Despite inconsistencies and ambiguities associated with the concepts of stress and coping, the popular press regularly discusses the ill effects of stress on physical and psychological well-being and a variety of behavioral antidotes, including aroma therapy, biofeedback, and meditation. Although the possible adverse effects of stress have been noted for thousands of years, the scientific study of stress and coping did not burgeon until after World War II. Indeed, a body of research suggests that the technological developments of our modern life are a double-edged sword. On one hand, technological and industrial advances (e.g., improved sanitation, housing, and medical care) reduced infectious diseases and trauma, the chief causes of death prior to 1900; on the other hand, other developments fostered diseases of lifestyle (e.g., heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and some cancers) associated with the transition from a hunter-gatherer society to our modern Western age of industrialization and technology. Unhealthy aspects of the Western lifestyle include poor nutrition, pollution, lack of exercise, increased substance abuse, loss of social support from an extended family and community, and a chronic sense of “hurry-worry” triggered by the demands of a fast-paced society. That is, the disease-producing features of our modern ways appear linked to behavioral and psychological processes that are discordant with the Stone Age biology we inherited during the evolution of our species.

In the 1970s, a cardiologist affiliated with Harvard Medical School, Dr. Herbert Benson, synthesized scientific evidence with ancient Eastern and Western writings in the formulation of an innate human ability he termed the relaxation response. The relaxation response is innate in that it is grounded in our evolution. Since this time, Benson has published research and written extensively on the daily use of the relaxation response as a component of a lifestyle designed to counter the unhealthy aspects of modern life.

Following a brief introduction to the structure of the nervous system, this article discusses the fight-or-flight response and the relaxation response, and compares the two. The elicitation the relaxation response is then described, including a simple method to use. Other methods that can elicit the relaxation response and evidence of their salubrious effects are also presented. The article closes with future directions and implications.

Stress, Restoration, and the Nervous System

The central nervous system (CNS) is composed of the brain and the spinal cord, both encased in bone. Many unconscious and voluntary bodily responses are regulated by the CNS; this regulation is based on information, emanating from both inside and outside the body, transmitted to and from the CNS via peripheral nerves not encased in bone (namely, the peripheral nervous system, PNS). A subdivision of the PNS, namely, the autonomic nervous system (ANS), contains nerve fibers designed to regulate internal organs and glands for the purpose of homeostasis, an internal physiological balance conducive to the maintenance of life. Hence, the ANS is constantly working at striking a balance between energy conservation (rest and restoration) and energy expenditure (physiological adaptations for exercise, and attack or defensive maneuvers). Rest and restoration are the domain of the parasympathic nervous system (PSNS) and are linked to the relaxation response, whereas adaptation to states of physical exertion, threat, and emergency are the domain of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which is linked to the fight-or-flight response. The brains registering of threatening or crisis situations triggers the SNS and reduces PSNS activity, and sets in motion a cascade of events inducing the release of stress hormones (bodily created substances released into the bloodstream for regulation of the body’s responses).

A Comparison of Two Innate Responses

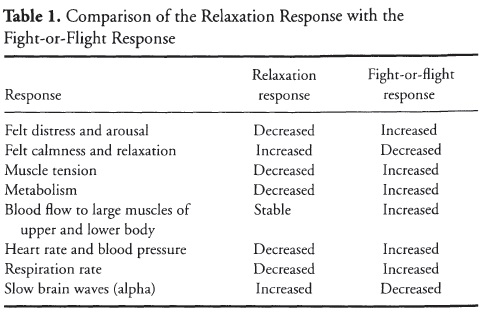

Table 1, based on Benson’s conceptualization, shows the physiological differences between the fight-or-flight response and the relaxation response. Because the fight-or-flight response is for adaptation to threat, blood flow is channeled to the brain, heart, and muscles of the legs and arms and away from the viscera and skin (hence, one has cold hands when stressed). Activation of the SNS, release of stress hormones, and increased respiration and cardiovascular system activity move oxygen and nutrients liberated from bodily stores to large muscles and the brain; this response is quickly activated for a vigilant mental state and the behavioral and affective responses of fighting or fleeing. These physiological reactions mark an increase in metabolism induced by environmental exigencies (e.g., jogging or being attacked by a bear); metabolism basically is the process whereby oxygen is consumed or burned for the generation of energy necessary for the body’s functioning. Although this Stone Age response system is metabolically appropriate for running from or fighting a bear, it represents a set of responses in excess of metabolic demand for many modern stressors (i.e., events or objects, whether actual or imagined, that trigger stress). In contrast to the stressors of hunting or defending against attacking animals, our modern stressors are mostly symbolic in nature (e.g., reacting to a playful joke as an injurious insult). It is thought that a frequent or chronic triggering of the fight-or-flight response across life can contribute to bodily changes that pose a risk for such diseases as coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and some cancers. As indicated, diseases involving psychosocial stress appear to result, in part, from the mismatch between the modern way of life and our primordial stress reactivity.

As shown in Table 1, Benson characterizes the relaxation response, with its decreased respiration, muscle tension, and cardiovascular activation, as a hypometabolic state characterized by a quieting and calming of both the mind and the body. It is linked to the PSNS and, thus, rest and restoration.

According to Benson, regular use of the relaxation response helps to counter negative mental states (e.g., anxiety, tension, irritability, and depression) and the damaging aspects of the fight-or-flight response. That is, excessive use of the quick-acting, SNS-driven fight-or-flight response is counterbalanced by the less quickly elicited relaxation response of the PSNS. In essence, regular elicitation of this hypometabolic state of relaxation is thought to aid in tuning out daily worries, stresses, and strains while contributing to the body’s needed rest and restoration by augmenting PSNS activation and diminishing SNS activation.

Elicitation of the Relaxation Response

In the course of his systematic and extensive study of Eastern and Western forms of meditation, Benson formulated four components related to bringing forth the relaxation response.

First, a quiet place without distractions is necessary. This place can be a room in one’s home, a place of worship, or even a distraction-free area at work. Again, the key feature of a good relaxation context is a quiet place where one feels safe, calm, and free from distracting sights and sounds. Distracting sights and sounds can evoke negative affective states (e.g., irritation and frustration) and vigilance, both of which are associated with SNS activation. In essence, the place must be conducive to an effortless or easy direction of awareness to events or stimuli generated within oneself.

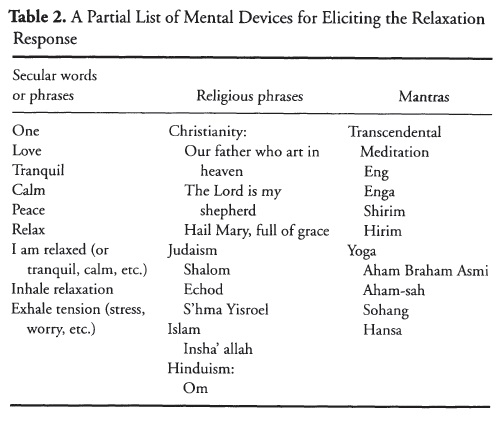

Second, a “mental device” or ongoing stimulus is used to orient the individual inwardly and away from logical and vigilant thought. This device can be a sound, a phrase, or a word repeatedly silently or aloud with eyes closed; it also can be a passive fixing of one’s eyes on an object, a slow, repetitive series of movements as in Tai Chi Chuan, or pondering a Zen koan (unsolvable riddle). A passive attending to one’s breathing can aid in use of the mental device and turning one’s attention inward. Some examples of mental devices are presented in Table 2.

Third, cultivation of a passive or nonjudgmental attitude is crucial to elicitation of the relaxation response. Distracting thoughts and feelings will occur. One should easily favor the sound (e.g., repetition of a Sanskrit word or mantra), phrase, awareness of breathing, gazing at an object, or whatever is chosen as the mental device. One should simply notice the distracting thoughts, feelings, or both, and then easily restart the mental device without judging the distractions, the momentary disruption of the use of the mental device, or the level of relaxation. The elicitation of the relaxation response is designed to give a break from the stress of comparisons and judgments imposed by oneself and others. It is important not to judge one’s relaxation!

Rather, it should simply be experienced for what it is, whether it be deep or light, or a letting go of many or few mental and affective states. Depth of relaxation will vary within and across periods of elicitation of the relaxation response, which is alright. Relaxation cannot be willed, only permitted to happen in a permissive, passive state of awareness.

Finally, a comfortable position is important as a means of avoiding undue muscular tension, which can serve as a distracter or contribute to SNS activity. Some people sit with legs crossed (e.g., using the lotus position of a yogi); cross-legged or kneeling positions are designed to keep the practitioner from falling asleep. Hence, lying down, although comfortable, is not suggested due to the tendency to fall asleep rather than to bring forth a wakeful hypometabolic state.

The following is a procedural outline for eliciting the relaxation response:

- Sit comfortably in a quiet place. You may place your hands in your lap.

- Close your eyes and simply notice your inhalations and exhalations.

- Relax muscles, starting with the feet and moving up to the head. Sink or settle into the furniture or floor.

- As you slowly breath in and out of your nose, think the word “one” during exhalation (i.e., breath in … breath out, think “one”). As stated before, phrases can be used. For example, think “I am” as you slowly inhale, and then think “relaxed” as you slowly exhale.

- Continue the process for 10-20 min. Feel free to shift your body for comfort, look at your watch to check on time, scratch, and so forth. Once the relaxation period is over, sit quietly for several minutes, at first with eyes closed, prior to standing up.

- As discussed earlier, maintain a passive attitude toward your experience.

Other Methods Deploying the Relaxation Response

Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR), guided imagery, autogenic training, and hypnosis have been deployed to manage stress. During the initial stages of learning, a therapist teaches the client the procedures, which are followed by practice outside the treatment context. All of these techniques share the features necessary to induce the relaxation response. PMR involves closing the eyes, passively attending to verbal instructions to tense and relax large muscle groups (e.g., lower leg, upper leg, forearms, biceps, torso, and shoulders), to feelings characteristic of relaxation (warmth, heaviness, and tingling sensations), to suggestions of letting go of tension, and, in many instances, to imaging of serene contexts. An extension of PMR, cue-controlled relaxation, involves associating a word cue (e.g., “calm” or “relaxed”) as one exhales while in a deep state of PMR-induced relaxation. The objective is to condition the cue word to elicit relaxation before, during, and after states of stress. For decades, PMR has been integrated into the behavior therapy of phobias, fear, and generalized anxiety. Over the years, stress management procedures using PMR have been reported to be effective in the behavioral treatment of a number of health-related conditions (e.g., hypertension, coronary disease-prone behavior, reduction of the side effects of chemotherapy in cancer patients, pain, and insomnia).

It is typical for a technique to share a number of features with other techniques. Like PMR, hypnosis, guided imagery, and autogenic training all involve therapist verbalization of suggestions/instructions as the client is in a comfortable position (e.g., recumbent in recliner) with eyes closed. A comparison of these techniques reveals that all share the components necessary for elicitation of the relaxation response. First, all involve a quiet, safe environment. Second, all involve a mental device as a means of orienting away from active perceptions and transactions with ongoing environmental changes: Guided imagery can involve the mental revivification of a tranquil place (e.g., sitting in a forest looking at the sun streaming through the trees); hypnosis can start with fixation on an object (e.g., a watch) until the eyes close, followed by attending to internal physical sensations, images, and thoughts suggested by the hypnotist; autogenic training typically involves covert repetition of phrases (e.g., “My right arm is warm and heavy”); therapists using PMR will suggest sensations connected to relaxation as clients attend inwardly to the tensing and relaxing of muscle groups. Finally, these techniques usually encourage a nonjudgmental/passive attitude to foster relaxation and receptiveness to suggestion while clients are comfortably positioned.

Research Evidence

For quite some time, the effects of interventions containing a relaxation component or focusing just on relaxation have been investigated in relation to high blood pressure, rehabilitation following a heart attack, insomnia, anxiety disorders, reduction of the side effects of chemotherapy for cancer, tension headaches, and pain. Although salubrious effects have been reported for this partial list of disorders, there are a number of unanswered questions. The results of meta-analytic reviews will now be reviewed. In meta-analysis, statistics used to test differences between groups (e.g., persons taught relaxation vs. those who were not taught) are combined across research studies to yield an average statistic showing the strength or magnitude of the treatment effect.

In the treatment of panic disorder (intense, disabling states of anxiety, as in fear of open spaces), treatment packages focusing on coping strategies, relaxation training, cognitive restructuring (changing ones view and interpretation of things), and exposure (use of imagery and actual behavior to approach the feared context) provided the most consistent positive results. Behavioral assessment showed less of an effect than other assessments (e.g., physiological and self-report), and the biggest effects were obtained for comparisons of treatment with a drug placebo. All in all, meta-analyses show that exposure is required to effectively treat panic and agoraphobia (fear of open spaces). Trait anxiety, or the general tendency to experience signs of anxiety (e.g., physical symptoms such as rapid heart rate and sweaty hands, as well as such mental states as worry, tension, and low self-worth) across situations, also has been examined. Interestingly, Transcendental Meditation, which utilizes repetition of a Sanskrit mantra, displayed the strongest effect of all the relaxation techniques. Moreover, concentration meditation (i.e., focusing on an external object like a vase) showed the weakest effect in the treatment of trait anxiety.

Chronic sleep disturbance, or insomnia, is a frequent health complaint. Relaxation techniques targeting cognitive arousal (intrusive thoughts, racing mind) were slightly superior to those focusing of physiological arousal (muscle tension); attention-focusing techniques like meditation and imagery training were categorized as targeting cognitive arousal, whereas biofeedback, PMR, and autogenic training were categorized as focusing on somatic arousal. Relaxation training also has been deployed as a component of rehabilitation programs for people with heart disease and high blood pressure. Regarding rehabilitation programs for heart disease, the total package appears to have a favorable impact on mortality and factors, such as decreased blood pressure, decreased smoking, and increased exercise, linked to increased risk of death. However, it is unclear whether relaxation training contributes to treatment effectiveness above that obtained from interventions designed to increase awareness of risk factor modification and deployment of behavioral strategies for risk factor modification. High blood pressure, a disease thought to be stress related in some cases, has been treated with interventions by meditation, PMR, and stress management packages using relaxation and interventions designed to alter the way people think about stressful circumstances. In general, relaxation has been associated with reduction of high blood pressure. However, the best results are linked to tailoring the stress management to the stresses and strains of the individual. For example, some people may deploy relaxation to help manage frequent daily bouts of anger, whereas others may deploy relaxation to aid in the management of daily bouts of social anxiety.

Conclusions

The hypometabolic relaxation response is thought to counter the deleterious effects of the stress of modern times, and a large body of research supports use of relaxation in a variety of treatment contexts, including cardiac rehabilitation, high blood pressure, insomnia, and anxiety disorders. A daily elicitation of the rest and restoration of the PSNS is believed to be the mechanism underlying the health-fostering effects of the relaxation response.

For quite some time, it has been thought and shown that people vary in the triggers, mechanisms, and physical and psychological expressions of the SNS-linked fight-or-flight response. Likewise, evidence is arising suggesting variability among people regarding the ability of the PSNS to counter excessive SNS activity; that is, some people may experience frequent anxiety and stress attacks due to a decreased capacity of the PSNS to keep excessive and unwarranted SNS activation in check. Interestingly, some people experience high anxiety while practicing relaxation, which is termed relaxation-induced anxiety (RIA). Effective stress management deploying relaxation tailors the treatment to the individual, and it is possible that RIA could be avoided in some cases by using a relaxation technique (e.g., PMR with its focus on muscle tension vs. relaxation) that does not focus on mental activity (e.g., mantra meditation), and thereby reduces the likelihood of ruminations evoking anxiety.

Despite positive advances in understanding the relaxation response, much work is necessary to fully comprehend its role in the treatment of stress-related problems. More component analyses, or isolation of the effects of individual aspects of a stress management package, are required to assess the treatment efficacy of the relaxation response relative to other factors (e.g., alteration of thinking). The relaxation response is associated with multiple factors connected to physiological, mental, and contextual (e.g., familial support for relaxation practice) dimensions that are conducive to a positive outcome. In other words, more fine-tuned research is required to understand why the relaxation response works in some cases but not in others. Does the state of the ANS (e.g., an impaired capacity for the PSNS to counter the SNS) affect relaxation induction? Can such ANS imbalance be adjusted with a relaxation intervention? Are cognitive changes (e.g., generalizing to daily living the ability to let go of stressful thoughts while meditating) necessary to maximize generalization of relaxation training to everyday stress management? Are certain people best suited for certain techniques? These and related questions await further inquiry.

References:

- Benson, H. (1976). The relaxation response. New York: Avon.

- Benson, H. (1996). Timeless healing. New York: Scribner.

- Clum, G. A., Clum, G. A., & Surls, R. (1993). A meta-analysis of treatments for panic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 317-326.

- Dusseldorp, E., van Dlderen, T., Maes, S., Meulman, J., & Kraaij, V. (1999). A meta-analysis of psychoeducational programs for coronary heart disease patients. Health Psychology, 18, 506-519.

- Eaton, S. B., Konner, M., & Shostak, M. (1988). Stone Agers in the fast lane: Chronic degenerative diseases in evolutionary perspective. American Journal of Medicine, 84, 739-749.

- Eppley, K. R., Abrams, A. I., & Shear, J. (1989). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45, 957-974.

- Jones, E, & Bright, J. (2001). Stress: Myth, theory and research. London: Pearson Educational.

- Lichstein, K. L. (1988). Clinical relaxation strategies. New York: Wiley.

- Mattick, R. P., Andrews, G., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., & Christensen, H. (1990). Treatment of panic and agoraphobia: An integrative review. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 178, 567-576.

- Morin, C. M., Culbert, J. P., & Schwartz, S. (1994). Nonpharmacological interventions for insomnia: A meta-analysis of treatment efficacy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1172-1180.

- Rice, P. L. Stress and health (3rd ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Thayer, J. R., & Lane, R. D. (2000). A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 61, 201-216.

Back to Health Psychology.