Organ transplantation is an accepted therapeutic option for end-stage diseases of the kidneys, heart, liver, and lungs. Other forms of transplantation, including stem cell transplantation for diseases of the blood and intestinal transplantation for severe gastrointestinal disorders, are also becoming viable alternatives for extending and improving the quality of patients’ lives. Thousands of persons receive the “gift of life” each year, and the majority are able to resume a lifestyle that was no longer possible with their end-stage disease. The new organs may extend their lives by years or even decades.

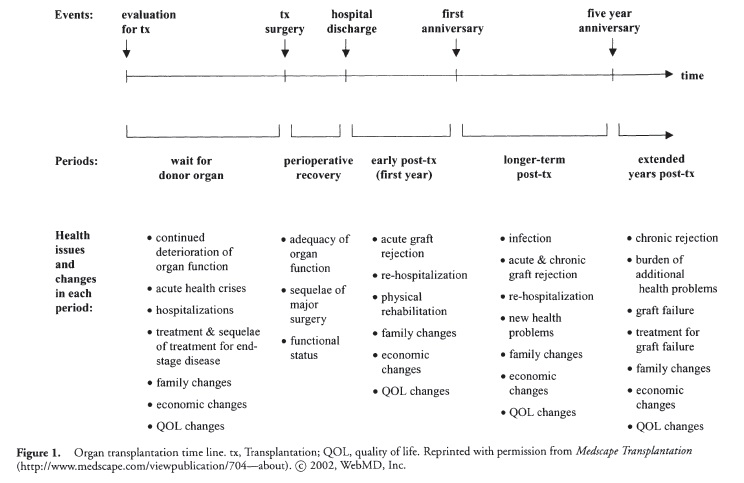

As for all medical therapies, there are psychological and health-related costs and benefits associated with transplantation, both for the organ recipients and for their families. Many of these costs and benefits are linked to specific phases of the transplantation process: Organ transplantation is best considered not as a discrete event (i.e., the surgery itself), but as a series of events and time periods that are associated with unique stressors and demand specific coping strategies. Figure 1 illustrates the typical time line for most individuals, whose initial contact and evaluation by the transplant medical team marks the beginning of the process of waiting for an organ, undergoing the surgery and initial postsurgical recovery period, returning home for the first year of rehabilitation after the transplant, and coping with new health challenges during the extended years after the surgery. Although some elements of the process can vary considerably in their duration (e.g., the length of the waiting period before transplant), the basic ordering of events and time periods is similar for all patients and all types of organ transplants. This article discusses the key issues facing patients and their families during these events and time periods.

The Initial Evaluation for Organ Transplant

The formal medical evaluation for transplant candidacy is usually the first occasion during which patients and their families seriously consider transplantation as a therapeutic option. The evaluation may evoke conflicting feelings, including relief and the hope of having a healthy future, fears about surgical risks and adapting to life with “someone else’s” organ, anxiety about whether the patient will be judged to be a suitable candidate, and realistic concerns that an organ will not become available soon enough to save the patient’s life. Patients’ heightened psychological distress related to these issues and their deteriorating physical health may significantly increase the perceived stressfulness of the medical evaluation.

The evaluation is usually lengthy and complex because it is designed to assess all aspects of patients’ clinical and psychosocial status. In addition to biomedical and laboratory tests, mental health and substance use history, cognitive status, history of compliance with medical treatments for the disease, available social supports, and coping styles are routinely assessed because these factors may influence patients’ psychological adaptation to waiting for the transplant and to life after the transplant. These psychosocial elements of the medical evaluation often serve as important additional stressors to patients and families because the information obtained may be used to decide whether patients should be immediately listed as transplant candidates or whether they need to undergo additional interventions to improve their health status and adherence to the medical requirements set by the transplant team. For example, they may need to enroll in alcohol or smoking cessation programs before they can be accepted onto the waiting list.

The Waiting Period

Many patients and their families perceive the waiting period to be the most psychologically stressful part of the transplant experience, due in large part to the patients’ continued physical health deterioration and the inherent uncertainties about whether and when a suitable donor organ will become available. Like many chronic disease populations, transplant candidates are at high risk for psychological distress and depressive and anxiety-related disorders. Transplant candidates’ cognitive status is often impaired as well. For example, hepatic encephalopathy is common in liver candidates. Heart transplant candidates often show cognitive deficits due to reduced blood flow to the brain. Kidney candidates who are not well dialyzed may have a range of subtle cognitive deficits. Continued elevations in psychological distress and/or mental status changes may lead patients to have difficulty adhering to the healthy lifestyle and medical regimen requirements set by the transplant team. For example, it may become difficult to follow specific diets or refrain from smoking or drinking.

As their organ function declines, patients may require increasingly complicated medical technologies and treatment regimens. These treatments themselves serve as stressors for patients. The strain may extend to the family as well. The patient’s marriage and relationships with primary family caregivers (who are most often spouses of adult patients and parents of pediatric patients) are particularly vulnerable due to role changes within the family and changes in daily living activities and schedules.

The Surgery and the Perioperative Recovery Period

This phase of the transplant process is characterized by major, but often positive, physical and emotional transitions. With the surgery completed, a majority of patients and their families are optimistic about prospects for recovery. The central concerns for most patients and families usually involve how well the new organ is functioning and the probable speed of the patient’s physical recovery. These concerns are sometimes heightened by knowledge that, due in part to health insurance coverage limitations, hospital stays following the surgery are brief, ranging from 1 week to several weeks in the absence of major complications.

Moreover, the brief posttransplant hospital stay is often perceived as stressful because patients and families typically receive many educational materials about life posttransplant during this time. (This information may have been provided before the transplant as well, but it is likely to have been difficult for patients to absorb due to other stresses and/or cognitive impairment during the waiting period.) The positive feelings and optimism that often dominate after the surgery can interfere with educational efforts during the perioperative period because these feelings may lead patients and their families to be less able to accept and focus on information concerning potential complications, financial issues, and family difficulties that can arise posttransplant.

The First Year after the Transplant

For most transplant recipients, the first year after the surgery brings gradual improvements in all domains of quality of life, including physical functional status, emotional well-being, and social functioning. Many important psychosocial issues, however, may slow patients’ improvement and may also affect family members’ well-being. These issues are related to patients’ need to (1) cope with physical and emotional changes induced by the immunosuppressive medications required to prevent organ rejection, (2) alter their self-image beyond that of a critically ill individual and resume a less illness-focused lifestyle, (3) psychologically accept the transplant and the fact that, in cadaver donation, donors lost their lives just when recipients regained theirs, and (4) manage the continuing financial costs associated with the transplant and follow-up care.

A likely result of these concerns is that risks of experiencing emotional distress and clinically significant episodes of depressive and anxiety-related disorders are higher during the first year posttransplant than during later years. Some psychiatric disorders, for example, posttraumatic stress disorder related to the transplant, may be limited almost exclusively to the first year.

An additional area of difficulty for many patients is compliance with their complex posttransplant treatment regimen. Not only must patients take multiple medications, but they have exercise and diet requirements, follow-up medical evaluations and laboratory tests, and restrictions on smoking, alcohol, and other substance use. Compliance in most areas of these areas worsens over the first year after the transplant, just as it does for most patients with complex regimens. Psychosocial and emotional strains during the year exacerbate patients’ risk of having difficulty with the medical regimen.

The Extended Years after the Transplant

Compared to the other phases of the transplant experience, less is known about psychosocial and adjustment issues that arise in the long term posttransplant. This is due largely to the fact that, with the exception of kidney transplantation, long-term survival in solid organ transplantation (heart, liver, lung) has only become a reality in recent years. Nevertheless, as shown in Figure 1, the years beyond the first anniversary of the transplant can be divided into at least two periods. There is usually a multiyear period following the first anniversary in which patients achieve maximal functioning of the transplanted organ, with a relatively low level and severity of complications and infrequent episodes of acute organ rejection. Patients’ physical functional capabilities and quality of life are often high. With time, however, other problems with the organ often develop (e.g., “chronic” rejection), and patients may become more limited functionally due to long-term immunosuppressive medication complications, including diabetes, hypertension, and cancer.

Many of the psychosocial and health-related concerns that emerged during the first year posttransplant carry over into subsequent years. Focal issues for patients in the long term concern maintaining as high a quality of life as possible and postponing the effects of declining organ function and related complications. Financial strains related to continuing medication and health care needs may assume greater prominence. These sources of stress may provoke renewed increases in distress and rates of psychiatric disorders in over the very long term.

Conclusion

Each phase of the organ transplant process, from the initial evaluation through the long-term years after the transplant, is associated with unique stressors and psychosocial issues that are of concern to both patients and their families. Patients’ physical and mental health at one phase of the process are affected by, and in turn affect, their health in other phases. Moreover, the transplant experience influences the well-being of the patient’s family. Identification of the unique difficulties and concerns experienced by patients and families during this process will allow for the development of interventions to reduce the impact of these difficulties on individuals’ health.

References:

- Cupples, S. A., & Ohler, L. (Eds). (2002). Solid organ transplantation: A handbook for primary health care providers. New York: Springer.

- Dew, M. A., Manzetti, J., Goycoolea, J. M., Lee, A., Zomak, R., Vensak, J. L., et al. (2002). Psychosocial aspects of transplantation. In S. L. Smith & Linda Ohler (Eds.), Organ transplantation: Concepts, issues, practice and outcomes (Chapter 8). New York: Medscape Transplantation.

- Trzepacz, P., & DiMartini, A. (2000). The transplant patient: Biological, psychiatric and ethical issues in organ transplantation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Back to Health Psychology.