisciplinary fields. Furthermore, it holds personal significance for every individual who inhabits a corporeal form.

The study of physical growth and development encompasses a vast spectrum of phenomena, from the intricate processes that drive a child’s growth spurt to the maintenance of physical well-being throughout the lifespan. It unveils the secrets of human biology, unfolding the narratives of how our bodies evolve and adapt to life’s myriad challenges.

Child Development: Physical growth is profoundly intertwined with child development. The remarkable transformations in height, weight, and body proportions throughout childhood are markers of progress, reflecting the intricate interplay of genetic predispositions, nutritional factors, and environmental influences. These changes aren’t just markers of age but provide valuable insights into the health and well-being of a child.

Medicine: In the realm of medicine, an understanding of physical growth is paramount. Physicians track the growth trajectories of children to assess their overall health. Deviations from the expected patterns can signal underlying health issues that require attention. Moreover, the study of physical growth underpins areas like pediatrics, orthopedics, and endocrinology, contributing to advancements in healthcare.

Education: Physical development isn’t confined to biological aspects alone; it also extends to motor skills and physical abilities. In the educational domain, educators and physical education specialists leverage insights into physical growth to tailor curricula that support the development of fine and gross motor skills. These skills are pivotal for a child’s academic success and overall well-being.

Interdisciplinary Relevance: The significance of studying physical growth transcends disciplinary boundaries. It resonates within diverse fields such as psychology, nutrition, sociology, and anthropology. These disciplines draw upon research in physical development to unravel the complex interplay of nature and nurture, genetics and environment, which shape our physical selves.

Personal Connection: Beyond its academic and professional implications, physical growth is a subject of intrinsic interest to every individual inhabiting a corporeal form. We each embark on a unique journey of growth and transformation, experiencing the ebbs and flows of physical change as we progress through life. Understanding our own physical development can foster a deeper connection with our bodies and promote practices that enhance our health and well-being.

In sum, the study of physical growth and development is not merely an academic pursuit; it is a dynamic, multidisciplinary field that illuminates the tapestry of human existence. It enables us to decode the enigmatic processes that underlie our physicality, from the wonder of a child’s growth to the maintenance of health and vitality in adulthood and beyond. Whether for professionals dedicated to enhancing the lives of others or individuals on a personal journey of self-discovery, the study of physical growth offers a gateway to understanding the intricate dance of biology, environment, and human potential.

Stages Of Physical Growth

While there is a common overarching pattern to physical growth shared by all individuals, the specific trajectory can vary significantly in terms of growth rate, timing, and ultimate size achieved. Chronological age serves as a convenient reference point for monitoring and documenting growth. However, it’s essential to recognize that biological events and processes operate on their distinct timetables. As the adage goes, biology doesn’t conform to birthday celebrations!

Let’s delve deeper into the stages of physical growth:

**1. Infancy:

- The Rapid Ascent: The journey of physical growth commences at birth. During infancy, growth is nothing short of astonishing. Babies typically double their birth weight within the first five months and triple it by their first birthday.

- Height and Head Circumference: Alongside weight gain, increases in height and head circumference are notable markers. The development of fine and gross motor skills also emerges during this phase.

2. Childhood:

- Steady Growth: In childhood, growth becomes steadier but no less impressive. Children gain an average of 2 to 2.5 inches in height per year and put on around 5 pounds of weight annually.

- Proportionality: Body proportions shift, with the legs growing relatively faster than the trunk. This contributes to the characteristic appearance of childhood, with its shorter legs and longer torso compared to adulthood.

3. Adolescence:

- The Growth Spurt: Adolescence heralds the most dramatic phase of growth— the adolescent growth spurt. This period is characterized by a rapid increase in height, often accompanied by significant weight gain.

- Secondary Sexual Characteristics: The growth spurt aligns with the development of secondary sexual characteristics, such as breast development in females and the deepening of the voice in males. Hormones, particularly estrogen and testosterone, play pivotal roles in these transformations.

4. Adulthood:

- The Plateau: Growth in terms of height largely ceases by late adolescence or early adulthood when epiphyseal growth plates in the long bones close. However, growth in muscle mass and body composition continues to evolve throughout adulthood.

- Maintenance and Decline: Early adulthood is marked by the peak of physical abilities, including strength and endurance. As individuals progress through middle and late adulthood, there is typically a gradual decline in muscle mass and physical performance. Bone density may also diminish, contributing to age-related conditions like osteoporosis.

5. Late Adulthood:

- The Golden Years: Late adulthood, often referred to as the “golden years,” is characterized by a range of physical changes. These can include a decrease in bone density, muscle mass, and skin elasticity.

- Health and Wellness: The maintenance of good health practices, such as regular exercise and a balanced diet, can mitigate some of the physical effects of aging and promote overall well-being.

Throughout these stages, it’s essential to remember that while chronological age serves as a useful reference point, individual variability is substantial. Biological rhythms may result in early bloomers or late bloomers, emphasizing that each person’s journey of physical growth is unique. Understanding these stages not only informs us about the fascinating biology of human development but also offers insights into promoting health and well-being across the lifespan.

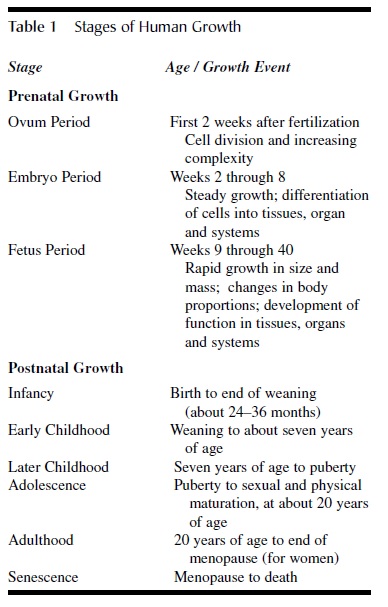

Table 1 Stages of Human Growth

Table 1 Stages of Human Growth

Table 1: Stages of Human Physical Growth

This table offers a concise overview of the various stages of human physical growth, along with typical ages and significant events associated with each stage. It’s important to note that any model of developmental stages is inherently somewhat arbitrary. The model presented here provides one perspective on understanding the continuum of physical growth, spanning from conception to the end of life.

Prenatal Growth

Prenatal growth is a fascinating journey that encompasses approximately 9 months or 40 weeks of intricate biological transformations. Understanding this process is essential not only for academic curiosity but also for medical practice and parental insight. There are two common approaches for categorizing prenatal growth: one that focuses on the development of the organism as an ovum, an embryo, and a fetus, and the other that divides pregnancy into trimesters, each comprising 3-month periods. While the trimester model is useful for clinical purposes, it offers only a broad approximation of the intricate biological events occurring during this crucial period. Therefore, this discussion will delve into prenatal growth in terms of biological events, particularly highlighting the development of the ovum, the embryo, and the fetus.

The Ovum: The Starting Point of Life

The journey of prenatal growth commences with conception, where the father’s sperm fertilizes the mother’s egg, known as the ovum. This phase, known as the period of the ovum, encompasses the initial two weeks following fertilization. During this period, a remarkable process of self-duplication and multiplication unfolds, transforming a single cell into tens of thousands of new cells. As cell division proceeds, the cluster of cells undergoes intriguing transformations, evolving from a structure resembling a raspberry into a hollow disk. By the end of the second week following fertilization, this disk firmly attaches itself to the uterine wall, embarking on a journey of cellular differentiation, ultimately leading to the development of the embryo.

The Embryo: Forming the Blueprint of Life

The embryo period, commencing in the second week after fertilization, is marked by rapid growth and the differentiation of cells. During this phase, cells begin to specialize and organize, giving rise to distinct tissues, organs, and bodily systems. By the eighth week, the embryo has laid the foundation for the fundamental physical and functional attributes of a human being. Subsequent weeks predominantly witness refinements in physical features, as no new anatomical features emerge beyond this point. This early phase of life is exceptionally sensitive to growth pathologies arising from genetic abnormalities or adverse environmental conditions, including maternal malnutrition or disease.

The Fetus: A Remarkable Phase of Maturation

Entering the fetal phase around week 9, the process of differentiation and specialization into tissues, organs, and bodily systems is largely finalized. Rapid growth becomes the hallmark of this period, especially from week 20 onward. Astonishingly, about 90% of the body weight at birth is achieved during this latter half of pregnancy. Furthermore, the fetus undergoes significant changes in body proportions, transitioning from an embryo with a disproportionately large head to a more recognizably human form as the back and limbs grow rapidly relative to the head.

Importantly, this phase prepares the fetus for the transition to life outside the mother’s womb by developing critical bodily systems, such as blood circulation, breathing, and digestion. These intricate changes ensure the fetus’s readiness for survival and growth in the outside world.

In summary, prenatal growth is a remarkable journey that spans the stages of the ovum, embryo, and fetus. Each phase is characterized by distinct biological events, contributing to the awe-inspiring process of human development from conception to the dawn of life. Understanding these stages is not only a matter of scientific intrigue but also a source of profound insight into the miracle of human existence.

Postnatal Growth— The Growth Curve

The exploration of postnatal growth and the inception of the renowned growth curve can be traced back to 18th-century France, where Count Philibert Gueneau de Montbeillard embarked on an extraordinary journey. Count Montbeillard meticulously measured his son’s height every six months, starting from birth until the young age of 18. These measurements, initially recorded for familial interest, became a treasure trove of data for scientific discovery thanks to his close friend, the esteemed scientist George-Louie Leclerc de Buffon.

Montbeillard’s act of measuring his son’s height at regular intervals marked a revolutionary approach to understanding physical growth. Prior to this development, the predominant method for assessing growth relied on cross-sectional studies, which involved measuring individuals only once. However, this approach had a fundamental limitation—it couldn’t shed light on the individual’s growth trajectory from one year to the next. Yet, it was precisely this information, detailing variations and shifts in growth rates, that held significant value for clinicians seeking to compare an individual’s growth rate to established standards and for researchers exploring the intricate relationship between early influences and subsequent physical development.

One notable challenge with Montbeillard’s original measurements was their use of antiquated French units, which hindered widespread comprehension and application. It wasn’t until the early 20th century that an American named Richard Scammon undertook the task of converting these measurements into the modern metric system. His efforts gave birth to an invaluable resource in the form of growth charts that are now indispensable tools in the study of physical growth.

Today, we recognize the enduring accuracy of Montbeillard’s measurements and their revelation of distinct growth phases that continue to hold true. Despite the technological strides of recent years, these early observations serve as a testament to the enduring importance of understanding the intricate journey of postnatal growth.

Phases of Postnatal Growth and Development

Scammon’s pioneering chart, meticulously detailing a boy’s height from birth to age 18, is what we refer to as a distance curve. It aptly maps out the journey toward physical maturity, offering profound insights into the intricacies of postnatal growth and development. This curve unveils several key facts about the process.

First and foremost, it’s abundantly clear that the first 18 years of life are marked by dramatic growth. However, this growth is far from linear. Each year doesn’t bring an equal increase in height, and there are periods of rapid growth interspersed with phases of relatively slower expansion. While the distance curve hints at these distinct growth stages, it doesn’t provide a precise delineation. To truly capture the nuances of varying growth rates over time, we turn to the velocity curve, a vital tool for this purpose.

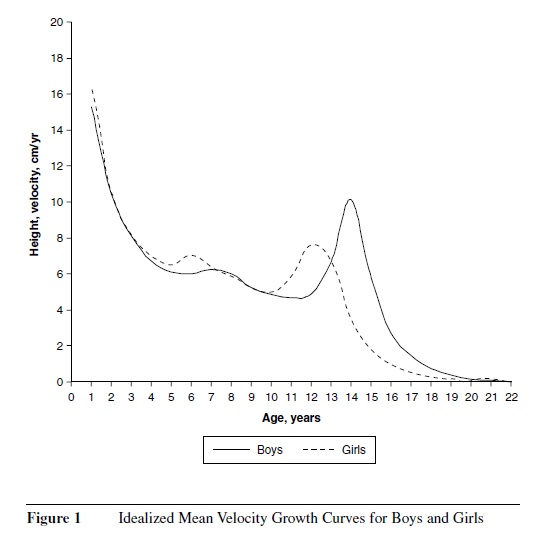

The idealized velocity curve, as depicted in Figure 1, immediately reveals the existence of discrete phases in physical growth. Two notable spurts stand out, with the first occurring around 6 to 8 years of age, and the second, more extended one commencing at approximately 10 years for girls and 12 years for boys. By scrutinizing these shifts in growth rates, we can methodically divide postnatal growth into distinct phases. Each phase boasts its unique growth events and processes, contributing to the fascinating mosaic of human development.

It’s essential to acknowledge that while the fundamental pattern of human growth remains constant, there exist significant variations in individual growth rates and timing across the lifespan. This isn’t just an academic curiosity; it holds practical implications. Consider a classroom of 12-year-old girls or 14-year-old boys—here, educators encounter students spanning a vast spectrum of physical maturity. From relatively immature children to nearly grown adults, these differences underscore the diverse journeys of postnatal growth that shape each individual.

Figure 1 Idealized Mean Velocity Growth Curves for Boys and Girls are almost adults.

Infancy

Infancy, that remarkable phase of human life, commences with the moment of birth and gracefully concludes when the infant embarks on the journey from nourishing breast milk to embracing solid sustenance. The age at which this transition unfolds may vary across societies, influenced by cultural practices, and further complicated by the contemporary trend in industrialized nations to curtail or eliminate breastfeeding periods. In societies rooted in tradition, providing a more steadfast benchmark, weaning typically concludes around the age of 2 or 3.

The neonatal period, comprising the initial months following birth, serves as a bridge from the cozy confines of the womb to the wide expanse of the external world. Infancy, then, marks a period of dynamic transformation. It is a time of rapid growth across most physical dimensions and bodily systems. However, this period is characterized by a notable deceleration in growth velocity, giving it a unique rhythm. In many aspects, the growth patterns of infancy echo the trajectory set during fetal development.

In these earliest years, not only do height and weight experience significant augmentation, but there’s also a recalibration of body proportions. Perhaps the most conspicuous feature of this phase is the relatively large head, representing a staggering 25% of the total body length and nearing 70% of its eventual adult size. As the first year unfolds, the head’s proportion to body length recedes to 20%, while adulthood sees it shrink further to a mere 12%. During this evolution, the legs assert themselves, commanding a substantial 50% of the total stature, reflecting the profound physical metamorphosis that characterizes infancy.

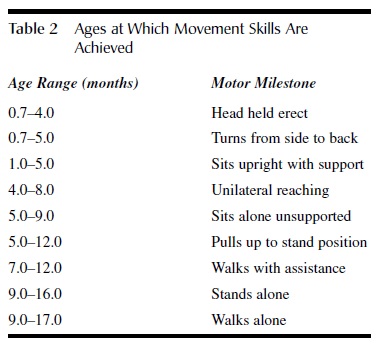

Table 2 Ages at Which Movement Skills Are Achieved

Table 2 Ages at Which Movement Skills Are Achieved

Infancy emerges as a pivotal chapter in human development, heralding the inception of the musculoskeletal framework and the nervous system, particularly the brain. Among all bodily tissues and organs, the brain stands out during this period, experiencing a growth spurt unmatched at any other point in life. This surge in development lays the groundwork for a plethora of cognitive and motor accomplishments. In these nascent stages, most movements are characterized by reflex actions, defined as involuntary responses triggered by a range of external stimuli.

As the infant inches closer to the 12 to 24-month mark, a transformative phase ensues. This period serves as a platform for the child to not only hone the skills initiated during the first year but also to acquire new ones. While the rate of skill acquisition may exhibit individual variance, the sequence of skill acquisition remains remarkably consistent and appears to transcend social, cultural, and ethnic boundaries. The groundwork for understanding these milestones was laid during the 1930s and 1940s, with researchers defining crucial “motor milestones.” These milestones serve as cornerstones in an infant’s movement development, each skill representing a landmark achievement (see Table 2).

Early Childhood

In the wake of the measured pace of growth during infancy, the years spanning from 3 to 7 usher in a period of comparatively rapid physical development. A hallmark feature of early childhood growth is its striking predictability, with a uniform pattern observable among most healthy children. This predictability has proven invaluable in clinical and epidemiological contexts, as deviations from the norm can flag potential health concerns.

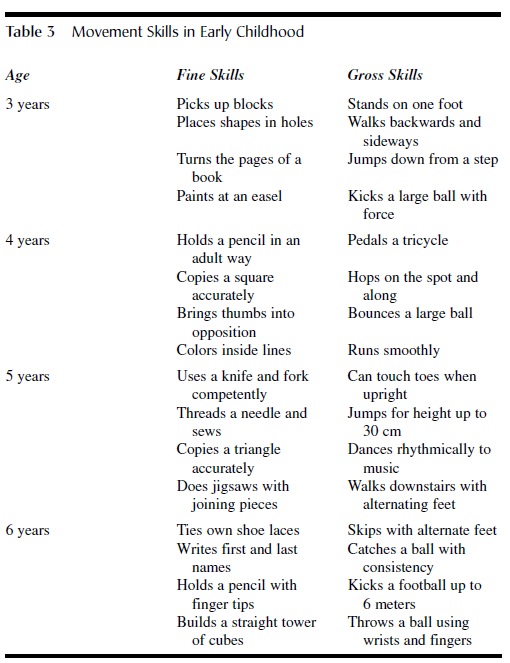

While children at this age have transitioned from breastfeeding to solid foods, they continue to rely heavily on adult support, primarily due to their ongoing cognitive and motor development. Early childhood serves as a critical juncture for mastering fundamental motor skills and testing one’s physical mettle in diverse environments. Movement activities can be dissected through various lenses, yet most fall into the overarching categories of stability (or balance), locomotion (or movement), and manipulation (or control). These categories are foundational across all age groups. Furthermore, movement activities can be further classified into fine motor and gross motor activities. Fine motor activities necessitate precision and dexterity, often coordinating the use of hands and eyes in activities like writing, drawing, cutting, pasting, and handling small objects and tools. On the other hand, gross motor activities involve the entire body or significant body segments and encompass fundamental motor skills such as running, jumping, twisting, turning, hopping, throwing, and kicking (refer to Table 3 for a comprehensive list).

Later Childhood

The transition from early childhood to later childhood often witnesses an increase in growth velocity, aptly named the midgrowth spurt. Subsequently, from around 7 years of age until the onset of puberty, there is a gradual decline in the rate of growth. This phase marks the slowest rate of growth, encompassing height, weight, body tissues, and bodily systems, since birth. Notably, the disparity in size between boys and girls remains negligible during both early and later childhood stages. However, a pivotal distinction surfaces toward the end of later childhood, with girls entering puberty earlier than boys. Girls typically complete their later childhood phase around the age of 10, while for boys, this phase concludes at approximately 12 years of age.

Termed the “skill-hungry years,” the period spanning from 7 years of age to puberty emerges in the wake of the rapid growth experienced in early childhood. Generally, boys tend to exhibit a more pronounced growth spurt during this phase compared to girls, although considerable individual variation persists.

Table 3 Movement Skills in Early Childhood

Table 3 Movement Skills in Early Childhood

Upon completion of the adolescent growth spurt, men tend to be, on average, taller and heavier than women, a trend observed across various societies and ethnicities. This disparity in final height and weight between males and females primarily stems from two key factors: the delayed onset of puberty in boys and the more pronounced intensity of the growth spurt in boys. As a result, the average adult stature of women typically hovers around 90% of men’s stature.

Adolescence represents the phase when sexual maturation becomes evident, marked by visible signs such as a sudden increase in pubic hair density. In girls, it also includes the development of the breast bud. Other significant events during adolescence encompass the production of viable sperm in boys and egg cells in girls. However, these signs do not signify full sexual maturity. This is particularly true for girls, as the first menstrual period, or menarche, is often followed by a period of sterility. On average, girls do not reach fertility until around 14 years of age or later. It commonly takes an additional 4 years before achieving full sexual maturity.

For adolescents, this period represents a time of relative stability. During this phase, they can expand their physical competence in various contexts. Having already acquired fundamental movement skills, children now enhance their abilities in new and challenging situations. They achieve this by refining, combining, and elaborating on their fundamental movement skills, enabling them to perform more specialized actions, including sports, dance, and games, often conforming to social stereotypes.

Adolescence

The transition to adolescence is characterized by a notable surge in the growth velocity of nearly all body parts, although these different body components reach their peak growth rates at varying times. This accelerated phase of growth, known as the adolescent growth spurt, signifies a pivotal developmental stage. It’s during adolescence that secondary sexual characteristics make their appearance. These changes encompass transformations in the external genitalia and differences in body size and composition.

Adulthood and Senescence

The transition from adolescence to adulthood is marked by two significant events: the cessation of height increases and attaining full reproductive maturity. Adulthood is typically a period of relative stability in terms of physical growth. While muscle mass can increase with regular weight-bearing physical activity and body fat can decrease with low-intensity exercise, overeating tends to raise body fat levels. Nonetheless, compared to the dynamic growth phases earlier in life, adulthood is characterized by its stability.

The timing of reaching adult height varies across different populations. Western individuals from higher socioeconomic groups tend to achieve adult height around 20 years for men and 18 years for women. In contrast, other populations may experience growth for a few more years, especially if they have faced challenges like undernutrition. However, they rarely reach the final stature of their healthier, often more privileged counterparts.

Aging, or senescence, is marked by a gradual decline in an individual’s reproductive capacity and ability to adapt to stressors. The onset and nature of senescence vary widely among individuals. Some common features of aging include reduced skin elasticity, diminished mobility, and, in women, menopause, which typically occurs between ages 45 and 55. However, certain age-related conditions like cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and arthritis can be more specific to certain cultures and are often associated with Western lifestyles.

Measuring Growth

The study of physical growth has evolved over time, primarily employing two fundamental research approaches: cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. In cross-sectional studies, individuals are measured once, typically with a large number of participants at various chronological ages, and average measurements are calculated. In contrast, longitudinal studies involve taking repeated measurements of individuals over several years. Longitudinal research is more time-consuming and often necessitates a limited sample size, which contributes to the relatively diverse range of longitudinal growth studies.

Recent advancements have introduced numerous tools for measuring physical growth. While some of these tools involve the use of complex specialized equipment, many growth studies continue to employ methods that are straightforward to understand and replicate.

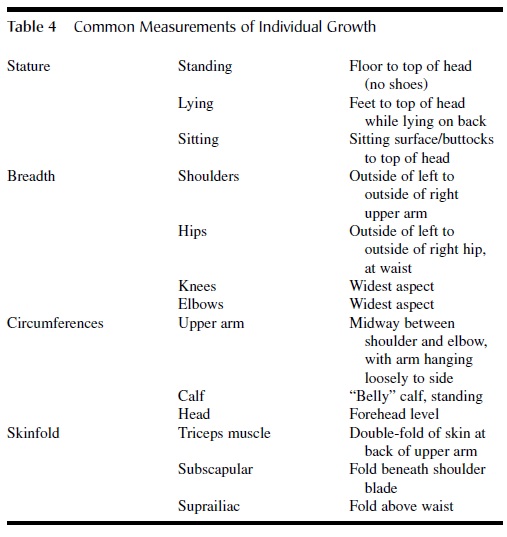

The potential measurements that can be taken of the human body are vast, but several well-established techniques have been developed. Here are some common methods used to assess physical growth, outlined in Table 4:

- Height and Length: Measuring an individual’s stature, often using a stadiometer for height and a length board for infants.

- Weight: Determining an individual’s mass with scales or balances.

- Body Mass Index (BMI): Calculating an individual’s BMI by dividing weight (in kilograms) by height (in meters squared), which provides insights into weight relative to height.

- Skinfold Thickness: Using skinfold calipers to measure the thickness of skinfolds at various body sites, which is indicative of subcutaneous fat.

- Circumference Measurements: Measuring the circumference of body parts such as the waist, hips, and limbs to assess muscle development and fat distribution.

- Dietary Assessment: Evaluating an individual’s dietary intake to understand the nutritional factors influencing growth.

- Bone Age: Assessing skeletal development through X-rays to determine an individual’s biological age.

These methods, among others, contribute to our understanding of physical growth and its various factors, such as nutrition, genetics, and environmental influences. They help researchers and healthcare professionals monitor growth patterns and identify potential issues related to development.

Regulation Of Physical Growth

Physical growth is a multifaceted process influenced by a delicate interplay of genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors. Genes provide a genetic blueprint for potential size and shape, while the environment plays a pivotal role in determining where an individual falls within that genetic range.

Genes themselves do not directly govern growth but instead produce proteins that regulate growth patterns. This regulation occurs through the intricate coordination of the endocrine and neurological systems. The endocrine system, under neural control, orchestrates the release of regulatory chemicals, creating a biochemical environment where genes exert their influence. For instance, the adolescent growth spurt hinges on the release of specific growth and sex hormones into the bloodstream. Harmful environmental factors can disrupt this delicate balance, leading to a reduction in hormone production and, consequently, stunted growth. In this way, the endocrine system acts as a mediator between genetic predisposition and environmental influences.

While genes and the endocrine system wield considerable sway over physical growth, external environmental factors—those external to the organism—also contribute to individual differences. Unfavorable environmental conditions, such as inadequate nutrition, adverse psychological and social experiences, and exposure to pollutants, can negatively impact growth, starting from the early stages of life and persisting throughout an individual’s lifespan.

The severity, duration, and timing of these harmful environmental influences determine their effects on growth. Young children are particularly susceptible to such insults. However, when the insult is removed, and proper nutrition is restored, there is often a period of catch-up growth, during which the individual rapidly approaches a normal growth rate. An apt analogy for this phenomenon is likening physical growth to a ball rolling down a valley. An insult may temporarily knock the ball off its central path, slowing its velocity. Once the insult is rectified, the ball accelerates back toward the valley floor, resuming its normal pace. However, if the insult persists, perhaps due to ongoing malnutrition, the individual’s growth may continue at a slower rate, potentially delaying skeletal maturation and extending the growth period.

The long-term effects of harmful environmental conditions during infancy and childhood are still subject to debate among scholars. While severe challenges can lead to enduring negative consequences, most cases involve temporary growth slowdowns that await improved conditions to rebound.

Environmental factors rarely act in isolation, making it challenging to pinpoint the precise relationship between specific influences and physical growth. Nevertheless, certain factors have well-documented effects on growth, including nutrition, social and environmental circumstances, psychological stress, and exposure to pollutants. Understanding these influences is crucial for promoting optimal growth and development in individuals of all ages.

Table 4 Common Measurements of Individual Growth

The effects of inadequate nutrition cast a shadow across various stages of development, but some critical periods stand out as particularly sensitive to malnutrition. In essence, the early stages of life and adolescence represent crucial junctures where nutritional deficiencies can exert lasting and profound impacts.

Prenatal Growth:

Malnutrition during prenatal growth can set the stage for health issues in the future. Proper nutrition during pregnancy is vital for the development of the growing fetus. Inadequate nourishment during this period can lead to growth abnormalities, developmental delays, and long-term health problems for the child.

Infancy and Early Childhood:

The first few years of life, often referred to as infancy and early childhood, mark a period of remarkable sensitivity to malnutrition. This heightened sensitivity is partly due to the rapid pace of growth during these years. Global studies indicate that roughly half of all deaths within the first five years of life can be attributed to poor nutrition and the associated compromised immune function. Nutritional deficits during this period can stunt growth, impair cognitive development, and increase susceptibility to infectious diseases.

Adolescence:

Adolescence is another critical phase where individuals are particularly vulnerable to the effects of malnutrition. Nutritional requirements are exceptionally high during this stage, surpassing the needs of any other life period. Although the rate of proportional growth is not as rapid as during infancy, it persists for a more extended period. Adolescents often experiment with their dietary choices, and inappropriate decisions can have far-reaching consequences.

Conditions such as anorexia nervosa, characterized by an irrational fear of becoming obese, and bulimia nervosa, involving binge eating followed by guilt-driven fasting, are especially prevalent among adolescent girls. These disorders not only threaten overall health but also jeopardize physical growth. Furthermore, inadequate nutrition during this time can negatively impact skeletal development. There is evidence linking insufficient food intake with the development of osteoporosis, a condition characterized by brittle bones, particularly in women.

In summary, the effects of poor nutrition span a lifetime, with particular vulnerability during the early years of life and adolescence. Nutritional deficits during these sensitive periods can impede physical growth, cognitive development, and overall health, emphasizing the critical importance of proper nutrition throughout all stages of life.

Nutrition

Nutrition is the cornerstone of physical growth and development. A decrease in the growth rate is one of the initial responses to insufficient food intake. In regions where food scarcity persists, children frequently experience growth delays, resulting in shorter and lighter stature compared to those in regions with abundant food supplies. The relationship between growth and nutrition is so profound that the measurement of physical growth is widely employed as an indicator of a child’s nutritional status.

Social and Economic Status

Children from lower-income families tend to exhibit shorter stature and lower weight than their peers from higher-income households. This discrepancy can be attributed in part to differences in food consumption. Interestingly, social and economic factors seem to impact the timing of growth rather than its magnitude. For instance, puberty often commences earlier in individuals from more affluent backgrounds. While studies on preschoolers have reported variations in height, weight, skin-fold thickness, and musculature in favor of children from higher social and economic status families, much of these differences tend to diminish or disappear by adulthood. It’s noteworthy that social and economic influences predominantly affect males, and the underlying reasons for these gender-specific variations remain unclear.

Psychological Stress

Extensive evidence indicates that severe stress can hinder physical growth and development. The precise mechanisms responsible for these effects remain elusive, although stress might adversely affect the secretion of growth hormones. A multitude of factors, including maternal care, social isolation, parental substance abuse, and sexual abuse, are associated with psychological and emotional distress, potentially impacting growth. Recent research has also uncovered a genetic predisposition to stress, wherein some children respond to stress in an extreme and prolonged manner, leading to restricted growth.

Pollutants

Physical growth is sensitive to various pollutants, such as lead, air pollution, specific organic compounds, and tobacco smoke. While pollutants are pervasive in modern society, the degree of exposure varies widely among different groups, leading to disparate effects. For example, maternal smoking during pregnancy is known to affect birth weight and subsequent infant growth. Moreover, residing in a household with smoking parents has been linked to reduced height and weight during infancy and childhood. Although the weight deficit often normalizes as individuals approach adolescence, the deficit in height typically persists.

Conclusion

Physical growth is fundamentally a biological process, intricately intertwined with the environments in which it unfolds. This complex interplay between biological and environmental factors not only accounts for the substantial variability in growth observed among individuals but also shapes the development of other physical characteristics, including the acquisition of movement skills.

Growth is a pivotal yet occasionally overlooked dimension of human development. Its significance is most pronounced during infancy and childhood, during which physical transformations usher in a diverse array of new behaviors and experiences. Physical growth and development profoundly influence an individual’s self-perception and how they are perceived by others. Furthermore, growth serves as a visible indicator of an individual’s overall developmental stage and their state of health and well-being. Consequently, it demands attention from anyone with a vested interest in comprehending the intricacies of human development.

References:

- Bogin, (1999). Patterns of human growth (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Brook, G. D. (2001). Clinical paediatric endocrinology (4th ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prev (2000). Growth charts: United States. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/

- Cogill, B. (2003). Anthropometric indicators measurement guide (Rev. ). Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development. Available from http://www.fantaproject.org/ publications/anthropom.shtml

- Doherty, J., & Bailey, R. P. (2003). Supporting physical development in the early years. Buckingham, UK: Open University

- Eveleth, P. , & Tanner, J. M. (1990). Worldwide variation in human growth (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Lohman, T. , Roche, A. F., & Martorell, R. (1988). Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Malina, R., & Bouchard, C. (1991). Growth, maturation and physical activity. Champaign, IL: Human

- Tanner, M. (1988). History of the study of human growth. New York: Academic Press.

- Tanner, M. (1989). Foetus into man (Revised & enlarged). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.